THEY used to be thought of as just country dwellers – and the subject of controversial hunts.

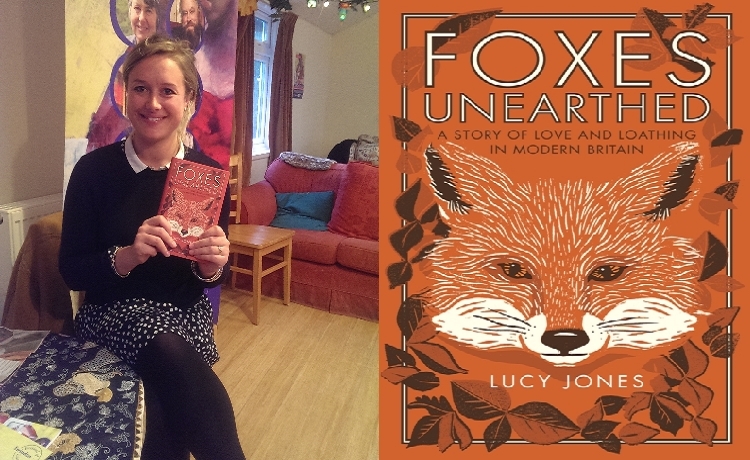

But now foxes are seen around our towns and cities. Lucy Jones, author of Foxes Unearthed (Elliott and Thompson), tells Bill Gibb The Honest Truth about the creatures.

Why did you want to write a book about foxes?

I was fascinated by how divisive the red fox is in this country, more so than any other species.

People either love or loathe the fox and I wanted to find out what was behind that.

And, traditionally, there was hunting and farming in the Scottish side of my family so I was aware that the fox could be a flint for emotions and ethical questions.

How many different species are there?

There are 12 species, each adapted to its environment, from the tiny, big-eared fennec of the Sahara to the snow-white Arctic fox in Iceland.

What type do we have here?

The red fox is indigenous to Britain and the oldest remains date back to the Wolstonian period (between 130,000 and 352,000 years ago).

They are, of course, red, which is one of their defining features.

They are thin and on average only between 46 and 86 centimetres long, excluding the tail which can be another 30 to 55 centimetres. So, they’re smaller than you might think.

Why do we see so many foxes in our towns and cities now?

Foxes started colonising our towns and cities gradually in the 1950s.

Partly, that was because of their relatively small and unobtrusive size – they can move around quite easily.

Another theory is that foxes made the jump to urban living because of the way the post-war suburbs trailed out into the countryside with typical

new-build houses having enough space – and often sheds – to provide the perfect home for fox families.

Foxes are now common in cities like Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh.

What about Tony Blair’s troubles over the hunting ban?

Blair described the passions aroused by fox hunting as “primeval”.

Writing in his autobiography after Labour brought in the Hunting Act – which banned hunting wild mammals with dogs – he said: “If I’d proposed solving the pension problem by compulsory euthanasia for every fifth pensioner I’d have got less trouble.”

Did Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox change people’s perceptions?

Before that, the fox was traditionally characterised as a plain villain, a chicken-pincher, a trickster and a dangerous thief.

Dahl retained the fox’s natural wild predatory impulses but he is a hero.

I delved into Dahl’s archives to see how he was keen for the fox to be a realistic hunter but also for the reader to delight and cheer in its success.

How did they get their reputation for being cunning?

Quite simply, the fox was perceived very early on as having an appetite – and being prepared to step into other animals’ (including human) spaces to

satisfy it.

The fox is a highly evolved hunter and successful at finding the food it wants to eat.

In real life the fox isn’t really all that cunning. In essence it is just doing what it is naturally wired to do.

What about human attack tales?

There have been a few, very rare incidents of foxes in homes which are labelled as “attacking” babies.

According to carnivore exports, a direct attack on a child would look different from the cases that have been reported.

Foxes will investigate an unknown object by using their mouths to explore it, which can lead to bites if the fox isn’t stopped, but these occasions have been very rare.

Foxes don’t see doors and windows as boundaries like we do.

READ MORE

How animals use tricks to get ahead in the natural world

Pets at Home name list of the most influential animals over the past 25 years

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe