The seas around the world are so littered with shipwrecks, it’s a wonder divers don’t stub their flippers on them more often.

But they are the poignant remains of vessels that lost their fight with the merciless waves.

Here, we take a look at some of the most-famous wrecks which have fallen victim to the oceans.

ROMAN WRECK IN MALTA

There are many ancient wrecks in the Mediterranean, but their stories are unknown.

About AD60 there was a shipwreck that we know about in great detail thanks to the Bible, no less.

The doctor and historian Luke was not only an eyewitness, he was on board.

The Apostle Paul was being taken from Caesarea on the coast of Palestine to Rome for trial.

In a dramatic section of Luke’s second book, Acts, he describes every measure taken by the crew of what was probably a grain ship, caught in a severe storm.

The ship was delayed and the captain found himself sailing too late in the year, a time no sane captain crossed the Mediterranean.

The ship was pulling a small dinghy and, to save it being smashed in the sea and against the stern, the crew hauled it onto the deck when the storm struck, only to plot to escape in it later. The planks of the hull were gripped by strong ropes to hold them together as the battering loosened them.

Luke writes: “We took such a violent battering from the storm that the next day, they began to throw the cargo overboard.

“On the third day, they threw the ship’s tackle overboard . . . when neither sun nor stars appeared for many days and the storm continued raging, we finally gave up all hope of being saved.”

Eventually the ship broke up on rocks near Malta. The prisoners and crew either swam to shore or were swept in on pieces of the ship. Remarkably not one of the 276 lives was lost.

The traditional site of the shipwreck is St Paul’s Island where a statue commemorates the event.

THE WHITE SHIP

“No ship ever brought so much misery to England,” wrote William of Malmesbury of the sinking of The White Ship on November 25, 1120.

King Henry I, son of William the Conqueror, had one legitimate son, William the Aethling, and Henry, his son and many nobles were returning from France after a successful campaign against the French king.

Henry was to have travelled across the Channel on The White Ship but sailed in another vessel, and his son was given the doomed ship instead.

It was filled with the royal “in-crowd”, and drink was called for, which William provided by the barrel.

By the time the party allowed the captain to set sail it was already dark.

With the bravado of the young, rich, victorious and drunk, William ordered the oarsmen to speed the vessel to catch up with his father and arrive in England before him.

In the dark, the ship hit a rock, her side was ripped open and she went under.

Not only was the heir to the throne drowned, but hardly an estate in England was untouched by grief — The White Ship had been filled with the heirs of the ruling class.

When Henry died in 1135, the tragedy of the loss of the heir to the throne precipitated The Anarchy — 18 years of civil war between two of William the Conqueror’s grandchildren, Stephen and Matilda.

Not for the first time, drink, youth and foolishness changed history.

THE MARY ROSE

Henry VIII’s great warship, the Mary Rose, sank before his eyes in the Solent on July 19, 1545.

The King was watching as his ships advanced on a French invasion fleet. Suddenly, the Mary Rose heeled over and sank rapidly, claiming at least 400 lives.

Why did she sink so quickly? There are many theories. It may have been down to human error and gun ports.

Apertures cut in the hulls of ships through which the guns could be fired were relatively new and meant the water surface was much closer to openings through which the sea could flood.

The Admiral had also complained earlier that his crew was unruly and difficult to manage.

Because of bad communication on board, the gun ports on the port side may not have been closed.

The remains of the ship were raised from the seabed in 1982, and over 19,000 artefacts have been recovered, as well as skeletons of the crew.

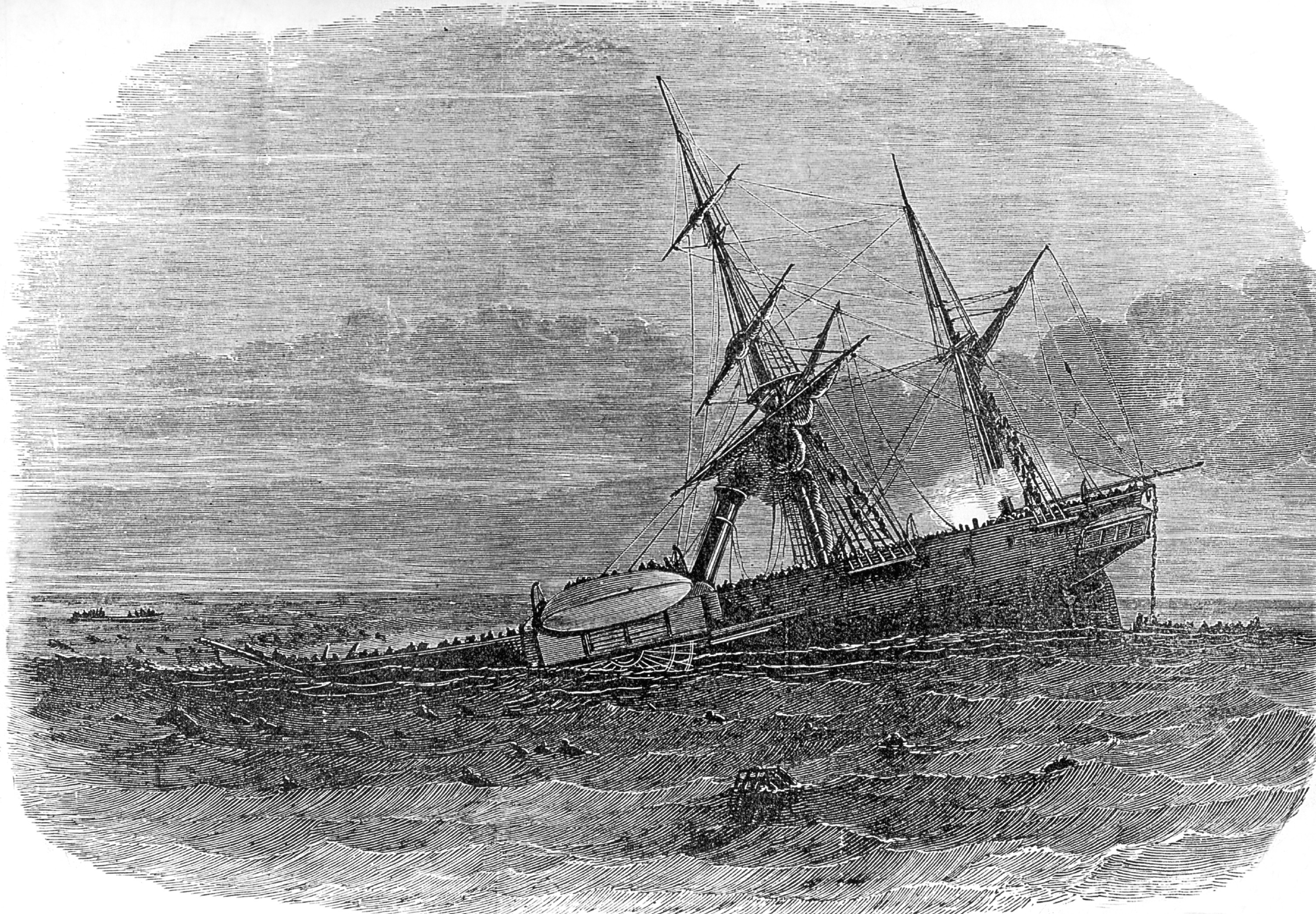

THE BIRKENHEAD

HMS BIRKENHEAD, an iron-hulled paddle steamer, is remembered not only for tragedy, but also for great bravery.

Carrying troops to fight in the war in South Africa, she sailed from Portsmouth in January, 1852.

Ireland was still suffering the aftermath of the Great Famine, and many young Irishmen joined up simply as a way of getting food and shelter.

At that time, soldiers often travelled with their wives and children and 25 women and 31 children were on board.

The Captain decided to keep close to the coast as he sailed for Port Elizabeth.

At two in the morning of January 26, everyone except the watch was asleep in calm weather.

The lookout had seen no cause for concern when suddenly the bow hit a rock.

The paddles of the ship kept turning and buckled the hull further. Water rushed in and many drowned as they slept.

The Captain ordered the engines to be put into reverse, but this action tore the ship apart even more.

Lt. Colonel Seton, the senior military officer on board, lined the troops up on deck and ordered them not to move while the women and children were put into the three serviceable lifeboats.

Even when the women and children were safe, Seton ordered the men to stay where they were as the waves swept over the deck. Seton had realised that they might try to clamber onto the escaping lifeboats and swamp them. Not a man moved.

“The Birkenhead Drill” became a byword for courage in the face of desperate odds.

This was the first time the call “Women and children first!” was made and it became the standard protocol at sea.

THE LUSITANIA

In 1915, many Americans gave little thought to the war raging in Europe. After all, what was it to do with them?

Nearly 2,000 people embarked on the Cunard liner Lusitania when it left New York for Liverpool on May 1 that year.

Ominously, the German Embassy in Washington had inserted a warning in a newspaper regarding Atlantic crossings, saying: “A zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles.”

As the ship neared the coast of Ireland, a lurking U-boat spotted her.

At 2.10 in the afternoon of May 7, the Lusitania was hit by a torpedo, fatally fracturing the hull under the waterline.

A second explosion tore it apart further and in just 18 minutes it disappeared beneath the waves. In the chaos, 1,119 people were drowned.

The tangled remains lie in just 300 feet of water.

READ MORE

How the ‘Shetland Bus’ became a wartime lifeline

Wreck of Battle of Jutland ship HMS Falmouth brought to life in 3D computer model

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe