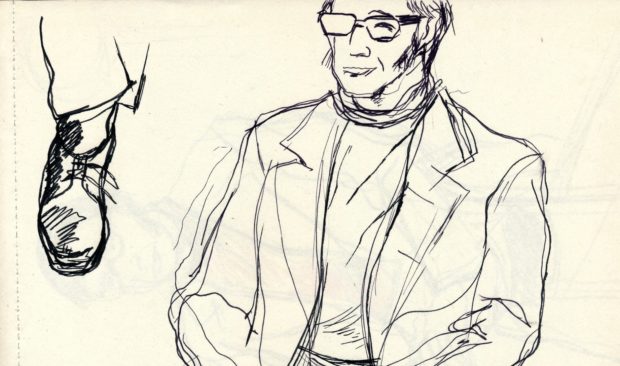

They had lain in a drawer for decades, sketches of the poet as a young man, the first lines drawn in the creation of one of the most famous pieces of modern Scottish art.

When artist Sandy Moffat discovered some old notepads while clearing out a drawer, he’d no idea how significant the sketches inside would prove to be.

Now, to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of Edwin Morgan, the country’s first National Poet, Moffat is sharing the remarkable rediscovered working sketches made as part of a historic commission for the then Scottish Arts Council in the late-1970s.

And, 40 years after their creation, the early pieces have inspired the man who made them to revisit them for a present-day reinterpretation.

The outlines from Morgan’s series of sittings with Moffat, seen for the first time in today’s Sunday Post, come to light with the launch of a programme by the Edwin Morgan Trust marking what would have been the Makar’s 100th birthday tomorrow.

The works afforded Moffat, one of the country’s most revered painters, who taught at Glasgow School of Art, a nostalgic reverie back to the works he composed in the late-1970s and early-1980s.

He said: “Old sketchbooks pile up and you forget about them, then 20 years later you don’t have a clue what’s in them so you rake around and you find these things. It gives you quite a shock, but it’s good to have them.

“I must have used several different sketchbooks. There’s one I found that had drawings of Iain Crighton Smith, Hugh MacDiarmid and very detailed studies of Robert Garrioch. Edwin was in that too.”

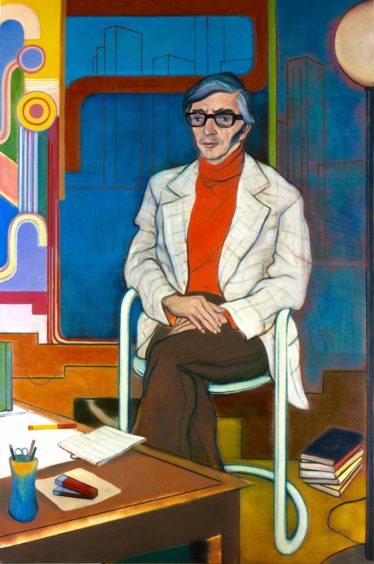

Moffat’s portrait of Morgan hangs in the National Galleries of Scotland, alongside Poets Pub, his famous imagined coming together of modern literary titans.

The work was part of a commission which saw the artist paint eminent Scottish writers and came from a series of meetings between the men at Glasgow University, where Morgan taught, his flat on Great Western Road, and Moffat’s studio at Glasgow School of Art in the late-1970s.

Of his find, Moffat said: “Drawings like these are like notes. You start off looking around, seeing things on his desk, pens, paper, making a rough note of the things that are there.

“In the final painting, you can see the outline of the Hunterian Gallery at Glasgow University, there’s a nod to Paolozzi, a Bauhaus chair and things that add up to Morgan’s interest in contemporary forms of poetry and art, things I could use to say this is his view of Scotland.

“And he was a great translator. He translated Russian, Hungiarian, German and so on.

“We had access to a fantastic world view from these guys, so you could only ever benefit from sitting listening to him.

“He also experimented with different forms of poetry, like concrete poetry, visual arrangements of words and sentences, and it was good to talk to him about things like that, He was a great fan of the painter Joan Eardley, and that dialogue between the arts has always interested me – poets, painters, film makers, theatre people, musicians, how we can share things and work together.

“I wanted to paint modern Scotland, as it were, or a vision of Scotland that was an important place going somewhere, that had an important history. That’s what the poets talked about in their work, as well.”

Moffat recalled how Morgan was “the perfect subject”.

He said: “He didn’t fidget or muck about. Some people fuss about, they look in the mirror. He was just fine. He wore a very nice jacket, light and colourful, and I told him to keep wearing that, that it was the jacket I wanted to paint him in. That was a way in for me, because you’re always looking for a hook. It got me off to a good start.

“Obviously one of the treats meeting the poets was listening to what they had to say about things. I used to take longer on the drawings so I could have another session just so I could listen to what they had to talk about. There was no point in rushing.”

It was while studying Edinburgh College of Art that Moffat first encountered Morgan, who died aged 90, 10 years ago in Glasgow, at a poetry reading in the capital in the 1960s with Hugh MacDiarmid and Norman MacCaig.

The artist recalled: “It was pretty euphoric. One of the poems he read then was The Death Of Marilyn Monroe. That was a real eye opener – a guy in Scotland writing about Marilyn Monroe in such a different way. It seemed to me then that we in Scotland could do these things. That felt important. Those readings really seeped in to what I was working on and thinking about.”

One other sketch from the sittings came to light 15 years ago when a former colleague of Moffat’s came across it while clearing out a drawer. It now resides at Glasgow University’s Scottish Literature Department.

While Moffat has no plans to exhibit the discovery of forgotten artistic treasures, their discovery – and the Covid-19 lockdown restrictions – have given the artist the impetus to revisit his old subjects.

“We have time on our hands, so I’m maybe going to poke my nose into some of these old sketchbooks because I had a lot of sketches that didn’t go into the big painting,” he said.

“So I’ve been thinking about using the time to go back and see if I can make something of the initial idea, do it a completely different way. There’s more to be said, so why not have a go.”

And, having spent time capturing Morgan’s essence in what has come to represent both men’s legacy, the painter is well-placed to consider what the poet might think of Scotland today.

He said: “I think Edwin’s position now would be much the same as it was when he died. What was it he said in poem he wrote for the opening of the Scottish Parliament? That we’d made a start but that we needed to be more courageous, more ambitious, not be cautious.”

Moffat last met the Makar shortly before his death.

“He’d gown a muckle big beard and we had a laugh about it,” he said. “I said I should come back and do a new painting. But he was 90-odd and, though it would have been good to go back, he was very frail, and it might have been an imposition.

“It meant a great deal that I was able to paint the poets in the first place. Some of them weren’t that well known at the time, a lot of people had no idea what they looked like, so I feel like I contributed in some small way towards them becoming household names.

“Sometimes artists throw things out and they don’t know what they’ve thrown out. I’ve made some mistakes with that in the past. But I’m glad I held onto this one way or another, even at the bottom of the pile.”

Go to edwinmorgantrust.com for more information on the programme celebrating 100 years of Edwin Morgan

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA

© PA