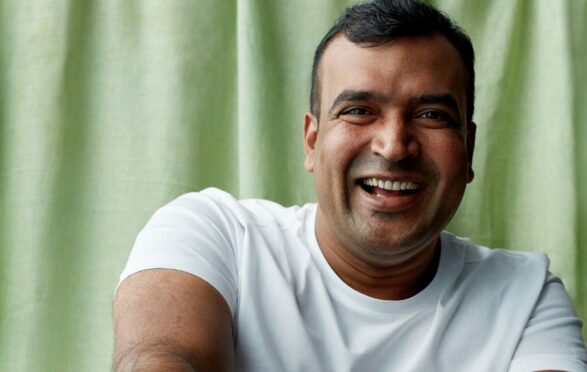

For many viewers it was Santosh Shah who first introduced them to Nepalese food on MasterChef: The Professionals 2020. But, despite being from Nepal, he had only recently discovered more about the food of his home country himself.

Having left his village of Karjanha and family at just 14 to move to India and work as a kitchen porter, he progressed to chef, and Indian food was what he cooked – and what he knew – for 20 years.

Before his stint on MasterChef, he began to research the cooking techniques and produce of Nepal, and the experience proved something of a homecoming: a return to the food he cooked with his mother as a child.

“I was so amazed with the cooking and food we have… from the fermentation to pickling, the dumplings, the bread, high-altitude food, low-altitude food, fire cooking, lots of meat, lots of fish,” he says. “I’m thinking, why didn’t I do this before?”

He is now on a mission to “contribute Nepalese food to the world” via his debut cookbook, Ayla, and plans to open a fine dining Nepali restaurant in London.

There’s a misunderstanding, he says, that Nepalese food is very similar to Indian, which borders three sides of the country.

He explains: “It’s totally different. India is such a big country – even one state is bigger than Nepal and if you’re a small country next to a big country, you’re always going to be subject to their stature.”

Of course, some influence does come from its neighbours, which also include China (the Tibet region borders the north side of Nepal), Pakistan, Burma and Bhutan, Shah explains. But the secret is really in Nepal’s unique geography and biodiversity.

He says: “Where I come from, the Siraha region, it would be 25C now, and if I travelled north 100km, it would be minus (temperatures). So you can imagine, 100km from every part of Nepal, what food is growing, the vegetables, the meat, everything is changed.”

From the arid high altitudes of the Himalayas, to the band of rich green valleys and rivers, and the tropical grasslands of Terai in the south, the crops and livestock farmed are diverse.

But whether it’s street food like kukhura ko momo (steamed chicken mo mo dumplings) or festival specialities like terai malpua ra rabri (syrupy pancakes with saffron creamy milk), you can be sure of the sophisticated use of spices.

And while his book celebrates the wild boar, buffalo meat and jungle fowl that’s so crucial to Nepali cuisine, they can all be substituted for easier-to-source meats, he says.

Fermentation, pickling and sun-drying, meanwhile, are processes borne out of necessity in Nepal. “Even in my village, 10 or 11 years ago, they didn’t have electricity, so we didn’t have a freezer to keep anything in,” Shah explains. It’s also important during monsoons, which can have a devastating effect on agriculture in the south. Gundruk, made using mustard leaves, is the country’s most famous preserve, and you’ll find it dotted through Shah’s recipes.

Shah has come a long way from his early childhood in Karjanha. “When I was young, everybody had to cook at home. I’m from a very poor family background, we had one big room, there was a kitchen in a corner, in another corner there was a bed,” he says. But there was a lot of people in that one space – Shah is the youngest of seven siblings. “I have five brothers and two sisters; when everybody got married and left the village, my mother was there cooking and I was always next to her, she’d say,‘Cut this one, cut that one’.

“In Nepal, if you are poor then you have a vegetable garden. Rich people buy from the market, poor people grow their own. So we had everything in our garden.”

After finishing school at 14, he didn’t have the money to go any further in education, heading for the bright lights of India instead. After six months, he asked the head chef for a chance to cook and that’s when his culinary journey really took off – moving to the UK in 2011, where one of his first jobs was at Brasserie Blanc, owned by Raymond Blanc, before working at Michelin-starred Benares, becoming head chef at Cinnamon Kitchen and executive chef at the five-star LaLit Hotel in London.

“I love cooking. Apart from cooking, I don’t know anything,” he says, with that jolly laugh you can’t mistake.

Santosh Shah’s Thukpa: Sherpa noodle soup

Thukpa is a soup shared by both the Nepali and Tibetan Sherpa communities. “To handle the freezing winters in high altitude, their diet is heavily based on carbohydrates,” explains Shah. “The soup is laced with the uplifting warmth of cumin, turmeric and timmur peppercorns. Some cooks add cornflour to thicken the soup, but I prefer a thinner broth with my noodles.”

Serves: 4

You’ll need

- 100g soba noodles, or egg noodles

- 3tbsp vegetable oil

- ½tsp hing (asafoetida)

- 300g free-range chicken breast, finely chopped

- ½tsp ground turmeric

- 50g finely chopped carrots

- 180g finely chopped mixed peppers

- 50g thinly sliced green French beans

- 80g finely shredded white cabbage

- 1tsp salt

- 800ml chicken stock

- 2tbsp fresh coriander, chopped

- 1 lemon, quartered, to serve (optional)

For the spice paste:

- 1 large garlic clove

- 4tsp finely chopped fresh ginger

- 4 fresh green chillies, roughly chopped

- ½tbsp cumin seeds, dry roasted

- 5 Sichuan peppercorns or timmur peppercorns (timmur is native to Nepal and is a cousin of the Sichuan peppercorn)

- ¼tsp black peppercorns

- 1tbsp fresh coriander, chopped

- 1 small tomato, deseeded and chopped

Method

Start by making the spice paste. Place all the ingredients for the spice paste except the tomato in a small food processor or electric spice grinder. Blend until you get a paste. Add the chopped tomato and blend again. You should get a smooth, spoonable paste. You can make this paste in advance and keep it in the fridge for two to three days, or in the freezer for one month.

Cook the noodles according to the packet instructions and set aside.

Heat the oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Stir in the hing and cook for a few seconds. Add the chicken and cook for five minutes, until slightly golden. Add the turmeric and cook for one minute.

Add all the vegetables and stir-fry for a couple of minutes. Stir in the salt and spice paste until all the ingredients are well coated. Cook for a couple of minutes.

Pour in the chicken stock, bring to the boil, reduce the heat and simmer for five minutes. Add the noodles and cook for a couple of minutes, just enough to reheat them.

Adjust the seasoning to taste, add the chopped coriander and serve with lemon quarters for squeezing over.

Ayla: A Feast Of Nepali Dishes From Terai, Hills And The Himalayas by Santosh Shah is published by DK, priced £20. Available now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe