PRIVATISING the management of hundreds of job centres has cost taxpayers £11 billion more than ministers promised, we can reveal.

The Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) sold hundreds of offices to a private consortium in 1998 – then leased them back in a 20-year deal.

At the time it was claimed the PFI deal, one of the first of hundreds signed by the Labour Government, would cost £2bn and save the public purse £500 million but the contract ends today and the final bill has soared to £13bn.

The £2bn figure given out by the UK Government in 1998 covered the cost of providing the buildings but did include huge fees and service charges paid to the private consortium then known as Trillium.

A string of big changes to the contract, including billions of pounds worth of building alteration, sent the final bill soaring with critics arguing the taxpayer has been stung.

The true cost of the deal can be revealed as the DWP has come under sustained criticism for how cuts to Britain’s benefits bill have affected some of the country’s most vulnerable.

Medical assessments meant to strip claimants of disability benefits were branded inhumane while job centre closures meant people, including disabled claimants, were forced to travel miles to prove they were available for work and protect their benefits.

The DWP last year confirmed it would close 21 of its 119 offices in Scotland, including eight of Glasgow’s 16 job centres, resulting in longer journeys for claimants.

Yesterday, the SNP called for a Westminster probe into the deal while Charles Law, industrial officer with the PCS Union, said: “Our view was the estate was grossly undervalued when it was sold in 1998 and certainly now, with the rise in property prices, it has been an absolute gift to Trillium.

“In terms of the costs, that was always kept tightly under wraps but the impression on the ground was they were charging a lot for the most straightforward of tasks, like changing a light bulb.

“It was a rip off.”

Trillium, bought 700 DWP buildings at an upfront cost of £250m in 1998, even though the Government’s own advisers had valued them at between £316m and £361m.

The deal, according to the National Audit Office at the time, would save the taxpayer £500m over the next 20 years.

The DWP was then guaranteed the tenancy in as many of the buildings as it wanted to use in exchange for an annual payment to Trillium which covered rent, rates, cleaning, maintenance, catering and security.

In 2003, the PFI deal was expanded when the consortium, now known as Telereal Trillium, paid £140m for another 1100 offices, mainly job centres.

However, we can reveal, that between December 1998 and December last year, a total of £12.026bn was paid out for charges including rent, maintenance, cleaning and security.

Separately, a further £1.127bn was paid when the DWP asked for significant alterations to the offices it rented. And the taxpayer also got hit for £125m for when the DWP wanted to vacate offices ahead of the contracted date.

The DWP says the significant hike in what was eventually paid out reflects the big projects commissioned that were not envisaged at the start of the PFI deal in 1998, such as a programme of expansion of its offices and services in the wake of the 2009 financial crash.

Scores of PFI deals signed in the late nineties are due to come to an end in the coming years and it is feared similar hidden costs will emerge in other projects.

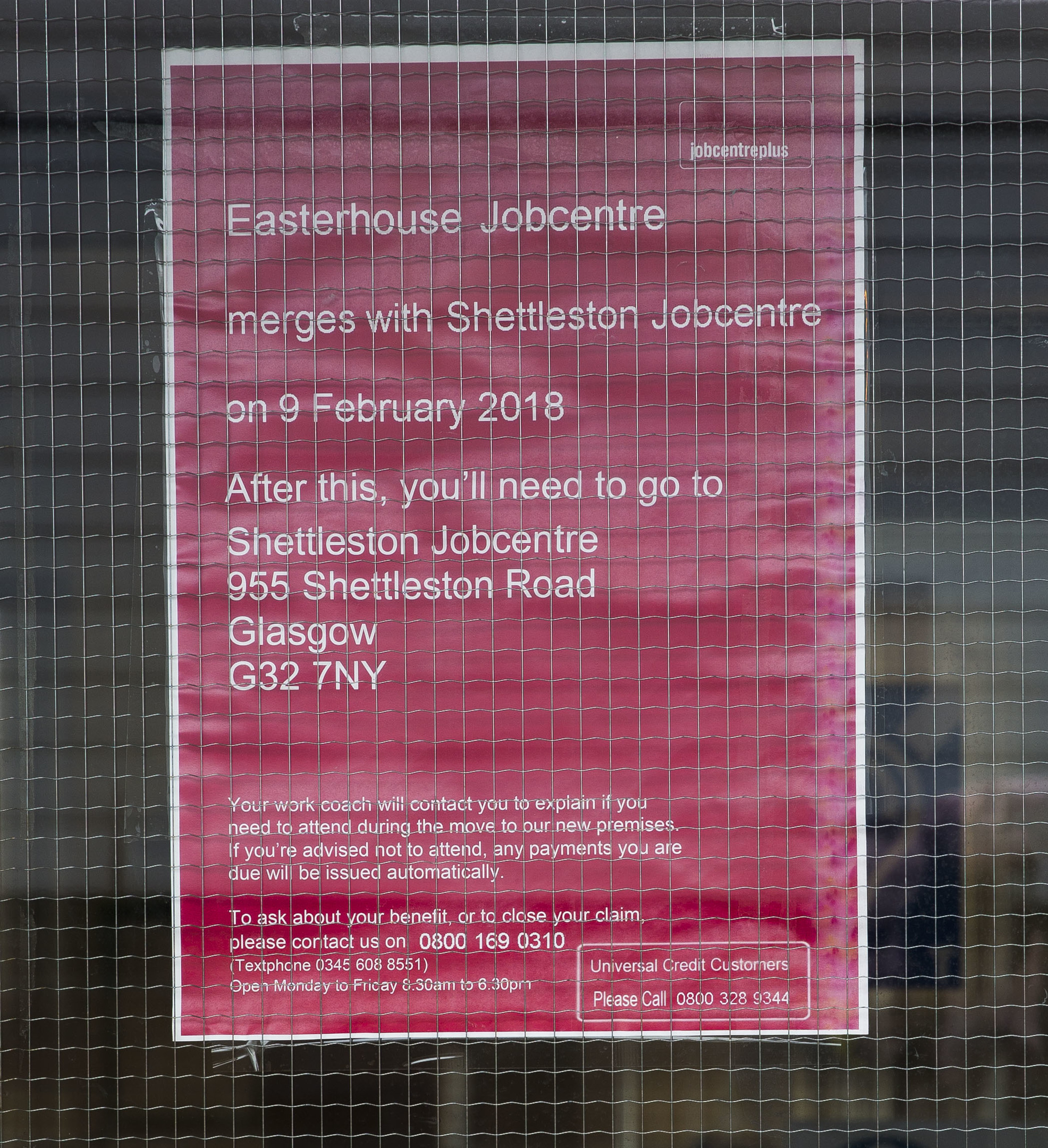

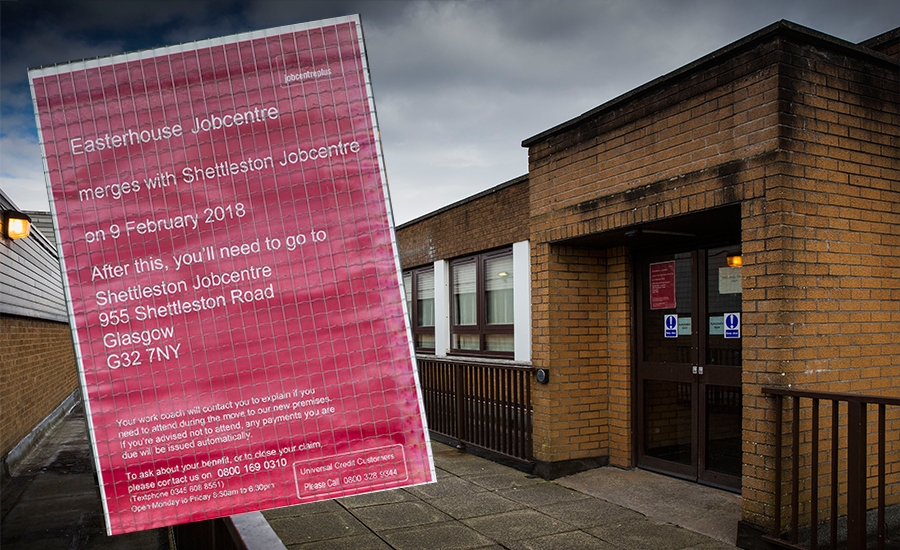

The job centre closure programme in Glasgow resulted in the Easterhouse branch closing in February. The closest centre is three miles away in Shettleston, which for people from Easterhouse attending compulsory appointments is two buses away at a cost of at least £4.50.

A DWP spokesman said: “We are now merging job centres across the country in a programme that will save taxpayers £135m a year for the next 10 years.”

A spokeswoman for Telereal Trillium said: “The National Audit Office has conducted two reviews of the contract during its lifetime, both of which were positive.”

£11bn? My son died because they stopped his £71 a week benefits

While the bill for managing job centres was soaring billions over estimates, thousands of people were losing their benefits as the DWP moved to cut costs.

David Barr knows the potentially unbearable cost of austerity cuts.

While the DWP’s privatisation of job centres was soaring £11 billion over budget, his mentally-ill son, also David, 28, was losing his benefits.

In 2013, his Employment and Support Allowance – £71.70 a week – was withdrawn after he was assessed fit to work.

Weeks later, he fell from the Forth Road Bridge.

His father David, 61, says his severe mental health problems were dismissed by the private firm hired to assess if claimants were fit to work.

He said: “My son wanted to work but he wasn’t ready, he needed support to get to that point, he needed medical help first.

“The decision was the final straw. It was all about money, they did not care about the consequences of their decisions.”

David, from Leven, said: “They are squeezing people on benefits but billions of pounds are quietly written off.

“You are never going to have a perfect system but look at the budget and tell me how much they are wasting that could support people back to work.”

The done deals that will cost us all a fortune

The rush to enlist private finance to fund public building projects will cost taxpayers, their children, and their children’s children billions.

Most basically, the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) works like a mortgage where public bodies get a new school, college or hospital up front for nothing then repay the costs to the private backers who built it over 25 or 30 years.

All risk is, supposedly, held by the private financiers but hundreds of projects were badly negotiated so this was not always the case and many consortiums have made a fortune from refinancing their loans but not sharing the spoils with the taxpayer.

Estimates suggest the total cost to taxpayers of Scotland’s privately built schools, roads and hospitals will hit £36 billion for projects that cost £8 billion to build.

The Tories started PFI but Labour championed the idea after coming into power in 1997. The SNP signed off on deals that will see the public pay £6 billion for projects that cost a third of that.

To make PFI the only game in town, the taps had to be turned off on traditional ways of funding schemes, such as public bonds or loans, and there was a big push on selling the fact it was “off the books”.

For example, instead of say £25 million appearing on a council’s balance sheet to build a new school, they only had £800,000 in that year’s repayments for the school.

One of the first deals was The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, which cost £184 million to build, but will see NHS Lothian pay back £1.6 billion in repayments and fees until 2034.

There are 350 privately-financed schools in Scotland and concerns have been raised about build quality and fire safety standards in many.

Overall repayments for PFI buildings in Scotland topped £1 billion last year but a new version of the funding model, which pays out less in profits to private finance firms, means there are decades of payments to private financiers left for the public purse north of the Border.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe