It started with a bang and ended with a medical breakthrough in the shape of an artificial heart.

Scots intensive care unit director Professor John Fraser was working in his lab one afternoon when he heard thumping sounds from the room next door.

Checking it out, he saw a colleague, Dr Daniel Timms, trying to assemble what could loosely be described as a pump with leads and wires coming out of every corner.

“He said he was trying to create a mechanical heart, and from there, I was hooked,” said Professor Fraser, now based in Brisbane, Australia.

“The need for artificial hearts is desperate, with many patients dying waiting for transplant.

“So we assembled a specialist team and got on with making an artificial one.

“The route to the finished device involved Dan making trips to DIY stores for parts to create multiple prototypes.

“Dan and his late dad, who had heart failure, were driven and the journey to create the BiVACOR heart together was pure joy.”

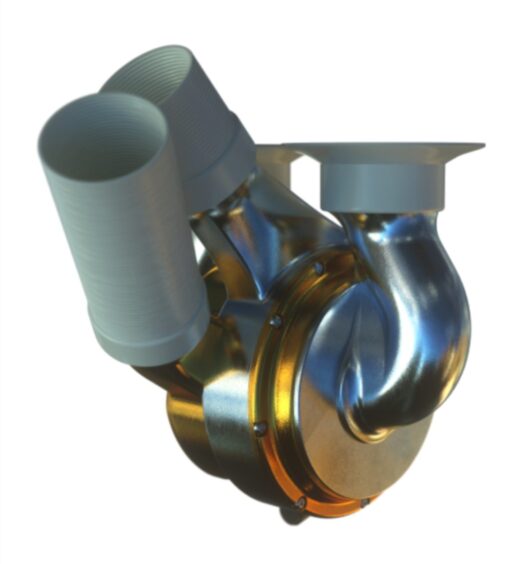

After years of prototypes, the BiVACOR totally artificial heart became the world’s first implantable rotary blood pump.

It was given to a patient in a Sydney hospital five months ago as a stopgap while a donated heart became available.

However, doctors believe its real future lies in replacing the human heart.

It weighs 1.5lbs and is small enough to fit a 12-year-old. It is powered by an external rechargeable battery that connects to the heart via a wire in the patient’s chest.

Blood is pumped around the body with a motor designed to avoid any mechanical wear to the parts. Magnets suspend the motor’s rotor, preventing parts rubbing and wearing over time.

The financial backers needed to get the device into production were found in the US.

“You have to cast a global net to get backing to drive development and production,” Professor Fraser added.

Successfully implanting the artificial heart was a steep learning curve.

The first patient at the Texas Heart Institute in July 2024 was never discharged from hospital. Other patients survived longer as transplant specialists overcame complications.

Sadly, early deaths in pioneering heart devices are inevitable.

The first heart valves implanted in Scottish patients in the 1960s had a mortality rate of 50%.

Today, survival is well over 90%.

Glasgow-born Professor Fraser, a father of five, was working on the project while also increasing the number of donor hearts.

He confesses to having a “disrupter” streak that drives him. The youngest of three from Glasgow’s east end, he insisted his brother, a GP who always wore ties and tweed jackets, was the “real doctor”, and his sister an artist, a true scholar.

He instead left Glasgow after two years as a junior hospital doctor to busk his way around the world in a kilt, stopping off in Mongolia to sing Burns and Celtic ballads.

Today, in his 50s, he is founder of the Critical Care Research Group, Australia’s largest multidisciplinary medical research group with a global presence.

His latest breakthrough is a device which keeps donor hearts preserved in their own mini circulatory system for long journeys before reaching patients.

“Once outside the body, hearts can rapidly deteriorate, making transplant extremely time-sensitive,” he said.

“Storing donor organs on ice slows down deterioration for about four to five hours.

“However, with the perfusion (circulatory) device, we can now keep donor hearts viable for more than 12 hours.”

His team achieved a new world record for distance and longest time a donor heart has remained outside a body before successful transplant into a recipient. This offers hope of international donations in the UK as at least 14 people die annually waiting for a heart transplant.

He is currently working on his newest invention, an inhaler of adrenaline which may one day provide provide life-saving treatment for people undergoing severe allergic reactions, or anaphylaxis.

“It was inspired by a colleague who survived cardiac arrest, but had severe brain injury, caused by delay of blood to the brain,” said Professor Fraser.

“If he had access to adrenaline faster, it may have been a different story.”

At least 30 people die in the UK every year from anaphylaxis, a reaction which causes the throat to close. The needle-free adrenaline inhaler is being designed so that it would quickly reach the blood flow through the lungs and one day could be administered in or out of hospital.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied