Almost exactly 60 years ago, the world held its breath.

For 13 days in October, 1962, as President John F Kennedy decided how to react as Russia deployed ballistic missiles on Cuba, 450 miles from the coast of Florida, the world stood on the brink of unthinkable conflict, on the edge of nuclear war.

When he started researching the story of the Cuban Missile Crisis, author and historian Sir Max Hastings believed he was detailing a moment when the world got lucky. He did not suspect events in Ukraine would make his analysis alarmingly, shockingly of the moment.

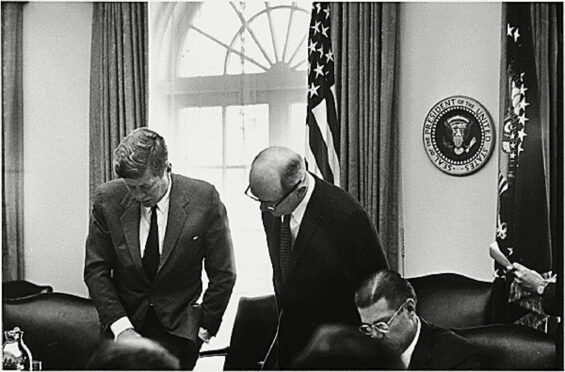

At the apex of the Cold War, Kennedy was being briefed that an American U-2 spy plane had found deployments of Soviet ballistic missiles on Cuba, placed in response to the presence of similar US weaponry in Turkey and Italy. The president was urged by his security chiefs to bomb then invade the island.

Hastings argues in his new book, Abyss, that this was the president’s finest hour as he slowed the pace and showed restraint in the face of White House hawks as he took time to carefully consider the consequences of attacking the Soviets.

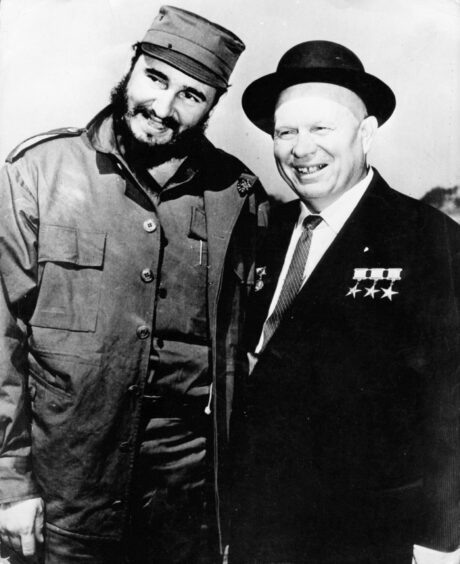

Eventually, through a carefully calibrated public response and back channel diplomacy with the Kremlin led by Nikita Khrushchev, disaster was averted and the world slowly exhaled.

Now, 60 years on, Vladimir Putin’s veiled but persistent threats of using nuclear weapons as his disastrous invasion of Ukraine grinds on means the lessons learned in 1962 are more timely than ever.

Hastings admits: “I’ve never felt so sorry to suddenly find something I’ve written so relevant. I thought I was just writing about history.

“Since the end of the Cold War, an awful lot of people have behaved and talked as if nuclear weapons have suddenly been un-invented. We’ve talked about climate change and terrorism, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and so on.

“We haven’t thought about nuclear weapons and yet suddenly, Putin has put them right back in the centre of the agenda and I think it’s enormously important to learn some lessons from 1962 in thinking about how we deal with his monstrous aggression today.”

In his book, Hastings, a respected military historian, former BBC war correspondent and national newspaper editor, tells the story of the crisis from the viewpoints of national and military leaders on all sides, ordinary Cubans, American pilots and British disarmament campaigners.

After looking back to research the book, his suspicion that we are at the start of a new Cold War has only hardened as the ideological battle of Communism versus Capitalism has been replaced with a rivalry between the world’s superpowers for dominance.

For the rest of our lifetimes and beyond, there is, according to Hastings, likely to be a struggle for power, territory, and energy between the US, Russia and China.

He said: “The late historian Michael Howard, who is the wisest man I’ve ever known, used to say that he thought the world was a more dangerous place than it had been at any time since 1945 because order and stability had been lost, and this was even back in 2019.

“What we have to hope for, and this is a lesson from the missile crisis, and indeed from the whole Cold War, is that we need calm, sensible, wise leadership, and there ain’t a lot of it about.

“I would like to think that we are not, at this moment, in quite as dangerous a situation as we were in 1962, where the Americans were within a whisker of bombing and invading Cuba, which could have provoked a general nuclear war.

“The Americans remain the ones who matter and so far they are still not even discussing the possibility of intervening directly militarily against Russia. But if Putin exploded a nuclear device, which is certainly possible, then the world would once again be in a terrifyingly dangerous place. Once you get into that cycle of escalation with nuclear armed powers, anything is possible.”

On Putin, Hastings said: “He is sitting on the largest nuclear arsenal in the world. His power to destroy us all is not in doubt. I think he’s a less stable and more isolated figure than Khrushchev. We now know that he was absolutely terrified of the idea of nuclear weapons being exploded, and the sense we get at the moment is that one’s not so sure Putin is as frightened as God knows he should be for the sake of the planet.”

On the other side, Hastings believes the US so far has been “firm and very sensible”. Joe Biden’s administration has shipped the Ukrainians vast quantities of weapons and warned the Kremlin of the consequences of going nuclear, but refrained from rattling sabres.

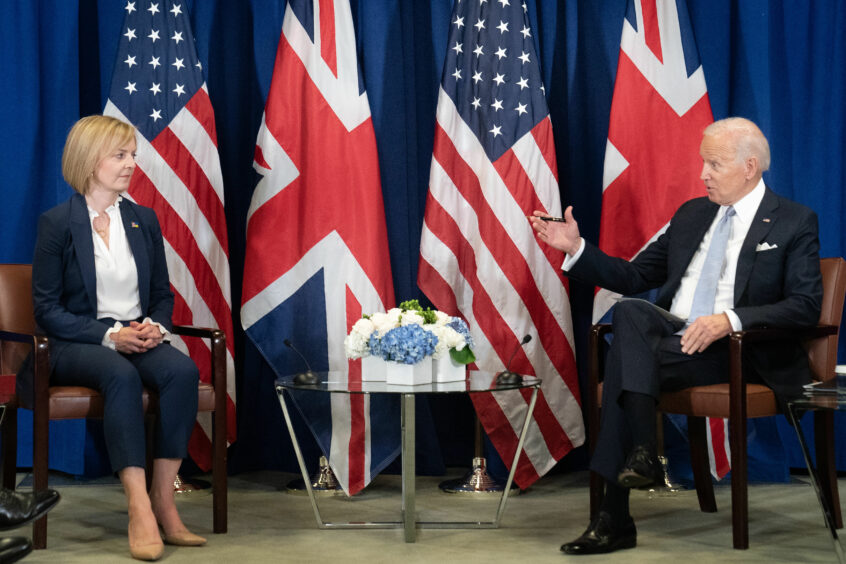

From the UK government, however, Hastings fears there has been a less tempered response, particularly from the new leader at the helm.

“The Americans’ choice of public words has been much more careful than that of some of our politicians,” Hastings said. “Liz Truss has been incredibly bellicose and has said all along that the war must go on until every last Russian is out of Crimea and the Donbas.

“I fear and suspect there will probably be some sort of dirty deal. I’m shocked by some of the people in Britain who I think should know better, who’ve been talking of the opportunity for a generational victory over Russia.

“In 1962, Kennedy saw that, instead of just trying to batter the Soviets, there was going to have to be some sort of trade, some sort of bargain. They’d have to be given something to persuade them to get their missiles out.

“You’ve got to look at what’s possible, and you’ve got to choose every word with care. Kennedy did this and I think he played a stunning hand.”

By the end of October 1962, the crisis was quelled as Kennedy publicly gave the Soviets the assurance that if they pulled missiles from Cuba, the US would never again attempt military action on the island, after the Bay of Pigs fiasco. The naval blockade put in place was ended the next month when the last Soviet missiles left Cuban soil. As part of the deal, not revealed until more than 25 years later, Kennedy also secretly gave Moscow his word that he would later withdraw American missiles from Turkey.

This level of negotiation and diplomacy, Hastings believes, would not have occurred under some of Kennedy’s successors and he believes that the comparably poor standard of leadership in 2022 is a real concern.

“I think one of the stupidest old proverbs is ‘cometh the hour cometh the man’,” he said. “It suggested that if there’s a great crisis that a wonderful leader always comes to the top of the deck. Well, history shows that isn’t so and I think that we all have cause to be very scared about the low quality of the leadership of all our countries in 2022.”

With the UK in the grip of an economic crisis, heavily impacted by the conflict in Ukraine and oil and gas being among Russia’s few remaining exports, Hastings believes there’s no “pain-free” route out of the crisis.

“A lot of leaders in democracies don’t do nearly enough to try and educate their people about what’s going on in the world and they don’t speak long and frankly enough to us about what we’re facing,” he said.

“I’d have far more respect for Truss, Johnson, Ben Wallace and so on, if from the beginning of the crisis they said we’re going to give resolute support to Ukraine but we’ve got to realise this is going to hurt us a lot too.

“Sending more billions to Ukraine is going to cost the British people. I think that cost must be borne but our governments must be honest with us. What I’ve been so saddened about by recent politics, and it’s not just in Britain but other countries, is the refusal to come clean to people about what courses of action are involved.

“It’s going to likely go on for a long time. It’s not that we’re all doomed, it’s just that I think the British people might respond better to the government if they saw them being a little bit more truthful.”

Hastings believes Truss in particular could learn from history, having been desperate to show herself as a tough leader, often resulting in her saying “reckless and stupid things”.

“This was scary when she was Foreign Secretary, but it gets much scarier when she’s Prime Minister,” he said. “I don’t think she knows much history. She wants to compare herself to Thatcher, but in many ways she was surprisingly cautious in a lot of situations. She didn’t get into big fights until she was pretty sure of winning. The first year or two of her premiership really was remarkably cautious.

“We all have good reasons to be very scared about having a prime minister such as Liz Truss.

“Boris Johnson succeeded in elevating to the British premiership one of the few people on the planet less fit to occupy the job than himself.”

Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962 by Max Hastings is published by William Collins

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © AP

© AP