Driven by a ramshackle punk rock ethos and a particular brand of Caledonian anarchy, it would inspire musical legends and legendary tales of bad behaviour.

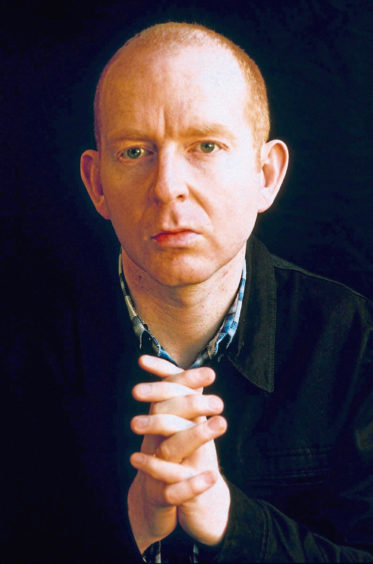

Creation Records, started by Alan McGee with a £1,000 loan and a gung-ho attitude, would deliver much of Britain’s iconic 1990s soundtrack amid a welter of breakdowns and crack-ups.

The careering highs and lows of the label behind Oasis, Primal Scream, the Jesus And Mary Chain and many more, are now being charted in a movie based on McGee’s life story to be premiered at next month’s Glasgow Film Festival.

Creation Stories is a mini-Trainspotting reunion of co-writer Irvine Welsh, executive producer Danny Boyle and star Ewen Bremner, who plays the fast-talking, hard-driving, talent-spotting McGee, who shared more characteristics than red hair with the Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren.

“Fear of failure is the reason for that inner confidence – that’s what drove me,” explained McGee.

“To fail wasn’t an option, I had to make it work. I knew I couldn’t go into any other part of life and be that successful, but I seemed to do well with music and I had to make it work, and I did. Everyone has self-doubt, but failing with Creation wasn’t an option.”

Primal Scream frontman Bobby Gillespie, who shared a teenage love of punk with McGee in the southside of Glasgow, describes him as “an instigator and motivator, a born upsetter”, while Oasis songwriter Noel Gallagher said McGee “gave me, and many people like me, a chance to change my life”.

But the hedonistic lifestyles of many of the label’s bands were notorious and the hard partying almost led to McGee’s demise, with a breakdown and spell in rehab finally forcing him to clean up his act.

McGee started the label in 1983, having moved south to London from his home city of Glasgow. He signed bands like The Jesus And Mary Chain and My Bloody Valentine, and became a master of promoting his bands to the music press. Most famously, he signed Oasis after hearing them playing at King Tut’s in Glasgow and led them to become the biggest band in Britain.

All that and more is portrayed in the film, and it’s with his typical matter-of-fact style that McGee, 60, reacts to seeing his life played out on the silver screen.

“The biggest compliment I can pay it is I don’t hate it – I can live with it. And when it’s a film about you, that’s quite a compliment,” he said. “Ewan McGregor was proposed to play me and I said I don’t look like that, so two days later they said what about Spud (Bremner’s character in Trainspotting) and I said, ‘100%. That will work’.

“For me, he’s the better actor, so it suited me, and I think he portrays me really well. He really got me. When I went on set the first time, he was in The Living Room, our old club, and he had the hair like me in 1988.

“I was there for about seven hours and it got really weird. I realised you don’t spend seven hours watching someone playing you – you go in and out in an hour and it’s fine.”

Last year, Bremner told The Sunday Post: “It’s a mad film and I really think it’s going to be something else. Fingers crossed they can keep the excess and passion of it, because there are some things in the film that may make the distributors nervous. I’m hoping they can maintain the integrity of it and not be forced to compromise too much.”

And McGee believes that has happened.

“I thought there would be certain parts cut out, like a scene with Jimmy Savile, but everyone got it, which is phenomenal, so respect to everyone involved.

“It’s real life but it’s Irvine Welsh as well. I had to give him and Nick Moran, the director, the artistic licence to do it the way they wanted to do it. It’s part reality, part fiction. There are things like me heading into the sunset with my dad, when the truth is I haven’t spoken to him for 20 years because we don’t get on.”

McGee wound up Creation Records in 1999 and started a new label, Poptones. Today, he remains a manager to several acts and also runs a new label, It’s Creation Baby, but no longer considers himself part of the music industry.

“I’m still putting out records and managing bands, but the industry is somewhere else – I don’t think they know who I am any more. I’m a little maverick indie manager and that’s what I do,” he said.

“I’m in the middle of putting out a solo album from Kyle Falconer, of The View, and if I get it on the radio I think it’ll be huge, as the record is full of hits. It’ll be interesting to see if I can break someone in a pandemic.

“I think there will be less places to play by the end of this. There will be lots of venues out of business and possibly a lot of people giving in. I think it’ll be 2022 before we can start playing shows again.”

With his destructive days long in the past, McGee used lockdown to get fit.

“I was fat for a long time, then I lost 36lbs,” he added. “So if I got anything out of lockdown, it was getting healthy.”

Creation Stories premieres at the Glasgow Film Festival, which runs from February 24 to March 7 and will be available on Sky Cinema from March 20.

If hip hop and acid house were Celtic, indie was Rangers… but Creation did both

Writer Paolo Hewitt says it was McGee’s passion for music that drove his success.

The former NME journalist, who wrote Alan McGee & The Story Of Creation Records, as well as two books on Oasis, said: “Alan’s always been about the music and he never became Johnny Big Shot like a lot do.

“Music was always the focus, the driving force, and it kept him grounded. He wasn’t on an ego trip.”

McGee partied as hard as he worked, and the lifestyle caught up with him a decade later when he suffered a breakdown.

“He took it to the extreme, and he said when they carried him out that he never ever wanted to feel like that again, and that’s what put him on the road to recovery,” said Paolo. “But he was also able to be self-deprecating about it, he saw the cliché in it and poked fun at himself for falling for it. He’d seen it happen to others and then it happened to him.”

Paolo spent time on the road with Oasis as they toured America in the mid-90s and he says it wasn’t as out of control as was so often portrayed.

“However much was going on, they were never too wasted to play the gig. Things are always overstated, it’s like Chinese whispers.

“It did go on, obviously, no one is denying it, and I think Oasis were clever that they fronted up about it straight away, so when the tabloids did stories about them taking drugs, the rest of the country said, we know, they’ve been telling us for the past two years.”

Paolo first came across Creation in the label’s early days while he was

at NME.

“It wasn’t for me at that point,” Paolo said. “It was very polarised and antagonistic, with everyone vying for the magazine covers. It was like football rivalries.

“If what I was into, hip hop and acid house, were Celtic, then indie music was Rangers. But Creation went on to engage with the acid house scene, which led them out of indie and into something like Oasis. They were much more interesting to me in the ‘90s rather than the ‘80s.”

Paolo believes McGee’s tense relationship with his father, played in the movie by Richard Jobson of The Skids, fed into his music obsession.

“If you’re listening to music then you’re not obsessing about whatever trauma you have. That’s why the arts become so important to so many people – they transport you out of the situation you’re in,” he added.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Francesco Guidicini/Shutterstock

© Francesco Guidicini/Shutterstock © David Wala/Shutterstock

© David Wala/Shutterstock