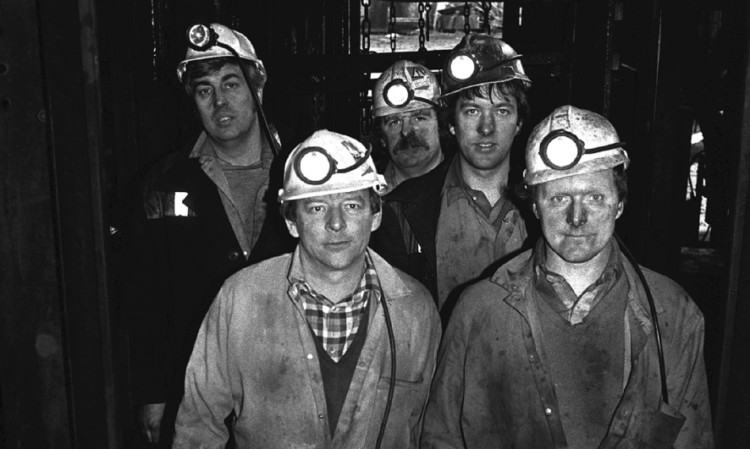

Communities and families suffered terribly during bitter battle.

It’s a gloomy Wednesday afternoon in east Ayrshire the rain is coming down thick, the streets are empty and there is little sign of life.

It’s a bleak scene reminiscent of many communities in recession-hit Britain, except this has been the way of things in these parts for more than the past few years.

It was on March 6 1984, that the National Coal Board announced plans to shut 20 pits across the UK.

Just six days later, National Union of Mineworkers president Arthur Scargill called on all NUM members to down tools.

The strike lasted a few days short of a full year, finally finishing on March 3 1985.

Many of the jobs to go were in Scotland and the north-east of England.

At the time there were 250,000 mining jobs in the UK around 15,000 of those were in Scotland.

Now, there are just 5,000 British posts with only a few hundred surface mining jobs north of the border.

Just like the coal that is the foundation of the Ayrshire countryside, it doesn’t require much digging to unearth the communities’ feelings on the strike and its disastrous impact.

The landlady behind the bar in a New Cumnock pub says the place is different quieter from the town she was brought up in. She points towards a grassy hill overlooking the town.

There’s a road, street lights and broken steps leading nowhere, a sad reminder of the houses that were flattened when the population dwindled.

“Most folk have to go elsewhere for a job these days because there’s nothing around,” says Jim Whiteford, as he sits in a pub in nearby Dalmellington.

“You just have to look around to see how badly the places struggle.”

Jim is 75 now but his handshake’s grip remains strong, fostered by 32 years down the mines.

He knew from the first day that the men wouldn’t win, but it was in his nature to take part.

“We had no money, so it was tough. My sister in Stewarton would bring a supply of food and tins. Some of the drivers would give us coal, others would hand money down and tell us to enjoy a pint.”

Further up the road in Logan, Jim McMahon leans against his bar in the Glenmuir Arms. He worked in the pits from 1979 until 1994.

The strike became key part of Margaret Thatcher’s legacy as prime minister and it’s telling that Jim held a celebration in his pub when she died.

“The strike shaped my whole life my morals, my scruples,” the 53-year-old said.

“I was there from the first day to the last. It was a long, hard year but I would do it again.”

He pauses, rubs his face and then shakes his head.

“I clearly remember the day we went back to work, knowing we were beat, and the massive consequences it would have on the area.

“We recently counted 6,000 jobs lost to the area through the pits, the workshops and so on.

“There’s been no reinvestment or anything else since.”

There was a lot of tension among families as the strike wore on.

Helen Gray, from Netherthird, was a mum-of-three in her early 30s at the time.

Her husband Robert’s £70-a-week wage became less than £15 and hefty cuts had to be made.

“Our kids were just seven, 11 and 15 and it was very difficult,” said Helen.

“I made a lot of soups and stews that would last three days good wholesome food that didn’t cost much.

“I saw my dad coming down the street with a suitcase one day and worried that he was coming to stay.

“But it was actually full of food.”

With three killed, 200 imprisoned, and 20,000 injured during the year-long demonstrations, it was a dark time for the country and its people.

Bert Smith, 73, from Cumnock, was a miner for almost 30 years before being sacked during the strike.

“My two girls had just left school and my son was unemployed at the time, so it was really tough,” said dad-of-five Bert (pictured below).

“If you’re used to living hand-to-mouth most of your days, you get by but it was certainly no picnic.

“An amazing community spirit built up though and women were right at the heart of it.

“The strike committees became the centre of villages.

“Even if they weren’t political, a lot of women got comfort from meeting up and sharing their problems.”

Bert added: “We could see the whole thing coming, but didn’t think it would be as savage as how it turned out.”

The strike was a defining moment in British industrial relations and, as a result, the political power of the NUM and of other trade unions was severely reduced.

Current president of the Scottish NUM Nicky Wilson was a young miner at

Cardowan Colliery in Stepps.

“I was married with two kids and luckily my wife had a couple of part-time jobs to help see us through,” said Nicky, 63.

“Many would never have got through if it hadn’t have been for the people who gave to the collections and help from elsewhere.

“I remember people donating gifts for miners’ families that Christmas and the generosity was amazing.

“My wife stood by us, but sadly that wasn’t the case with every family and some marriages just went under.”

Nicky has been a vice chair of the Coalfields Regeneration Trust since it was set up in 1999.

It aims to improve the quality of life among struggling former mining communities.

He adds:“I’ve seen first-hand the devastating impact the pit closures has continued to have.”

In a cruel echo of the past, communities in east Ayrshire suffered a fresh mining blow last year when open cast mines shut with the loss of over 300 jobs.

“That would have been the size of a small colliery at one time,” said local councillor and former miner Barney Menzies.

“We’ll never get back to where we were.

“People didn’t sit on their hands and went elsewhere, even abroad, to find work.

“That hits the local economy, shops and the like.”

Barney was one of those made redundant last year after almost 40 years in the mining industry. He was working at the Barony pit in 1984.

“I saw families split and

friends part ways because of the strike.

“But it showed the good side too.

“There were 26 strike centres in Ayrshire at the time and I remember every one getting a 25lb turkey sent from well-wishers for families at Christmas.”

Albert Wheeler became director of the Scottish division of the National Coal Board in 1980.

His abrasive management style and hardline attitude towards the workers were infamous and made him a hated figure.

Dr Andrew Perchard, of the University of Strathclyde, is the co-author of a paper about Wheeler.

Dr Perchard said: “Wheeler had a different vision from a lot of the managers.

“He had a market-orientated vision, whereas some of the older managers viewed it as a social enterprise.

“People were outspoken because they felt he purposefully tried to kill the industry, but I think he believed he was helping the business.

“His personality had a lot to do with how the strike went.

“He was confrontational and purposefully so, as a way to prompt action and create flash points.

“He was absolutely critical of the strike and afterwards he ensured that anyone who had been arrested on the picket lines, even if they weren’t convicted, weren’t allowed to go back to work down the pits.”

Just like the coal that is the foundation of the Ayrshire countryside, it doesn’t require much digging to unearth the communities’ feelings on the strike 30 years on.

Three decades may have passed, but these villages and towns are still dealing with the consequences.

As such the memories remain vivid too vivid still for many to openly talk about and as dark as the pit face that generations of men worked at.

The Sunday Post’s Murray Scougall visited the area to speak with some of those still feeling the effects of the strike.

It’s a bleak Wednesday afternoon when I arrive in east Ayrshire.

The rain is coming down thick, the streets are empty and there is little sign of life.

It’s a scene reminiscent of many communities in recession-hit Britain, except this has been the way of things in these parts for more than the past few years.

The landlady behind the bar in a New Cumnock pub says the place is different quieter from the town she was brought up in.

She directs us towards a grassy hill overlooking the town.

There’s a road, street lights and broken steps leading nowhere, a sad reminder of the houses that were flattened when the population dwindled.

“Most folk have to go elsewhere for a job these days because there’s nothing around,” says Jim Whiteford as he sits in a pub in nearby Dalmellington.

“You just have to look around to see how badly the places struggle.”

Jim is 75 now but his handshake’s grip remains strong, fostered by 32 years down the mines.

He knew from the first day that the men wouldn’t win, but it was in his nature to take part.

He only returned to work three weeks before the strike ended.

“We had no money, so it was tough. My sister in Stewarton would bring a supply of food and tins.

“Some of the drivers would give us coal, others would hand money down and tell us to enjoy a pint.”

Further up the road in Logan, Jim McMahon leans against his bar in the Glenmuir Arms.

He held a celebration there when Thatcher died.

Jim worked in the pits from 1979 until 1994.

“The strike shaped my whole life my morals, my scruples,” the 53-year-old said.

“I was there from the first day to the last. It was a long, hard year but I would do it again.

“My wife had a job, so we weren’t quite as bad off as others, but I had to get rid of my telly because I couldn’t pay the licence.”

He pauses, rubs his face and then shakes his head.

“I clearly remember the day we went back to work, knowing we were beat, and the massive consequences it would have on the area.

“We recently counted 6,000 jobs lost to the area through the pits, the workshops and so on.

“There’s been no reinvestment or anything else since.”

By Bill Gibb and Murray Scougall

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe