It is a literary journey spanning 130 years, two oceans, and a meeting with the great-granddaughter of one of the world’s most famous artists.

Devika Ponnambalam’s debut novel I Am Not Your Eve, a reimagining of the life of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian child bride, will on Thursday be among six in the running for the first book award at Scotland’s National Book Awards.

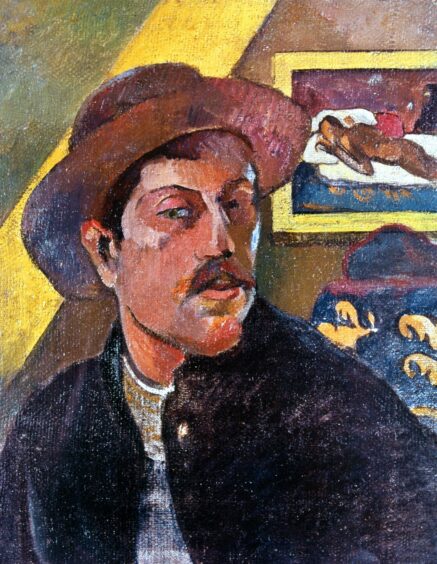

Finally giving a voice to the artist’s “wife” Teha’amana, who was said to be 14 but may have been only 11 when he met her in 1891, entwined with the myths and legends of the South Pacific islands, the book’s inspiration came 25 years ago in a picture in a magazine article on the life and work of the Post-Impressionist artist.

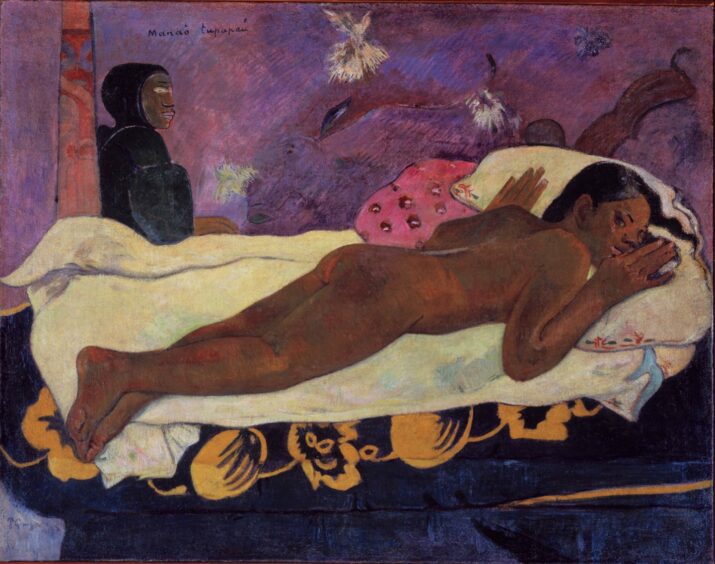

As Ponnambalam gazed at Gauguin’s 1892 masterpiece The Spirit Of The Dead Keeps Watch, she was arrested by the vulnerability of the child lying naked on a bed. She was Teha’amana, painted by the French artist who travelled to Tahiti believing it was a paradise unspoiled by civilisation.

The author said: “The picture was small but I was dumbstruck. I felt an instant connection. I carried on reading the article about Gauguin going to the South Seas leaving his family – including his 14-year-old daughter who was his favourite child. Teha’amana was mentioned only briefly. Gauguin had called her Tehura in Noa Noa, his fictional account of his trip to Tahiti. He told how she became his wife, and taught him about the stars, and myths and legends.

“She was the young girl he took as his lover. He said she was 14. I believe she was 11. She was the first. But no one spoke about her or about the women who came after. I was haunted by her.

“Her story had been completely ignored. I was surprised no one had questioned it in all these years. It was so dark, so unjust.”

There are conflicting reports of what happened to the artist’s model and “bride”. Some say she became pregnant, gave birth and died when he abandoned her, others say that when the artist left she married again and had children. But sources on the island told Ponnambalam she was 11 when Gauguin married her and died of syphilis without having children.

It took a master’s degree in creative writing, a move to Scotland, and a stay in Tahiti to interview Gauguin’s great-grandaughter before Ponnambalam could finally find Teha’amana’s voice.

Of her pride at making the Scotland’s National Book Awards’ first book shortlist, Ponnambalam said: “Teha’amana’s story is unique and, until now, untold.

“This is the song of the silenced, the abused and the colonised. This nomination will hopefully take her story and that of her culture to many more readers.”

The author, 53, also an award-winning filmmaker, was born in Brunei, where her late father, Chidambaram Ponnambalam, was an English and history teacher. She moved to London when she was eight, her mother Sarojana, now 80, having already gone ahead to start a new life for the family. It was a difficult move marred by racism.

“It was the ’80s and ’90s when it was OK to be abused in the street for the colour of your skin, it was not a hate crime then,” she remembered. “I’d wanted to tell stories from when I was 16. That led me to the National Film and Television School.

“But I found the industry very difficult as a brown woman and the TV industry seemed to me both racist and sexist. I managed but I realised the only way I could control the stories I wanted to tell, was to write.”

In 2003, the year of her father’s death and the centenary of Gauguin’s birth, she signed up to a creative writing course at the University of East Anglia. “I started off wanting to tell my own story but I found it too difficult to do. And in the back of my head was this other story, this painting.

“I saw her and I could see so much of myself. I felt connected to her as a brown woman; this girl lying on a bed, vulnerable through artist’s gaze. I thought I would try to tell her story.

“It was the right time to do it but there was so much research to do and it was a whole different culture and a whole different time. I was working nine to five in London to make ends meet and doing research in the evenings but getting nowhere. It was only when I came to Scotland that everything came together and I finished writing the book.”

After a move to Edinburgh in 2017, she applied for and received a grant from Creative Scotland that enabled her for the first time to conduct research in Tahiti and spent a month there in 2018.

“I had been dreaming about it for 10 years but I had never had the money to go there. One of my guides was Tahitian and said he knew Gauguin’s great-granddaughter Isabelle from his second mistress Pau’ura who is in his painting Nevermore. On the day I met her at her house I was nervous but she was warm and generous.

“She read my Tarot and said the book would be written, would do well and I would come back to Tahiti. Isabelle is proud of Gauguin and her bloodline even though she lives modestly and has seen nothing of the billions from sale of his paintings.”

On the penultimate day of her research trip, during a traditional ceremony on ancient sacred ground, the unexpected happened. She revealed: “I met a Tahitian priest on Marae Arahurahu – an ancient place of worship. He’d been informed by my Tahitian guide that I was trying to find out about the girl who’d been Gauguin’s first ‘wife’. The priest suddenly turned to me and asked, ‘what do you want to know about Teha’amana?’

“I said I wanted to know what happened to her and he told me she died of syphilis. She was 11 years old. I was broken and I cried. I remembered what I had felt in the 1990s when I first saw her image and wondered if she had contracted syphilis. It was a deeply spiritual moment. A culmination of that whole journey that brought me to Tahiti and to the Marae.

“He said that after Teha’amana’s death the family hid it all and she was buried secretly in the village. I decided to take that away with me and tell my version of the truth.

“Writing my first book when the subject matter was so weighty, and so far removed from my own culture and experience, was overwhelming at times, and probably why it took me so long. I think I was meant to come to Scotland to finish my quest here.

“Would I do Teha’amana and the history of her island justice? I hope she would be pleased her story has been told. I hope she would feel a sense of peace that at least she has a voice.”

The film

A 10 minute film, shot entirely on location in Tahiti by Graham Clark and edited in Edinburgh by Angela Leskovics, uses excerpts of the book’s narrative as a voice-over threaded throughout.

Devika Ponnambalam met the girl in the film, Lanihei Tehiva, whilst out in Tahiti.

I Am Not Your Eve, by Devika Ponnambalam, is published by Bluemoose

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock