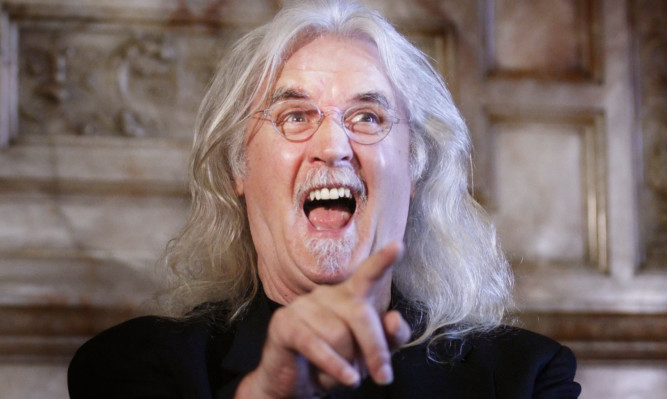

Big Yin still going strong despite Parkinson’s disease.

I can’t remember exactly the first time Billy Connolly made me laugh.

It was probably that iconic ITV special “An Audience With Billy Connolly” in 1985 funny walks and anecdotes about coats for duvets which I watched religiously every time it was repeated throughout my teens.

So it was nice for me to be able to get a laugh from Billy. Returning the favour, as it were.

I was reciting a story about a family boating holiday to mark my dad’s 75th birthday a similar set-up to his new film What We Did on Our Holiday.

In the words of Billy, it’s “a lovely wee thing” (I concur) in which he plays a grandfather whose family gather in the Highlands to celebrate his 75th birthday. David Tennant and Ben Miller play his warring sons.

“They’re difficult to manage, families,” says the Glaswegian funny man.

“People develop in different directions and it seldom meets up with the original plan. I remember being quite horrified in America hearing people talk about Thanksgiving and having to go to see their parents.

“I actually got my kids together after that and said, ‘Listen, if ever you feel like that, don’t come.’”

Getting the children together is increasingly difficult for the father of five these days.

Eldest son Jamie lives in Los Angeles, daughters Scarlett and Amy are in New York while Daisy and Cara, the mother of his two grandchildren, are in Scotland.

Billy and his second wife, the multi-talented Pamela Stephenson, are now based in New York having sold their palatial mansion in Aberdeenshire last year.

“When we get together it’s lovely,” says the 71-year-old, who beams with pride when talking about his family.

“We all get on like a house on fire, but arranging it is a nightmare. We are all trying to be in Australia (where Pamela is directing a show she’s written about a Brazilian dance called Brazouka) for Christmas this year but working it out is nigh on impossible.”

Billy and I meet in a suite at London’s Soho Hotel the night after the premiere of his new film. From here he’s heading north to embark on a month-long comedy tour of his native land.

The 22-date schedule may come as a surprise to those who read of his Parkinson’s disease and prostate cancer last year. He felt compelled to make an announcement about the Parkinson’s after it was incorrectly reported that he had dementia.

“I was quite offended and it wasn’t helpful at all so I felt I had to put the record straight,” he says.

Although he’s slightly slower in his delivery and may be working harder to pay attention to what you say (he has also had a hearing aid fitted) he is sharp and opinionated.

The prostate cancer, which he was suffering with but never mentioned to anyone on set while filming What We Did on Our Holiday, is happily under control while the Parkinson’s is a slowly degenerative condition he is learning to live with.

“It’s only going to get worse,” he tells me, striking a rare sombre note before an impish grin returns to his face.

“So that’s something to look forward to. It’s funny, when I look back at some earlier series of mine, like Route 66, I can see it in my movement. I couldn’t at the time, of course, but it’s probably something I’ve had for a while.

“It affects me very little. Sometimes I have a wee problem with stairs and I don’t play the banjo as well as I used to but I don’t think in terms of what I can’t do. I get on with my life in spite of it.

“The Chinese have a saying, ‘Death seeks hands with nothing to do’ and I think it’s very important to have a function.

“I used to see guys in the shipyards who retired, they’d worked there for 30 years and you’d see them off with a watch and a wallet with some money in it.

“They’d come in to the pub at lunchtime every day for a month after their retirement, then the second month they’d appear two or three times and after the third month you wouldn’t see him again and 18 months later the word would come in he was dead. And he was quite healthy at 65.

“But they lost their aim, their function, and suddenly they’re sitting at home staring at the wallpaper. It’s an absurdity.”

His time spent in Glasgow’s shipyards comes up frequently in conversation with Billy, a place where he began to realise there was another life away from the overbearing aunts who raised him after his mum walked out on him as a three-year-old. Or the father who abused him for four years from the age of 10, as revealed in Pamela’s biography of her husband.

“I was really happy when I was in the shipyards, all these new friends, it was lovely,” he accords. “I never wanted to be a foreman or anything.

“I’ve never been an ambitious guy, I’ve been managed by ambitious people. I was dragged screaming from the folk clubs and put into the concert halls by my manager Frank Lynch. It was hugely successful but it wasn’t my idea.

“And my move into comedy came about because Gerry Rafferty was better than me at songwriting (the pair performed together as folk band The Humblebums).

“I was doing these comic monologues between the songs and they were getting longer and longer.

“I remember we were sat down in Queen Street station, on our way to the east coast to play a show in Arbroath or Dundee, I can’t quite remember, and I said, ‘Look, I think we’ve got to stop this,’ because I think I was beginning to irritate him.

“And then he’d perform a lovely song and I’d walk off. ‘Summertime’ accompanied to the sound of my feet walking across the stage towards the exit!”

We both laugh at the image. When you’re in the company of Billy Connolly, laughter is a shared experience.

Our Verdict – 5/5

A joyous film that manages to make you leave the cinema feeling good despite tackling the subjects of divorce, mental breakdown and terminal cancer.

This is in large part down to the performances of the three young children involved, five-year-old Harriet Turnbull, Bobby Smalldridge, aged six, and Emilia Jones (11), whose lovability shines through in the improvised style that the film’s directors, Guy Jenkin and Andy Hamilton, have used previously on the BBC sitcom Outnumbered by its creators.

The summer season may be over, but this a Holiday I’d happily revisit time and time again.

What We Did on Our Holiday is at cinemas now. Billy’s High Horse tour begins on Monday, September 29, in Aberdeen. For further dates, see www.billyconnolly.com.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe