Muhammad Ali’s daughters reveal the soft side behind his punch power and his battle with Parkinson’s 40 years on from the Rumble in the Jungle.

Forty years ago this week six-year-old Maryum Ali was sitting in front of a television set at her home in Chicago.

Her arm was aching and she was disappointed that her pain had been pointless.

On the grainy screen, she was watching her “daddy”, better known to the rest of the world as Muhammad Ali, pull off one of the greatest comebacks since Lazarus using the punishing tactics of “rope-a-dope” to allow George Foreman, the heavyweight champion of the world and one of the fiercest punchers the division had ever seen, to exhaust himself in the stifling heat of Zaire.

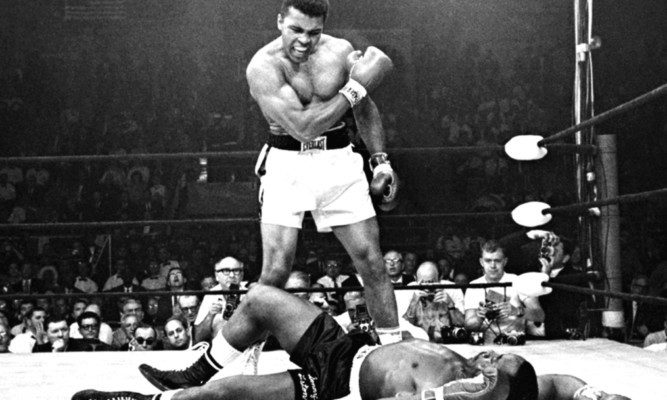

“Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see,” the 32-year-old former champ had goaded his rival in the build-up to the Rumble in the Jungle. But from an early stage in the fight he hardly moved off the ropes until satisfied Foreman had punched himself out. In the eighth round he delivered the coup de grace to regain his title.

“I was supposed to go to that fight,” Maryum, affectionately known as May May by everyone that knows her, tells me. “I got my booster shots for Africa, they left a mark on my arm, but at the last minute I was told I couldn’t go.”

Despite being one of her father’s greatest achievements in a career full of them Kinshasa was not Ali’s finest moment on a personal level. For it was in the central African country that he met and fell in love with Veronica Porche, an 18-year-old model employed by promoter Don King to add glamour to the occasion.

Fearing something was going on, Maryum’s mum, Belinda, caught the pair of them together on a surprise visit to the Intercontinental Hotel.

“My father was a good man but he wasn’t a faithful one,” says Hana Ali, eldest daughter from his eventual marriage to Veronica and now sitting alongside her half-sister Maryum.

Just how good is explored in a new documentary, I Am Ali, which opens at cinemas later this month. It’s a rare insight into Ali away from the bragging of the boxing ring.

READ MORE

Muhammad Ali: A life in pictures

5 of Muhammad Ali’s greatest fights

Boxing legend Muhammad Ali dies aged 74

Directed by a woman, British filmmaker Clare Lewins, and featuring testimony from many of the women in his life, including May May, Hana and Veronica (he has six daughters and a son from his four marriages and two other children from extra-marital affairs in all), it shows a gentler side to the man voted BBC Sports Personality of the Century in 1999 (he polled more votes than all the other candidates added together).

“I have seen him buy houses for his sparring partners, pay for people’s education, try to find people jobs,” recalls May May.

“I remember once when we were living in California he was in his Rolls Royce when he passed a family of four waiting at a bus stop. They were homeless and trying to get back to Florida and he brought them to the house, fixed them up with a meal and then put them all on a train back to Florida.”

“I remember him leaving the house once to talk down a young man he’d seen on the news who was threatening to throw himself off the side of a building,” adds Hana.

His role as May May’s father was mostly an absent one. She was raised by her grandparents but spoke to him regularly on the phone. Ali recorded all his phone calls and the tapes of his talks to his young daughters make up an important part of the documentary. There’s a very touching moment where an 11-year-old May May tries to talk a slurring Ali out of making a comeback in the late ‘70s.

“I was still a child but every time I saw him he was a little slower and speaking a little softer and even then I felt that was from boxing.”

Hana’s upbringing was a lot different to May May’s. She was five when Ali fought his last professional bout, a points defeat to Trevor Berbick in December 1981, and remembers him being there most mornings to wake up her and sister Laila with kisses.

By that time the love he had for other people was being reciprocated everywhere.

To the affection was added pity in 1984 when Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. For the next decade he scaled down his public appearances and those he did make usually entailed a wave and a smile, leading people to believe his condition was worse than it was.

“It took a while for him to face up to his Parkinson’s,” says Hana. “His mind was still sharp but he was conscious that his voice was slurred so people would ask him questions and he would just smile and nod. I used to say to him afterwards, ‘Why didn’t you say something? We know you can talk’.

“He came to terms with it eventually but it was very hard because he was so articulate and now it was taking him so long to say what he wanted to say.”

A change in outlook came after the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta when a trembling Ali lit the Olympic flame.

“My step-mum (Ali’s fourth wife, Yolanda) told me that after my father lit the torch he stayed up all night, sat in the chair with the torch in his hand just looking at it.

“He was so humbled by the experience and the crowd’s reaction to him and I think he was more comfortable living with his Parkinson’s after that.”

Both daughters put a positive spin on his current condition, despite reports he is no longer able to communicate Hana says she speaks to him “when he can” on the phone.

“He’s not in any pain physically, he never questions, ‘why him?’ He believes everything has a purpose and he’s happy being Muhammad Ali.”

When you’re still known simply as “The Greatest” four decades on from proving it wasn’t just talk, why wouldn’t you be?

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe