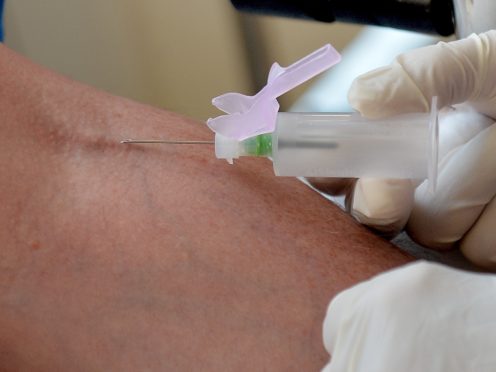

Detecting Alzheimer’s disease through a blood test has moved a step closer to clinical use.

A new blood test is 94% accurate at identifying Alzheimer’s before symptoms arise when age and genetic risk factors are taken into account, experts have said.

Researchers from Washington University in St Louis report they can measure levels of the Alzheimer’s protein amyloid beta in blood and use these levels to predict whether it has accumulated in the brain.

The report said that up to 20 years before people develop the memory loss and confusion of Alzheimer’s disease, damaging clumps of protein start to build up in their brains.

The findings, published in the medical journal Neurology, are a major step towards a blood test to diagnose people on track to develop the disease, before symptoms arise.

“Right now we screen people for clinical trials with brain scans, which is time-consuming and expensive, and enrolling participants takes years,” said senior author Randall J Bateman, professor of neurology in Washington University’s medical school.

“But with a blood test, we could potentially screen thousands of people a month.

“That means we can more efficiently enrol participants in clinical trials, which will help us find treatments faster, and could have an enormous impact on the cost of the disease as well as the human suffering that goes with it.”

The study involved 158 adults aged over 50.

All but 10 of the participants in the study were cognitively normal, and each provided at least one blood sample and underwent one positron emission tomography (PET) brain scan.

The researchers classified each blood sample and PET scan as amyloid positive or negative, and found the blood test from each participant agreed with his or her PET scan 88% of the time.

In an effort to improve the test’s accuracy, the researchers incorporated several major risk factors for Alzheimer’s.

Age is the largest known risk factor; after 65, the chance of developing the disease doubles every five years.

A genetic variant called APOE4 raises the risk of developing Alzheimer’s three to five-fold, and gender also plays a role as two out of three Alzheimer’s patients are women.

When the researchers included these risk factors in the analysis, the accuracy of the blood test rose to 94%.

The research found that sex did not significantly affect the analysis.

“Sex did affect the amyloid beta ratio, but not enough to change whether people were classified as amyloid positive or amyloid negative, so including it didn’t improve the accuracy of the analysis,” said Suzanne Schindler, an assistant professor of neurology.

The results of some people’s blood tests were initially considered false positives because the blood test was positive for amyloid beta but the brain scan came back negative.

But some people with mismatched results tested positive on subsequent brain scans taken an average of four years later.

The finding suggests that, far from being wrong, the initial blood tests had flagged early signs of disease missed by the brain scan.

The researchers hope a test will become available at doctors’ offices within a few years.

They say its benefits will be much greater once there are treatments to halt the disease process and forestall dementia.

Clinical trials of preventive drug candidates have been hampered by the difficulty of identifying participants who have Alzheimer’s brain changes but no cognitive problems.

The blood test could provide a way to efficiently screen for people with early signs of disease so they can participate in clinical trials evaluating whether drugs can prevent Alzheimer’s dementia.

There is growing consensus among neurologists that Alzheimer’s treatment needs to begin as early as possible, ideally before any cognitive symptoms arise.

By the time people become forgetful, their brains are so severely damaged no therapy is likely to fully heal them.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe