But they were – one pink, one blue. She knew she hadn’t put them there, so who had?

There was a pen scrawl on the flap of the uppermost folder. Maggie slowly reached in and picked it up. Her breath caught as she saw the handwriting – she knew it only too well.

“Who the hell is Bill Anderson?” read the scribble.

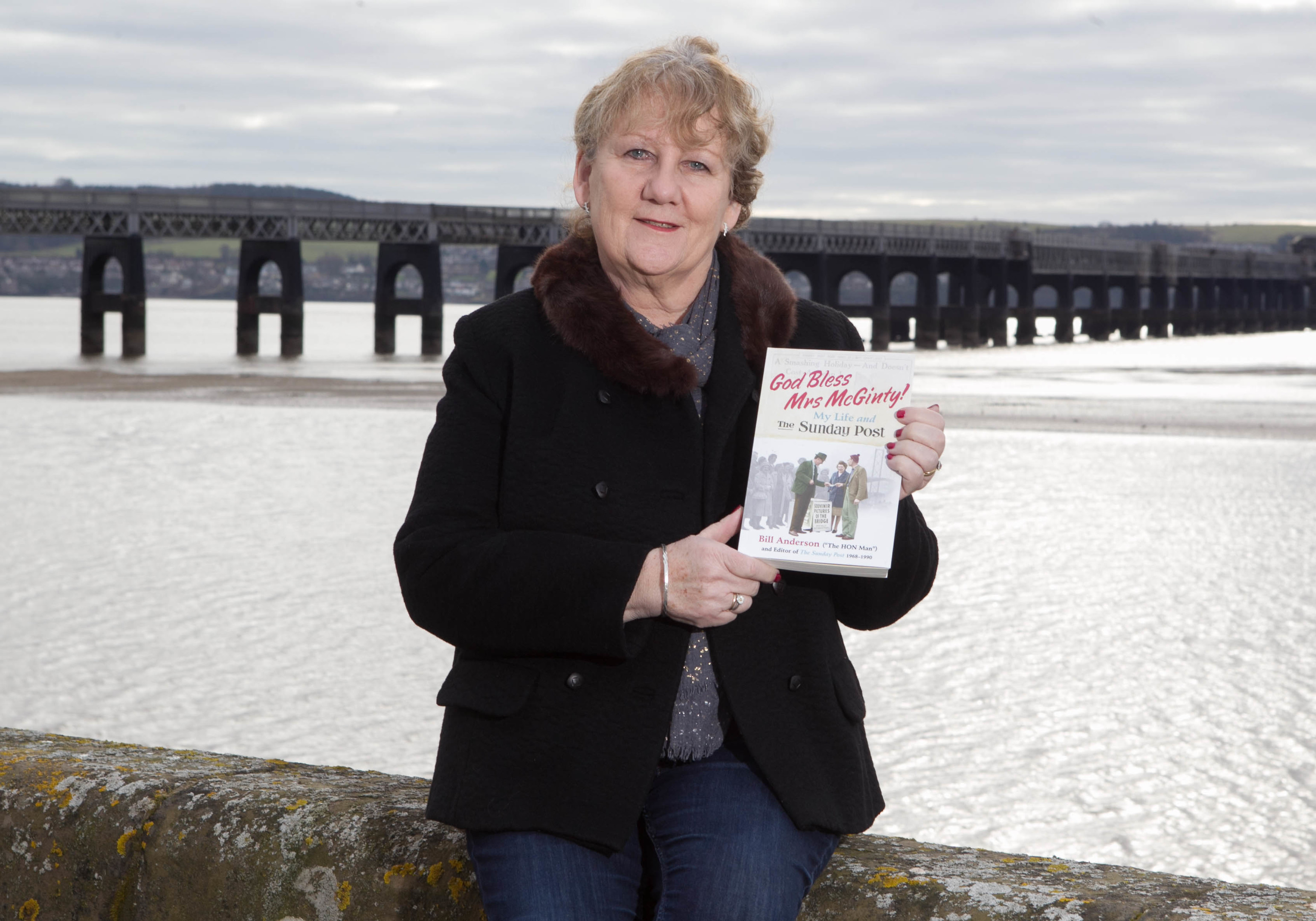

The answer, to Maggie, was her late husband, the legendary former editor of The Sunday Post.

She was confused. She was reading a story that, as far as she was aware, had never been written.

“After he stopped work in 2003 lots of people said to him, ‘when are you going to write a book’,” says Maggie in her stylish front room overlooking the River Tay. “He always said he had no intention of writing one, that nobody would be interested.

“Then in 2014 I was doing a clear-out. My desk was up the top of the house. Bill never went up there because he was quite bad on the stairs by that point. I opened the desk drawer and there were the two folders.

“I started reading and I thought, ‘Gosh! This is amazing’. I had a wee tear or two reading it.

“To this day I cannot understand how the folders got there. He’d never mentioned it. How had they got in my desk?”

The story contained in the mysterious folders now forms the basis of a new book, God Bless Mrs McGinty! (Mrs McGinty is the mythical ‘ideal Sunday Post reader’).

Published this coming Tuesday it opens in 1981 with Bill at the height of his powers as the most successful and formidable editor The Sunday Post has ever seen, before looking back over his life from growing up in a working-class household in 1930s and ’40s Motherwell, to joining the army and then becoming a roving reporter and editor with the Post.

Bill was born in 1934 to a steelworker father, John, who had lost a leg in a terrible workplace accident, and a mother, Bessie, an illegitimate child.

Perhaps because of her own background Bessie wasn’t a warm woman – cuddles never featured prominently in the Anderson household – but she was determined young Bill would make something of himself. He was a bright lad, Dux of his school, and Bessie reckoned it would add a certain shine to the family name if he became a doctor.

Just imagine! Doctor Anderson. She’d be the envy of her friends.

So Bill was pushed towards studying medicine at Glasgow University.

It didn’t quite work out, as Maggie explains.

“Bessie desperately wanted him to be a doctor and made him go to Glasgow University. But Bill spent all year playing bridge, so he failed first year.”

He gave it another go, but it clearly wasn’t for him, so he left uni, much to his mother’s disappointment.

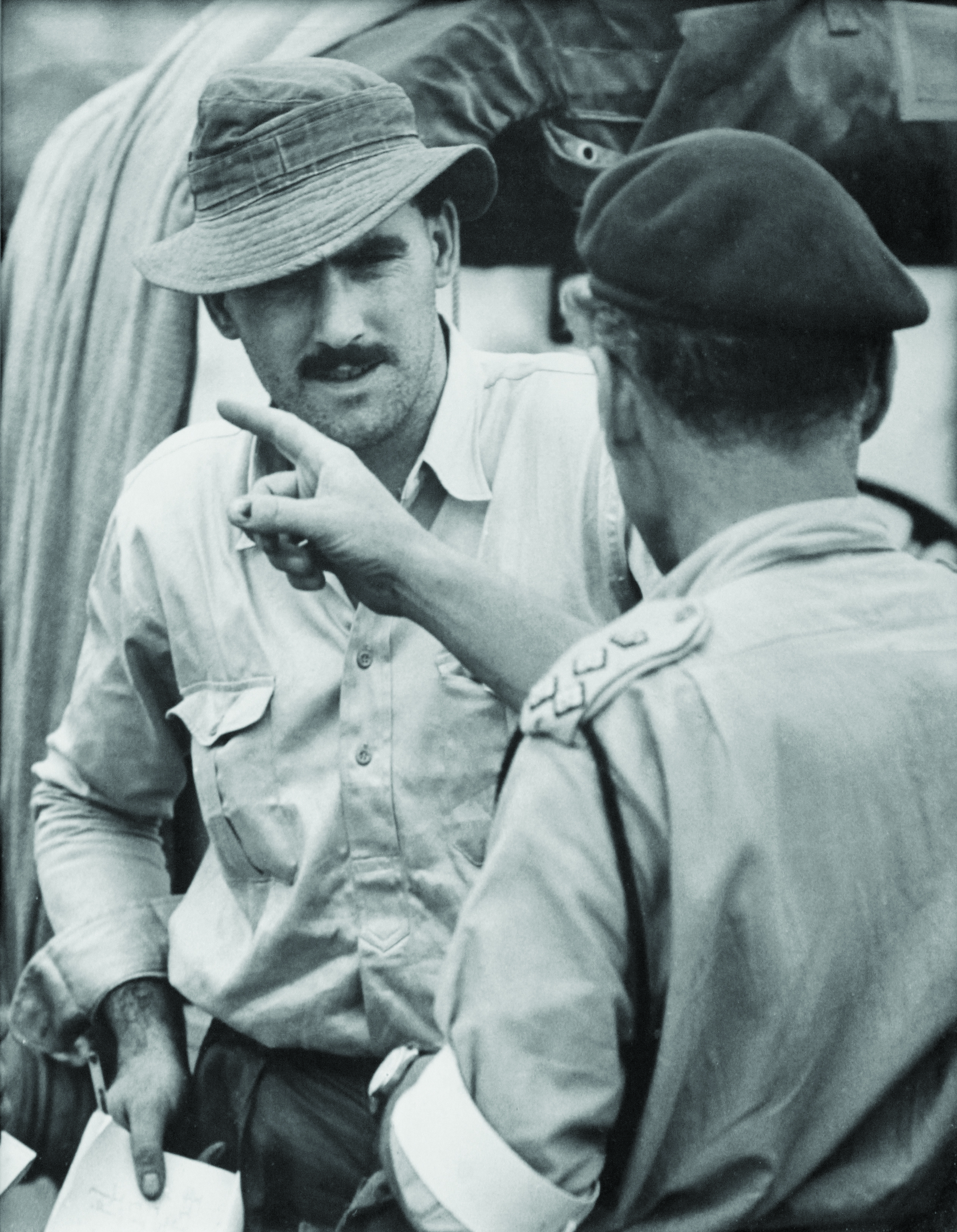

He joined the Royal Artillery and was posted to Hong Kong, gaining his officer’s commission along the way. On returning to Scotland he was looking for something new and exciting to do, and an advert in a newspaper provided the answer.

“Young man of sound education wanted for training as newspaper reporter, Box 127,” it read. He applied and landed the role at the Glasgow office of The Sunday Post, earning £7 a week . . . and the rest is history.

As a young reporter he was to became the paper’s first HON Man (HON stands for Holiday On Nothing)– a much-loved recurring feature that ran for years.

In God Bless Mrs McGinty! he explains how the idea came about.

“It all started in a Dundee tearoom where my predecessor – John Martin – was fussing over a lightly poached egg on toast when the conversation turned to holidays, which the harassed waitress obviously overheard. For, looking at JBM’s tanner tip, she said ‘You can’t have a holiday on nothing, you know.’

“JBM did not increase the tip. He just said ‘That’s a good idea,’ and the HON Man was born.”

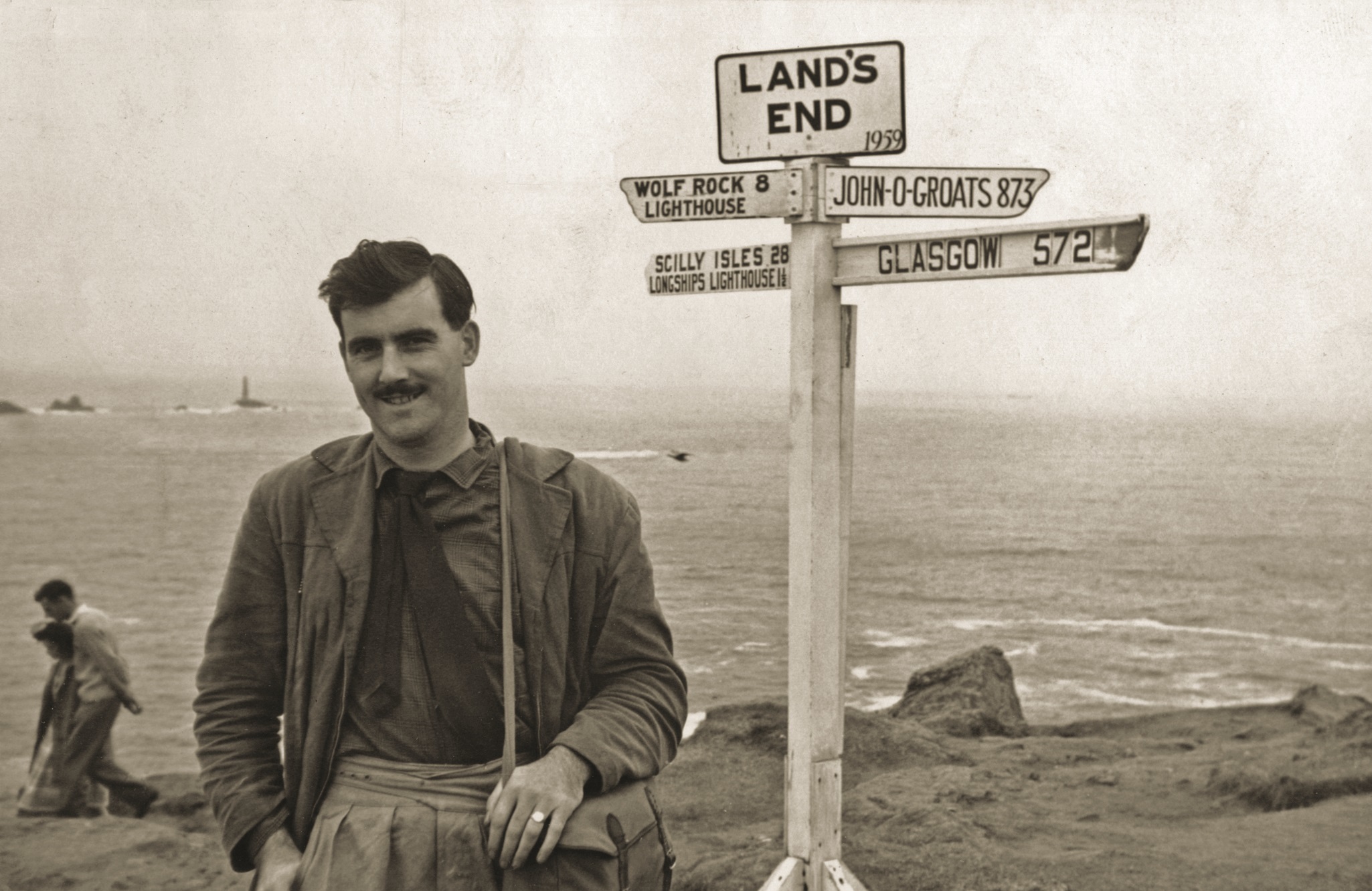

As HON, Bill did everything and went everywhere.

He was a ballet dancer, a Sotheby’s auctioneer, advance manager for The Beatles, a private detective, a lay preacher and a salmon poacher.

He travelled the world on every form of transport, from scooter, camel and rickshaw to yak, ambulance and Rolls Royce.

As he wrote: “I needed so many visas that I ran through passports like weekly season tickets for the train. Wherever you put your finger on a globe of the world, chances are I’ve been there.”

He ended up in some far-flung places.

“An outboard-rigged canoe took me deep into the hinterland of Thailand to the Temple of the Storks at Wat Phai Lom, to see the same storks that emigrate to the roofs of Dutch villages.

“A thing of beauty on a birth congratulations card, these storks were the dirtiest, noisiest, greediest birds in the world.

“I was more intrigued by the ancient Buddhist monk at the temple who knew every Burns poem by heart and could recite them in an extraordinary oriental English with a Scots burr.

“Some wandering Scot in the late 19th century had left a ‘complete works’ in gratitude for the monks treating his wounds. The sage had made a life’s study of the volume as a ‘devotion’.”

He was also on the first post-war passenger train allowing tourists into Russia – to find himself accompanied all the way from the Hook of Holland to Moscow by a certain Russian Colonel F, who just happened to be on leave from his job as ‘a military attaché’ at the Hague.

Bill wrote: “The first thing he did was steal the list of useful Moscow telephone numbers I had acquired (since there were no telephone directories available to any such as myself who entered the Kremlin’s ken).”

It was an exciting gig, but tough, as Bill reveals.

“It was no picnic. On a three-week trip to New York, I lost more than a stone in weight, rushing to cram in a packed schedule of assignments from lift operator in the Empire State Building to exclusive interviews with Jack Dempsey and Perry Como – all on hamburgers, coffee and three hours sleep a night.”

Though he was a hit as a globe-trotting reporter, it was clear Bill was destined for bigger things. In 1968, at just 34, he was appointed editor of The Sunday Post.

He quickly developed a reputation for being a fearsome boss. Bill himself acknowledges as much in his book.

“When the paper was going well, I contented myself by playing the part of the caged Russian bear, cuddly from a distance, but dangerous if you wandered too close.

“But when the paper ran into a rut, I became as silent and still as a boa constrictor, withdrawing into my own coils until I had decided where and when to strike.”

Maggie, who met him in 1987 when she became editor of the Sunday Post Magazine, remembers well his daunting demeanour.

“He was scary, but he was very fair. He would give you a real tongue-lashing if you did something wrong, but then it was all over and done with . . . as long as you learned the lesson and didn’t repeat that mistake!”

But then she smiles.

“He was a big teddy bear really, though.”

He may have had a soft heart, but it was his sharp brain that brought success.

“Bill lived the Sunday Post,” says Maggie. “He was thinking all the time about it, about how to make it better. His whole life was the Sunday Post.”

He was the perfect fit for the Post. He knew what made it tick – knew that people, real people, were at its core.

“He loved nothing better than people,” says Maggie. “He found them endlessly fascinating and anywhere we were out he would engage folk in conversation.

“I remember one day we were in a cafe having a coffee and a young couple came in with a baby. We both thought they looked like they were struggling a wee bit, so before we left Bill put a £10 note down on the table and said, ‘It’s nearly Christmas, buy something for the baby’. He would do things like that, but he didn’t shout about it.”

Bill died on February 2, 2012, aged 77.

When Maggie talks about that time it’s with sadness, of course, but also pride for the character of the man she loved.

“Right up until the end Bill had tremendous spirit. He never once felt sorry for himself.”

It was two years later that she opened that desk drawer and found those folders – one pink, one blue.

Maggie says: “I do hope people enjoy the book – though it’s really for the family more than anything else. It’s a kind of legacy I suppose.”

A legacy that Bill, no doubt, would be proud to see in the hands of his beloved Sunday Post readers.

Maggie is talking about God Bless Mrs McGinty! at the Aye Write book festival in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library at 7.30pm on Friday, March 11. The book will be published on March 1 by Waverley Books, price £9.99. Order through your local bookshop.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe