Famous for its many changes, for rain at any time of year and even occasionally surprising us by becoming sunny, the British weather really is special.

Comedian Billy Connolly once summed it up, saying that when he brought his Australian-raised kids back to Blighty, they asked: “Dad, why is the sky so low?”

Yes, it does tend to get a tad grey and miserable at times but at least our grey skies give us something to talk about.

Bristol-born, but based in Sevenoaks, Kent, author Patrick Nobbs has meticulously researched the history of our weather, and written a book about it.

And if you think some of the freak weather we’ve seen in recent years was special, you ought to read some of the tales of British weather in days gone by.

“Depending on which part of the UK you’re from, we get every type of weather imaginable,” says Patrick.

“It’s an easy ice-breaker when we talk to people, because there is always something happening, whether it’s good or awful.

“The people I always feel slightly sorry for are the weather men and women on the TV breakfast shows. If there’s a blizzard, he or she and the camera crew get sent outdoors at the crack of dawn.

“There was an incident recently when a woman was doing a weather report close to the waves, and she got hit by a fish.

“This massive fish, I think it looked like a plaice, came flying over and hit her on the head!”

So this would explain why we Britons discuss the weather so much. But what do the natives of sun-baked Spain, or France, or anywhere but Britain, talk about?

“They talk about it, too!” Patrick points out. “It’s just that they have a lot of sunshine in the South of France, for instance, but with the very strong wind, the Mistral, to spoil things.

“They can get hurricane-force winds that drive fires, so you can see how everywhere has its own weather thing.

“OK, in Spain, you may just say: ‘It’s hot again today’ three hundred times, but every place has its weather foibles.”

Perhaps we’d like to swap our grey days for those sun-kissed ones our Continental cousins enjoy, but Patrick points out that, in Britain, at least we get some real variety.

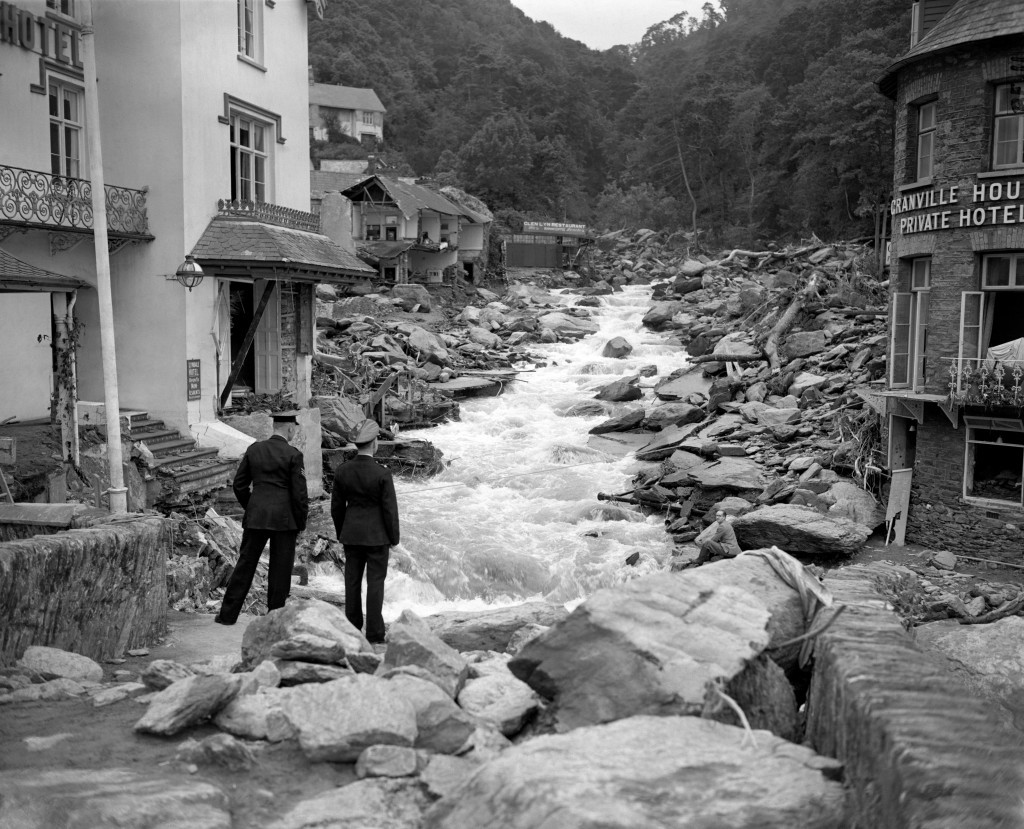

It’s when he mentions a tsunami hitting Bristol, or a tornado tearing through Leighton Buzzard, that you realise just how much variety.

“I have a section in my book called Unusual Events, and one was in 1783, following a massive volcanic eruption in Iceland. It covered Britain in a cloud of sulphur, killing 70,000 people in Europe.

“Tens of thousands died in Britain, because all the vegetation turned black and the crops failed.”

Scotland was under that cloud for eight months.

“There was a huge avalanche in Southern England in 1836, killing 15 people. The Fire of London is also considered a weather event, and there was a very strong gale that picked up all the sparks — everything was made of wood — and it spread east.

“There was a very severe gale in the Bristol Channel, and if it had hit that part of England and South Wales today, it would have killed well over a million people.

“That was in 1607, and about 1,500 were killed. Though it’s not well-known, that was one of the worst things that’s happened in terms of weather disasters in that era.”

With all this knowledge, Patrick must be just the man to ask about our future. Following horrendous floods and other extreme conditions in recent years, should we be terrified?

And where should we build our houses if we want to be safe from the weather?

“We have already seen that worse weather is creeping up on us,” he admits. “I am in my mid-40s and I have seen the weather change distinctly in my lifetime.

“There are a lot more extremes, and as the climate has begun to warm, the jetstream is buckling in more extreme ways.

“In the US, you’d expect there to be real heat, and they have had severe droughts.

“But that means you’ll also have extreme winters, and in places like Boston, they have had minus-20 temperatures. The impact of global warming can be wildly different in different places.

“In the UK, that same winter of the US drought, we got Southern England having gales almost every day, to the point we were being hit by lightning. You’d find trains to work cancelled, with trees down on the lines, and it was just three months of rain.

“We got more rain — 1,000 millimetres — than you normally get in three or four years. These are the types of change we are going to see.

“It will be cycles of more prolonged extreme weather, and in areas like the Lake District, Lowland Scotland and South-West and Eastern England, all will suffer from different types of flooding.

“More will need to be invested to protect us against flooding. The other thing that hasn’t happened for a while is droughts, which we haven’t really suffered since the 1990s and early 2000s.

“The whole of the UK suffered, but since then, we have been out of that cycle.

“When it returns, however, it will be more prolonged, more severe.

“So if I was building a house now, London is the last place I’d go, as it is low-lying. I would build it as high as I could go, on top of a hill, in the middle of the country.

“If you have a sturdy mansion, windproof, high enough above the flooded areas, and you have a steady supply of drinking water, you’re sorted!”

One hope, perhaps, is that our brainy boffins come up with some invention that can alter weather conditions.

And blasting the clouds away, to let the sunshine through, must be possible, too, don’t you think? Or hitting them with chemicals to produce rain when needed?

“There was a lot of activity in the 1950s,” Patrick recalls, “when they fired silver iodine into the clouds, the idea being to shatter cloud crystals, creating disturbance.

“This can create rain, but only on a very small scale. Droughts tend to be on a much- larger scale, and I think people have kind of given up on the idea.”

But there’s one thing we’ll never give up on — talking about the weather!

Patrick Nobbs’ book, The Story Of The British And Their Weather: From Frost Fairs To Indian Summers, is published by Amberley, priced £8.99, ISBN No 9781445655444.

READ MORE

Veteran weatherman Mervyn warns there are more storms to come

My Favourite Holiday: Weatherman Christopher Blanchett loves iconic Sydney

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe