It’s 50 years this month since the giant concert that changed the course of rock music.

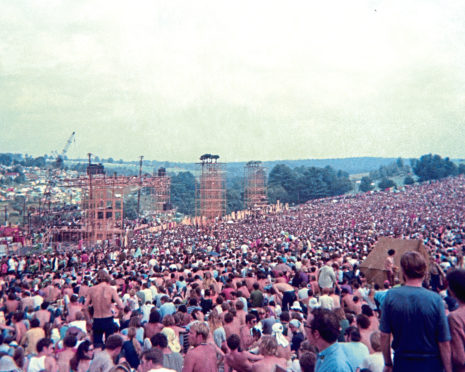

Woodstock, which saw over 400,000 music fans descend on a large dairy farm close to Bethel, New York, made a whole generation feel they were part of a movement, rather than just lots of people who liked similar music.

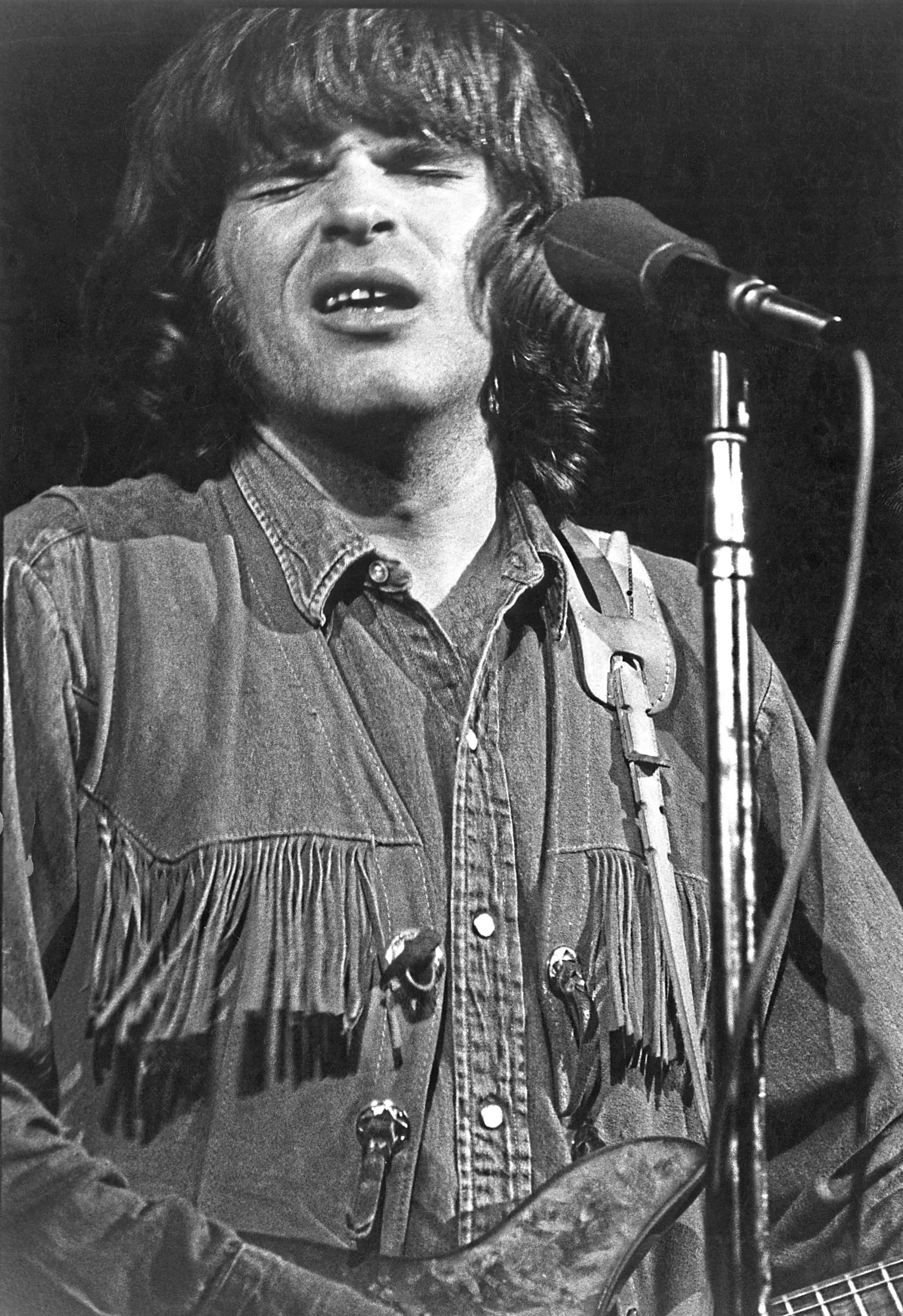

The whole thing had been the brainchild of a small group of New York entrepreneurs, and Creedence Clearwater Revival went into the history books as the first big name to sign up for it.

“Once Creedence signed, everyone else jumped in line and all the other big acts came on,” said their drummer, Doug Clifford.

Alas, it didn’t go as smoothly as that – his band were left fuming after having to start their set at three in the morning and even being left out of the Woodstock movie, at the insistence of their leader, John Fogerty.

“We were ready to rock out and we waited and waited and finally it was our turn,” Fogerty recalled ruefully. “There were a half-million people asleep.”

Bad Moon Rising, indeed.

“These people were out. It was sort of like a painting of a Dante scene, just bodies from hell, all intertwined and asleep, covered with mud.”

One guy far from the stage lit his cigarette lighter and cried, “Don’t worry about it, John, we’re with you!”

Fogerty joked that they played the whole show for that one wide-awake Creedence fan.

That wasn’t the only setback along the way – you couldn’t fit every top singer or band on the bill, and besides, some couldn’t or wouldn’t appear, anyway.

One notable absentee was Bob Dylan, who lived and even recorded in the Woodstock area. Some reckon the folk-rock god looked out his window, saw hundreds of thousands of hippies, and decided to go off on holiday far, far away.

Mick Jagger, meantime, was Down Under making the ill-fated Ned Kelly movie, so that meant the Stones couldn’t appear either.

Over a weekend where the rain occasionally threatened to ruin things, 32 acts did their stuff, much of it captured on live albums and the movie that followed.

Joni Mitchell, who had been left in tears by nasty fans at a recent gig, didn’t play but wrote a classic song about it, simply entitled Woodstock, which would become a hit for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and again for Matthews Southern Comfort.

Speaking of CSNY, they really were a supergroup, and would prove it, even if this was right at the start of their lives together.

Four superstars in their own right, all with fantastic singing and guitar-playing credentials, on paper it looked as if they would produce special music if brought together.

Stephen Stills told the vast crowd: “This is the second time we’ve ever played in front of people, man. We’re scared!”

Graham Nash had already been a huge star with The Hollies. Stills had well and truly established himself, too, alongside Neil Young in Buffalo Springfield.

And David Crosby had been a feature of five Byrds classic albums and also done his business with Buffalo Springfield.

As the four of them would do throughout their careers, solo or together, they brought a mixture of acoustic songs and harder electric ones.

Three Augusts earlier, another band had played their final concert in the USA, or anywhere else, at Candlestick Park, San Francisco.

Surely, though, the chance to ally themselves with all the bands already booked, and the opportunity to be the headline act in front of more than 400,000, would be deeply tempting?

Not so for John Lennon, who is said to have demanded that a slot also be found for Yoko Ono’s Plastic Band.

That, however, is just one angle – others have claimed that Lennon fancied doing it, Yoko or no Yoko, but couldn’t get back into the United States from Canada because Richard Nixon really didn’t like him very much.

We’ll never know, but it’s intriguing to think about what a successful Woodstock might have done for the Fabs. Perhaps doing huge concerts might have brought them closer again and stopped them breaking up soon after?

As for The Doors, hugely successful at that time, drummer John Densmore can be seen at the side of the stage during Joe Cocker’s astonishing set, but singer Jim Morrison is thought to have hated singing at outdoors concerts and said no, thanks.

Free decided it would be anything but All Right Now and turned it down, too, whereas some said no and were left kicking themselves for years to come – such as Tommy James and the Shondells.

Tommy later described how his secretary had said: “There’s this pig farmer in upstate New York that wants you to play in his field.”

Described like that, you can see why they turned it down. We wonder how long that secretary kept his or her job, though.

It may have gone down in folklore as a hippie festival, but it certainly wasn’t intended as something for nothing.

Woodstock was very much about profit-making, and almost 200,000 tickets were sold well in advance. It was only when hundreds of thousands more people turned up than anticipated that they simply gave in and let many in for free.

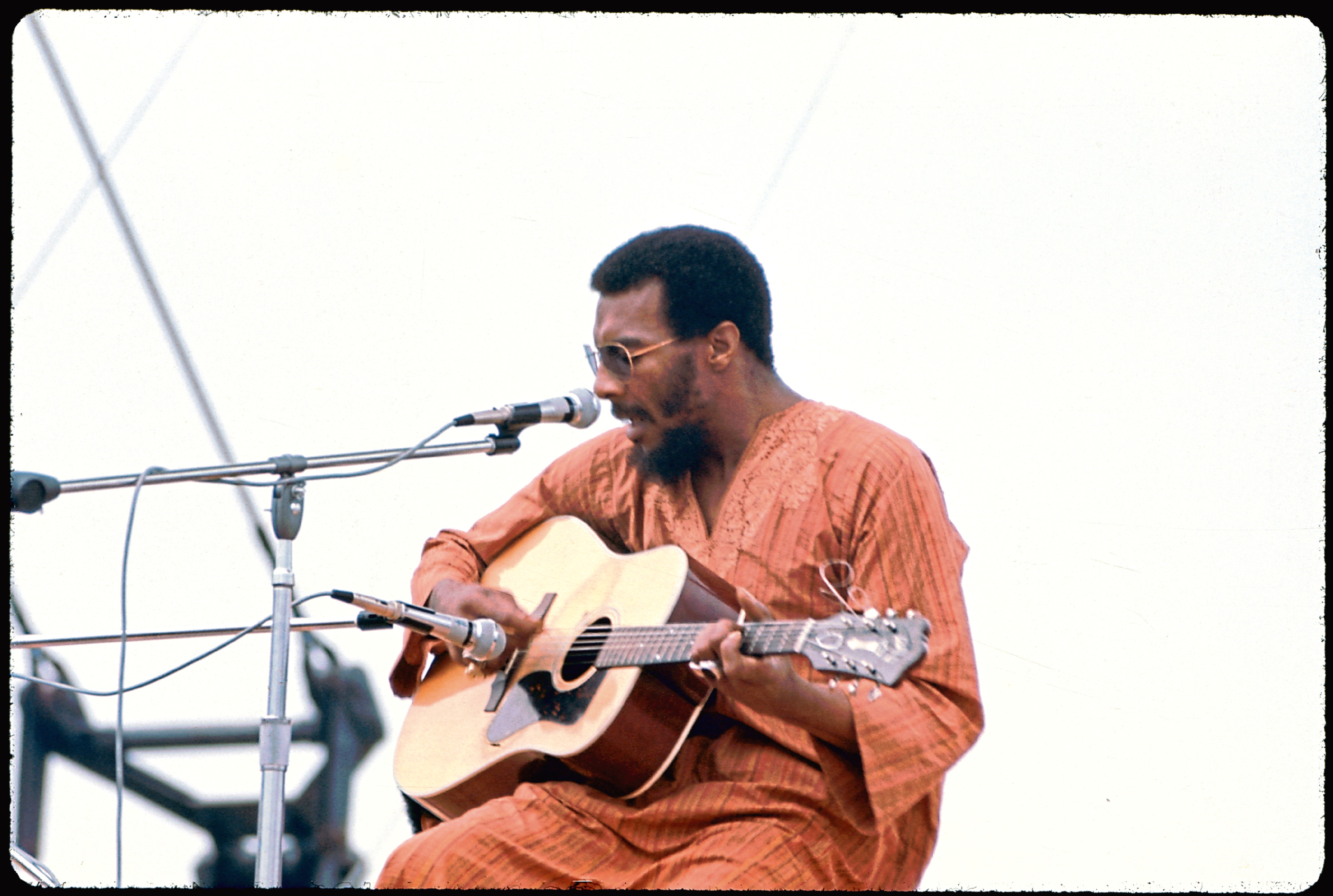

Those who arrived in time for the very start would have seen Richie Havens – a lot of Richie Havens.

He had already played for two hours when they told him that there were problems backstage, and to just keep going.

“I’d already played every song I knew and was stalling, asking for more guitar and microphone, trying to think of something else to play,” he would say.

It was the making of him, and a man who had been little-known before became an instant star.

Havens, who would have hits with covers of Beatles tracks like Here Comes The Sun and Lady Madonna, went on to have a great career, often just him alone with an acoustic guitar.

He passed away in 2013, aged 72, having become one of the strongest Woodstock memories for many, simply because he held the attention of hundreds of thousands for nearly three hours, making it all up as he went along.

With Hare Krishna emblazoned across the front of the stage, Swami Satchidananda then climbed up to make an opening speech and invocation.

The Indian teacher and spiritual master’s prayer for peace and love, with fans sitting peacefully as far as you could see into the distance, was an incredible moment.

He really set the tone for a weekend of peaceful music and friendship, and the amazing thing about how he calmed so many excited fans was that he was convinced to do it while they were panicking backstage about what might happen next!

Tim Hardin is another who would die young, but one of the true giants of Woodstock.

Hardin was the man who gave us classics like If I Were A Carpenter and Reason To Believe, his songs covered by everyone from Rod Stewart to Johnny Cash, The Carpenters to Bobby Darin.

His heroin addiction would kill him before he was 40, and none of his Woodstock performance is in the movie. If you find it on YouTube, you’ll wonder why on Earth not.

Ravi Shankar then played despite the rain coming, but found he didn’t particularly like the event. He would soon criticise the hippie movement and especially the drug culture that grew up around it.

“It makes me feel rather hurt when I see the association of drugs with our music,” he said. “The music to us is religion, the quickest way to reach godliness.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Tucker Ranson/Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images

© Tucker Ranson/Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images © Ralph Ackerman/Getty Images

© Ralph Ackerman/Getty Images