IT was the biggest battle of the Great War on the Western Front, with more than a million men killed or wounded.

Exactly a century on, the world will remember the Battle of the Somme, and be reminded just how horrific those dark days were.

It was a battle that directly affected countless Britons as well as people as far afield as Australia, Bermuda, Canada, India and elsewhere.

So a newly-published book about it is most unusual, in that so many died during the first day of this horrific battle, there were precious few lads alive long enough to tell the tale of it.

One, however, was Edward Liveing, who wrote a vivid and detailed account of the dreadful first day of the Battle of the Somme, which was really a series of offensives fought over several months.

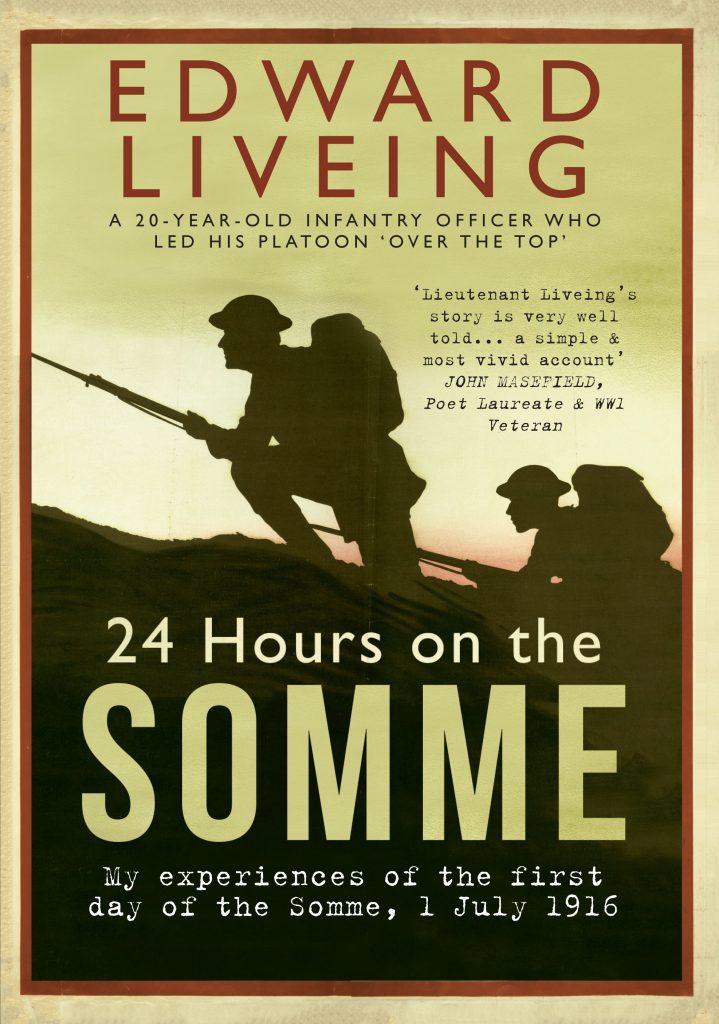

First published under a different title in 1918, 24 Hours On The Somme: My Experiences Of The First Day Of The Somme, 1 July, 1916, is an incredible true story.

A young junior officer in the London Regiment on the battlefield that infamous day, Edward was in command of a platoon of about 50 men when he scaled his trench into No Man’s Land.

Although his account is known, this is the first time since its publication in the USA in 1918 that it has been republished in its full, horrific, unexpunged glory.

“It was about three o’clock in the morning,” wrote Liveing. “I did not look at my watch, as its luminous facings had faded away months before and I did not wish to disturb my companions by lighting a match.

“I plunged farther down into the recesses of my fleabag, though its linings had broken down and my feet stuck out at the bottom.

“Then I pulled my British Warm over me and muffled my head and ears in it to escape the regularly-repeated roar of the 9.2.”

When he woke again at the back of seven, it was to the sound of enemy shells coming in and within minutes, several of his colleagues around him were dead or severely wounded.

In what would become one of the bloodiest battles of all time, the Allies had agreed on a strategy to take on the so-called Central Powers, essentially Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.

Britain alone would lose almost half a million men, France half that, Germany slightly less than half that.

The battle would also be notable for the importance of air power and the first use of the new-fangled tank. Despite all these weapons — some that soldiers had never faced before — Liveing couldn’t wait to go over the top into the unknown.

“I have often tried to call to memory the intellectual, mental and nervous activity through which I passed during that hour of hellish bombardment and counter-bombardment, that last hour before we leapt out of our trenches into No Man’s Land,” he wrote.

“I had an excessive desire for the time to come when I could go ‘over the top’, when I should be free at last from the noise of the bombardment, free from the prison of my trench, free to walk across that patch of No Man’s Land and opposing trenches until I got to my objective, or, if I did not go that far, to have my fate decided for better or for worse.

“I experienced, too, moments of intense fear during close bombardment. I felt that if I was blown up it would be the end of all things so far as I was concerned.

“The idea of afterlife seemed ridiculous in the presence of such frightful destructive force.”

German machine-gunners would pick off many of our young heroes.

“A continuous hissing noise all around one,” Liveing described it, “like a railway engine letting off steam, signified that the German machine-gunners had become aware of our advance.

“I nearly trod on a motionless form. It lay in a natural position, but the ashen face and fixed, fearful eyes told me that the man had just fallen. I did not recognise him then. I remember him now. He was one of my own platoon.”

To his own surprise, there was no fear once he was in the thick of it, and each second passed in a haze.

“If I had felt nervous before, I did not feel so now,” he described. “I felt as if I was in a dream, but had my wits about me.

“We had been told to walk. Our boys, however, rushed forward with splendid impetuosity to help their comrades and smash the German resistance in the front line.

“I kept up a fast walking pace and tried to keep the line together. This was impossible.

“When we had jumped clear of the remains of our front-line trench, my platoon slowly disappeared through the line stretching out.

“Eventually, Lance-Corporal M was the only one of my platoon left near me, and I shouted out to him: ‘Let’s try and keep together!’ It was not long, however, before we also parted company.

“One thing I remember very well was that a hare jumped up and rushed towards and past me through the dry, yellowish grass, its eyes bulging with fear.”

A 20-year-old junior infantry officer when he led his platoon of the County of London Regiment from the trenches on the Somme in the third wave at Gommecourt, Liveing later worked for the BBC, and died in 1963.

That made him one of the very, very lucky ones. British losses on that first day alone were the worst in British military history, with almost 58,000 casualties, nearly 20,000 of them killed.

It is only right that we remember what they endured so we could live freely today.

24 Hours On The Somme, by Edward Liveing, is published by Amberley, priced £9.99, ISBN No. 978-1-4456-5545-1

READ MORE

Love letters from First World War to go on display

First World War Tommies spent just half their time at the front

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe