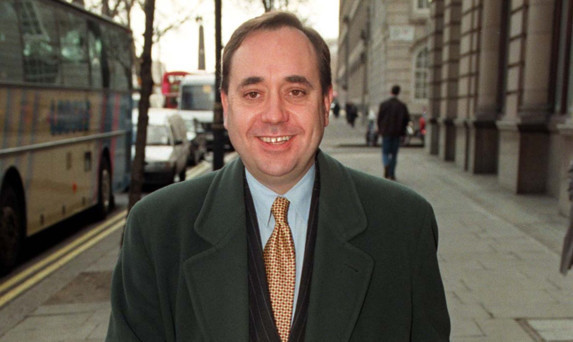

SNP leader has embraced more currency policies than most in the years leading to the independence referendum.

There’s a video on YouTube of “The Great Debate”, a 1995 showdown between Alex Salmond and George Robertson, then Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland.

Under cross-examination from journalists like Andrew Marr and Jim Naughtie, and under often incisive questioning from members of the audience, the SNP leader and his Labour nemesis jousted over familiar territory whether Scotland could afford to go it alone, membership of the European Union, and so on.

They also discussed monetary policy. On this, Salmond cited the difficulty of using Scottish banknotes in London and abroad.

“If Scotland has an independent currency,” he said, “at least we’ll have a first-class currency like everyone else and not a second-class sterling as we have now.”

Assured and polished, on this and many other areas, Salmond was seen to have got the better of Robertson.

But two-and-a-half years later, speaking at a dinner hosted by the European Movement, the SNP leader announced his party would back Scottish membership of the European single currency, as yet unlaunched, and thus far from being unloved.

“It is time those in favour of progress upped the ante and confronted not just the jingoistic Euro-scepticism of the Tory rump in Parliament,” he subsequently wrote in a newspaper article, “but also the incompetence of new Labour in government.”

At the time, this currency shift attracted little comment, for in the wake of Labour’s 1997 landslide, the SNP was far from being a credible party of government, let alone in a position to implement policy.

There was, however, internal dissent, certain Nationalists having always regarded Brussels rule as just as bad as that from London.

A year later, Salmond was brushing aside criticisms of his enthusiasm for Euro membership, the details of which he regarded as “trivial” or issues of mere “management”.

“It’s our policy to seek entry”, he stated simply, “because we think it’s in Scotland’s economic interest to do so.”

But even back then, the future First Minister was cautiously trying to square circles. Monetary control via the European Central Bank was considered a step too far.

“We’re very pro-EMU, and we’d probably make do with the European Monetary Institute in Frankfurt,” he said on the eve of the 1998 SNP conference. “It would be to everybody’s convenience to maintain parity with sterling until entry.”

As with many statements of party policy particularly in opposition the SNP’s commitment to joining the Euro quietly slipped away rather than being explicitly dumped.

In another little-noticed policy paper published in 2005, “Raising the Standard”, the SNP matter-of-factly stated that in an independent Scotland the “currency shall continue to be sterling until such time as Parliament decides to change that position”. This was deliberately open-ended, giving the party the option of pursuing what would now be called Plan B (a separate Scottish currency) or even Plan C (joining the Euro) at some point in the future.

But it was only under the cold light of the referendum microscope that opponents and financial experts noticed the SNP’s paradoxical commitment to a currency union and started picking it apart, often with brutal force.

Of course, and as the First Minister pointed out under fire last week, his is not the only party to have chopped and changed on currency. Labour, too, was once rather keen on membership of the Euro, although it ditched that plan long before the SNP.

But it remains the case that Alex Salmond had three different currency policies between 1997 and 2005 more than most.

Furthermore, this political sleight of hand became the central plank of the SNP’s de-risking strategy in the run up to the independence referendum, demonstrating to voters fearful of change that while a “yes” vote would benefit Scotland, it would do so using the trusty old British pound.

This tactic was borrowed from overseas in the run up to a 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty in Canada, the Parti Quebecois pledged to retain the Canadian dollar.

But that ended up being unsustainable. Even many of those supportive of Quebec independence considered a Canadian currency union incompatible with full sovereignty.

The SNP has found itself in a similar position while now, just months from the referendum, Nats find themselves in the curious position of unwittingly echoing William Hague’s 2001 battle cry: “Keep the Pound!”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe