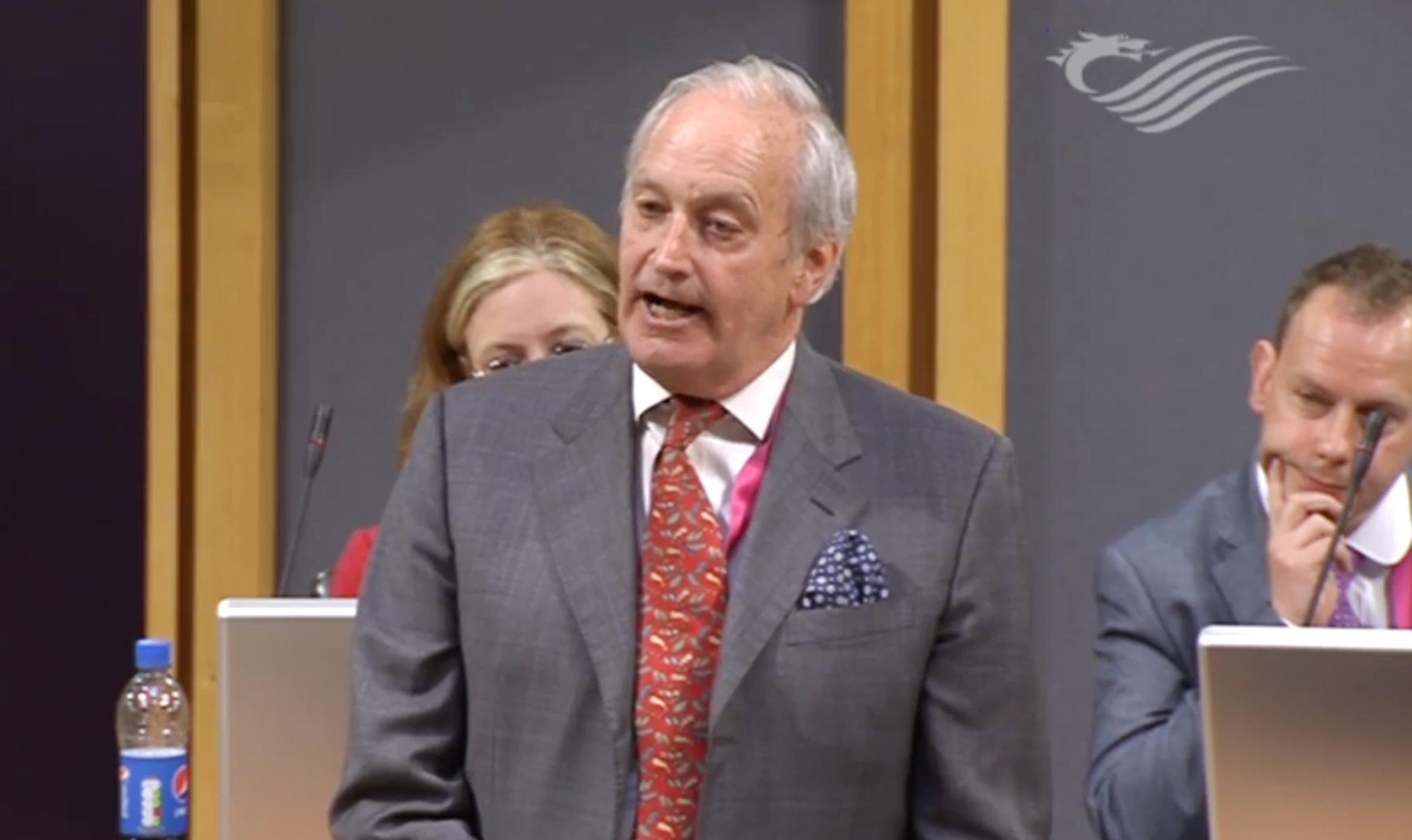

He’s a “big boy”. That was the response of Ukip’s Neil Hamilton when accused of bullying his Welsh Assembly colleague Nathan Gill.

The former Tory dismissed the allegations, asking how he could possibly bully a man of 6ft 6in – as if size were somehow relevant.

It’s a telling episode.

He’s a “big boy”. The implication: he should be able to handle it.

And – as the Conservative bullying scandal has so disturbingly exposed – it’s clearly not a minority attitude either.

The findings of law firm Clifford Chance, brought in to investigate bullying allegations following the suicide of Tory activist Elliott Johnson, were branded a whitewash by his family.

But the report did shed some light on the kind of behaviour deemed acceptable within political parties.

If there had been warnings about Mark Clarke’s “aggressive” past conduct, why did former Tory co-chairman Grant Shapps appoint him to a key campaigning role during the general election?

If there had been seven complaints against the so-called Tatler Tory, who denied the bullying allegations, what took the party so long? Had earlier action been taken, then Mr Johnson – whose complaint against Mr Clarke finally triggered the internal investigation – might still be with us.

The party responded to the report by setting up new procedures to handle complaints by volunteers, including a dedicated hotline and training for employees.

It was a start, but at the very least there should now be a fully independent and transparent inquiry.

There must also be a comprehensive attempt to tackle the ‘if you don’t like it, there are plenty of others who will’ mentality.

In any competitive field – journalism and law are good examples, too – this approach seems deep-seated. There’s a sense that newcomers should be so grateful for being handed an opportunity that they should be prepared to put up with anything.

This is fundamentally wrong. What about a duty of care, especially in relation to volunteers?

In a political context – with, say, the prospect of a parliamentary seat further down the line – it becomes even more toxic.

I suspect and worry there are other Mr Johnsons who are keeping their heads down, taking it on the chin, until the day they crack.

Complaints of bullying in the Labour Party provide evidence that this entrenched issue crosses the political divide.

In July, former shadow Cabinet minister Seema Malhotra spoke of a “culture of bullying” which needed to be stamped out.

The same month, Wallasey Constituency Labour Party group was suspended following accusations of intimidation.

There have even been allegations – again rejected – directed against Jeremy Corbyn. The party leader was forced to deny he was a bully after senior Labour critic Conor McGinn claimed he had threatened to call his father, a Sinn Fein councillor, to apply pressure on him to stop speaking out.

The St Helens North MP called Mr Corbyn a hypocrite for talking about a “kinder, gentler politics” while purportedly proposing to use his family against him.

Let’s also not forget the suspensions of Naz Shah and former London mayor Ken Livingstone amid anti-Semitism claims.

In an article published earlier this month, Ann Carlton, a former Government special adviser, drew comparisons between the 1981 deputy leadership election and the current tussle between Mr Corbyn and Owen Smith.

She described “personal nastiness against people who had served the party loyally for decades” as the “hallmark of many political meetings”.

Whatever her motivations in writing, it seems this ugly and harmful culture is far from a new phenomenon.

Surely it is finally time for political parties to professionalise and tackle the issue head-on?

READ MORE

Lindsay Razaq: Labour movie would have a great plot, but no box office clout

Lindsay Razaq: Dishing out honours to cronies exposes David Cameron’s true colours

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe