On October 30, 1964, news spread through Glasgow and beyond that one of the city’s most colourful and controversial eccentrics had died following a house fire at his lavish home on Great Western Road.

Albert Ernest Pickard – known for the six decades he had lived in the city as A.E. Pickard – was a sprightly 90-year-old when he perished, and despite being of an age when most folk would be long retired, he had continued to keep newspapermen on their toes well into his dotage.

Generations of Scots had grown up reading about the wacky publicity stunts of this Yorkshire-born showman who owned so much property in the city that he often said: “You could hardly throw a stone in Glasgow without hitting some of my buildings.”

The master-jester

Indeed, The Sunday Post was particularly fond of him, referring to him as a “master-jester” and “the great Pickard” when covering the story of the pyramidical air raid shelter he had designed – apparently, in all seriousness – in early 1939, as the country prepared for war.

An advert which he published around that time announced an auction – the selling of his Elephant cinema on Glasgow’s southside – to raise funds to finance “his latest patent ARP Bomb Proof Shelter, a Trip to the Moon, the Hitler Golf Course at Balfron, the Dicker Estate and his Golf Subscription to Whitecraigs.”

No doubt, had the auction been successful, Pickard would also have used the proceeds to purchase a new addition to his collection of brightly coloured large cars. For years he had been known as the first person in Glasgow to be booked for a parking offence after abandoning his vehicle on Platform 8 of Central Station so he wouldn’t miss his train. He is said to have paid his £1 fine using a £100 note. It may be an apocryphal story, but, given Pickard’s form, it doesn’t seem at all implausible.

By 1960, when he caused a road accident and was suspended from driving, he had 15 cars but was found to have never had a driving licence. His subsequent attempts to pass his test were regularly covered in the papers while he indignantly complained: “I’ve been driving since cars were invented.”

Another of his antics was his 1951 General Election campaign during which he described himself as “the Independent Millionaire Candidate for Maryhill,” with the campaign slogan “Make ‘em laugh”. He certainly did that when, wearing plus fours, a yellow shirt and a Harris tweed jacket, he told the press that he was the only “lovely” candidate in the race – and claimed that he was “the champion of the poor”.

While he was holding court in his committee rooms, crowds of locals were ogling his Rolls Royce, which was parked outside. Its bonnet bore the legend “cocktail bar” on one side, and “coffee percolator” on the other, while writing on the rear wing proclaimed that previous occupants included “William II, [George] Bernard Shaw, Il Duce, [David] Lloyd George, Hitler and Pickard A.E.”. Asked to which section of the electorate he would appeal, and from which source he expected his votes, he replied: “Why, I’ll vote for myself.”

On election morning, while most candidates were visiting the polling stations, 5ft 2in tall Pickard – nicknamed “the mighty atom” by the press – rose at his usual time and headed out for a round of golf, telling reporters: “I might not get a ticket to Westminster, but at least I’ll get a card – a score card.” He managed to notch up 356 votes; his golf score was not publicly recorded.

Less than a year earlier, when police forces up and down the land were searching for Scotland’s Stone of Destiny following its theft from Westminster Abbey, Pickard fashioned his own Stone of Destiny, using chicken wire and papier maché, and drove it around Glasgow in a box bearing the words “Hame again” and his name.

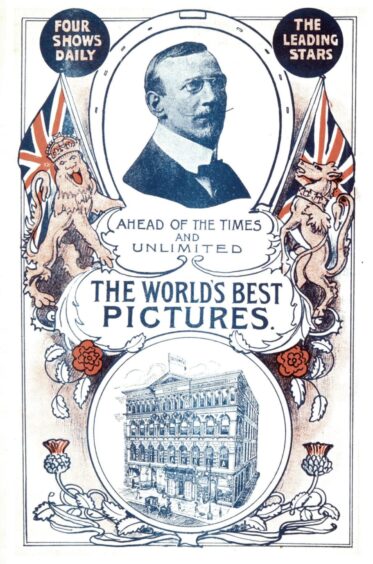

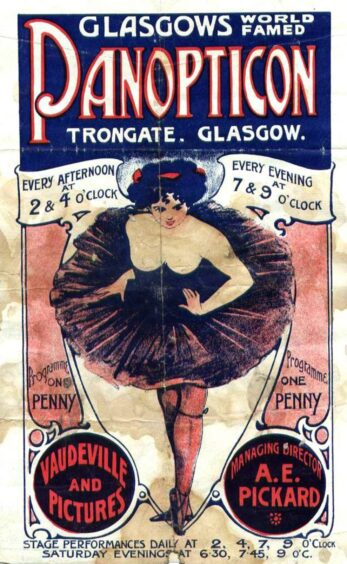

A wandering showman who had established amusement “resorts” in London at the turn of the century, he had come to Glasgow in 1904 and taken over the Fell’s Waxworks Museum at the Trongate, followed by its neighbour, the then run-down Britannia Music Hall. He refurbished it, rechristened it the Britannia Panopticon and made it a huge success. By 1909, he had added the Gaiety Theatre in Clydebank to his portfolio, which soon included picture houses across the city.

A trail of casualties

He may have seemed like a jolly joker, but A.E. Pickard left a trail of casualties in his wake. The self-proclaimed champion of the poor was said by his tenants to be a ruthless landlord. And that ruthlessness extended to his own family. Just four years before his death, The Sunday Post reported that he was suing his five children to regain control of 300 properties which he had bought in their names decades earlier.

The Tiger Tamer who pushed a wheelbarrow the length of Britain was the TikToker of Victorian times

Relationships with his offspring had deteriorated following the death of his first wife – their mother, from whom he had been officially separated for 37 years – and his second marriage, a month later, to the mistress with whom he had lived since 1914. Asked in court, in 1960, how many children he had, he replied: “I don’t know – perhaps about half a dozen.”

Following his death, his widow said Pickard’s only ambition had been to live to the age of 100, but, she added – and not that anyone could have doubted it – “My husband lived the life he wanted.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe