In a country where the weather changes by the hour, perhaps it is no surprise we talk about it so much.

Whether it is with lifelong pals or perfect strangers, what’s happening up in the sky is our favourite topic of conversation – which means we need lots of descriptive words for the most common type of weather that we experience: rain.

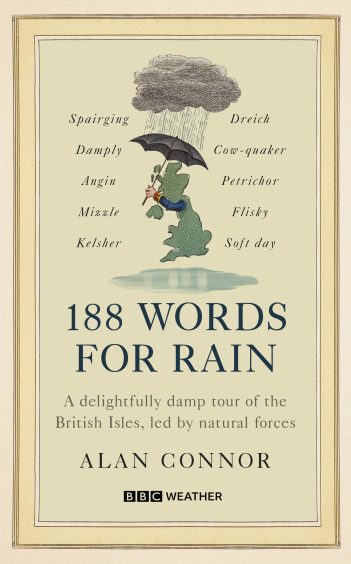

Be it mizzle or dreich, a thunnerplump or spairging, there are hundreds of terms to describe the wet stuff, with each region having its own rain vocabulary.

188 Words For Rain

In new book 188 Words For Rain, writer Alan Connor picks out his favourites from around the British Isles, digging into their meanings and quirky histories. A large proportion, unsurprisingly, are from Scotland.

“People from other parts of the world don’t really understand why we talk about it so much,” he said. “But in most places, tomorrow’s weather will be pretty much like today’s and will stay the same throughout the day. I think it’s the unpredictability that makes us talk about it.

“As I understand it, Japan is the only other place like us – being an island between a big continent and a big ocean – so they also have these completely different weather systems bashing into each other.

“I think cold temperatures and a horrible wind upsets people more than the rain, but when we’re having a moan, rain becomes shorthand for terrible weather.”

Alan, who grew up in Edinburgh, started to think about our relationship with rain during Covid. Like many, he and his family switched to UK-based holidays during that time and it was on those staycations when he noticed the many different rain phrases around the British Isles.

“Many of these words have a nice sound to them, quite affectionate words, like mizzle [a mist that is apt to turn to drizzle],” he continued. “There is something inherently amusing, or even romantic sometimes, about rain that you won’t find about wind, for example. It’s a weather that stirs the emotions. There is lots of romantic kissing in the rain in movies and lots of songs about being sad in the rain in a way there isn’t about the baking heat or a great big gale.

“When I think of Spider-Man upside down and having that kiss, that would be horrible in a hot New York summer or if they were being blown around.

“Rain stimulates all the senses and I think it can make you feel alive. That’s why I zeroed in on it for the book.”

Alan’s favourites

Alan, also a screenwriter and crossword setter, has lots of favourite Scottish rain words.

He said: “I had to laugh at atween wadders [a dry day following a wet storm, with another due imminently] and to use the word weather to mean a rainstorm is very Scottish.

“I like Ug, a short form of ugly, because everyone knows what you mean by that, and blashed – a battering rain – is great because you can tell what it means without anyone having to tell you.

“Another I like is haizer – to dry up after the rain, and clothes can also haizer. I love the sound of glashtrochie, which means filled with continuous rain.

“I find that expat Scots in England love to share the word dreich and they are right to. The word seems to disappear quickly after crossing the border south, but it does creep up when people are asked for their favourite Scottish word.”

Although mizzle is an ancient word, it was given a mainstream platform by weatherman Francis Wilson when he joined the BBC Breakfast team in 1983. He gave forecasts in a new way – not only were the weather symbols computer generated rather than magnetic clouds, but he also brought a less formal set of words to describe the weather.

His influence was an example of the changing way we look at the weather, something that has continued as technology and forecasting have advanced. With weather apps on our smartphones, we have more information than ever before, which only increases the conversation.

Alan said: “It used to be that forecasts were pretty accurate for the next day or two and then they weren’t sure what would come in, whereas now the details we receive means there is no excuse for moaning about getting wet, because these apps will tell us how likely it is to be raining for each hour of the day.”

Notable moments

Alan looks at other notable Scottish weather-related moments in history, such as Charles Macintosh taking a volatile chemical called naphtha and inventing the raincoat.

He also shines a light on Robert Angus Smith, a Glaswegian who joined the chemical laboratory at the Royal Manchester Institute and wrote a book, Air And Rain: The Beginnings Of A Chemical Climatology, in 1841 in which he coined the term acid rain. It was a phrase that entered the mainstream more than a century later, in the 1970s and 80s.

“I don’t think we’ve celebrated that we beat acid rain,” Alan said. “It was something talked about a lot in the 80s and was a genuine problem, but by working together with folk around the world, it stopped and some of the forests have grown back their green and some of the moss has returned to the hillsides.

“That’s something we should be aware of, because when we look at the warm wet winters we’re getting now, it’s possible to become very resigned and apocalyptic about it and feel helpless, but I think the acid rain story is a reminder that we can get happy endings.”

Alan doesn’t believe we will ever tire of talking about it.

“Talking about the weather enables you to speak about whatever you want,” he added. “If you say the garden needed it, it allows you to begin talking about your garden. Or if you say you hope it clears up for the weekend, it lets you start talking about your plans. We all live in weather, so really we can use it to talk about anything that matters to us.”

188 Words For Rain by Alan Connor, a BBC Weather book published by Penguin, out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Jochen Braun

© Jochen Braun