THERE’S a scrap of paper in my drawer at work that has “petit pois” scrawled across it in capital letters. It’s nothing, just a scribbled reminder, a shopping list. It is precious beyond words.

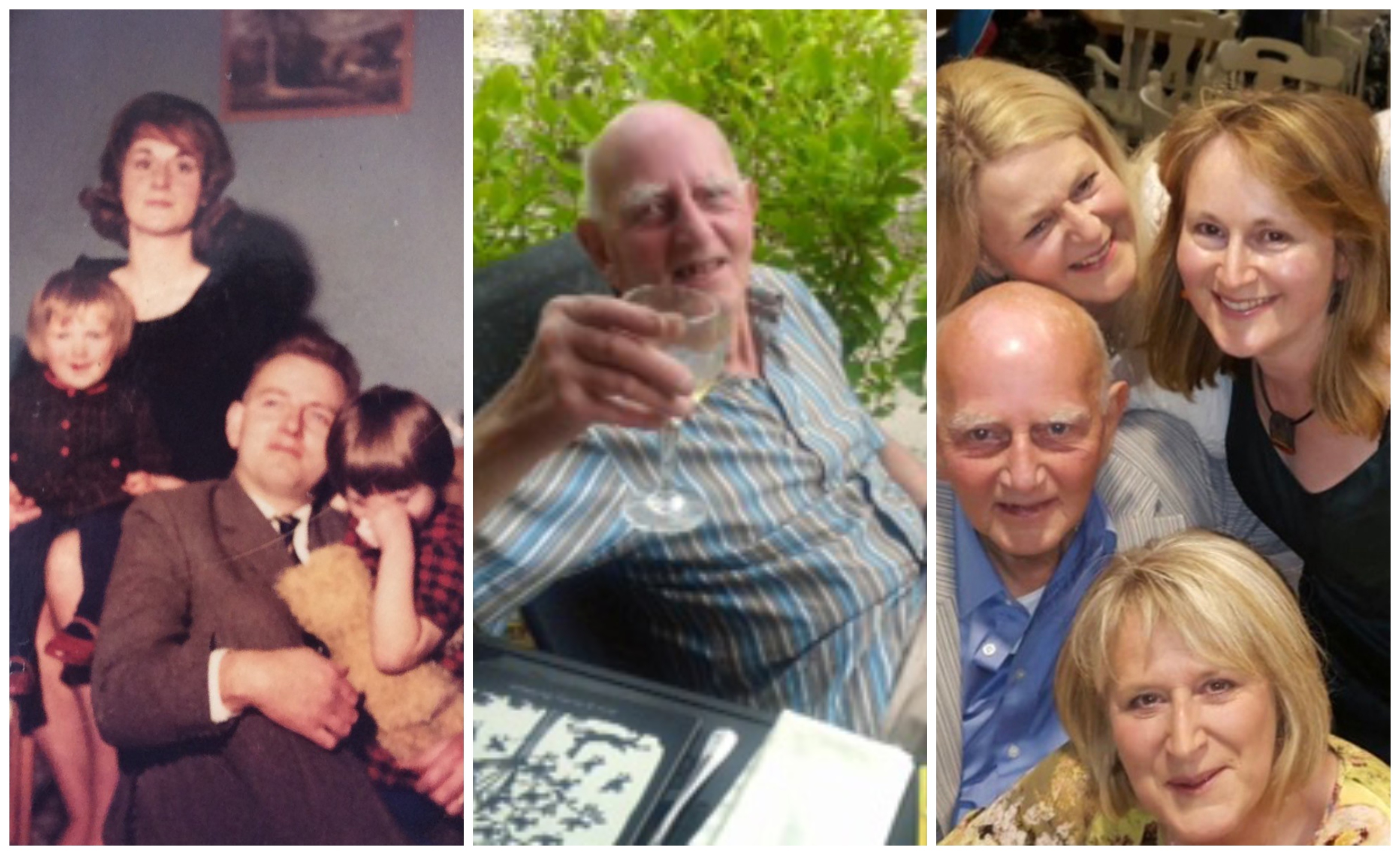

My dad gave it me before he died exactly a year ago and that “petit pois” is so him. Asking for peas would have seemed too mundane, too pedestrian for a man with a palette of such self-proclaimed sophistication. Yet give him a plate of mushy peas or a slice of Spam and he would have been delighted. He was a man of contradictions. A contrarian and an eccentric. We miss him terribly.

We’ve reached that time, the first anniversary, when we’re not able to think about dad as being alive “this time last year” and it’s like a second grieving.

It’s not that the sadness has ever gone away. There have been surprisingly deeper depths to plunge with every month that passes and there’s a gnawing gloom hovering over everything, all the time.

It’s strange because I didn’t think about my father every day when he was alive, but in death, he’s in my thoughts constantly as I cling to every bit of the past – a time with him in it.

It’s not that there are regrets. There’s nothing particular that I would do differently given the chance. It’s just the loss is so damnably final and there’s no new memories to forge or to plunder.

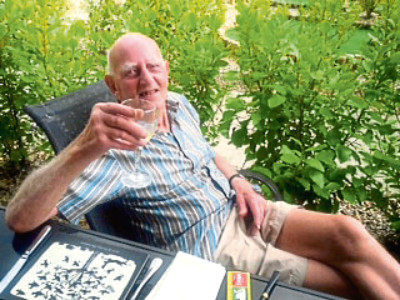

And this time of the year is just so dad. The sun comes out and we smile, thinking of dad in the tiny shorts that he wore from April onward. The cricket, Wimbledon and the World Cup, all signposts of his summers. Of him drinking cider in front of the TV with the curtains drawn but billowing in the gentle, warm breeze of a Blairgowrie summer afternoon.

We all gathered at mum and dad’s, Sheila and David’s, last month to mark his first birthday without him there. He turned 84 last year and was gone a month later.

June was the first Father’s Day when I didn’t buy a card. And this weekend will be the first time to acknowledge we have got through a whole year without him. There seems to be a lot of firsts in this process of grieving. First, foremost and most fundamentally, is the fact that he’s gone.

None of us expected the hole to be this big. And frankly, it’s been a shock. My dad was not a showy man, not a man to make grand gestures or wear his love for his three daughters on his sleeve, but we just knew.

I know that for many there must be an expectation that a year marks a time to move on but I am learning that grief does not have an expiry date.

The acute pain has worn off, the tears have lessened, but I still wake up each day with a hollowness in my heart, a heaviness in things I do. I have accepted the loss, of course I have, and like my mum and my sisters, I am redefining my life and who I am. I have become the daughter that no longer has a dad. My mum doesn’t have her husband. We have accepted that but what is harder to let go of is the ache of just wanting him back, of wishing my mum wasn’t on her own or that when I drive up to the house he’d be there, puffing on his pipe, balancing a glass of wine and impatiently tapping his watch to signal the fact that he wanted to eat now.

Dad lived in a household of four women. A heady mix of raging hormones and all the associated door banging, screaming and tears that entailed. He was a calm centre, a source of both serenity and mischief. He’d sit stuffing tobacco into his pipe while all hell let loose and then walk out of the room in a cloud of pipe smoke, often lobbing in some provocative comment that would get us all started again and disappear off to his beloved garden, usually with a glass of wine, and hunker down, waiting for the storm to pass.

Nothing seemed to faze dad about living with a bunch of divas. I think it amused him. I remember a particularly fraught shopping expedition in Perth to get a new coat for me when I was about eight or nine. Mum was at the end of her tether because the only coat I wanted was an expensive, purple, vinyl, trench coat. Big lapels. Totally impractical apart from the obvious of being wipe-clean. Mum dragged me off, crying, to tell dad who was lying in the sun on the North Inch and he said that if that was the only coat I smiled in then just to buy it.

Maybe it was about him always opting for an easy life, but I can’t remember him ever shouting at me and I also think he rather relished the madness of living with these bonkers girls simply because we were his bonkers girls.

Not that dad wasn’t a little bonkers himself. He could walk past us in the street and not recognise us. He would wake us with tuneless yodelling from the bathroom where he would insist on taking freezing-cold showers and it was also from the bathroom that strange snapping noise would come that would have our imaginations whirring about what men actually did in there until we discovered he was laying out a hand of bridge on the bathroom floor.

Dad’s mind might have butterflied from here to there, always in motion – cricket, bridge, wine, garden, projects – but his one, constant preoccupation was my mum. He simply adored her.

Mum says dad always made her feel safe and while that is undoubtedly true, and it is also that ‘being safe’ that gave us the inner confidence to become the independent women we are, it is also a paradox because dad was also the most unsafe man I know.

He would be the one to throw petrol on fires, to have wiring held together with Band Aids, to have ladders with broken treads, to not notice danger ahead – he once threw me from height on to the ground as a baby because he was watching football and as a goal was scored he threw his hands in the air and just forgot what he had been holding.

He always had cuts and grazes from some accident in the garden and it was no coincidence that mum banned him from ever having a chain saw.

I tearfully asked dad around this time last year when it was becoming clear there was something very wrong, whether he wished he’d ever had a son. He looked at me incredulously with those blue eyes of his and asked why he would ever have wanted that when he had us girls. A few weeks later he was gone and, for the first time in our lives, his girls did not have him.

And that’s the nub: I’ll never have someone look at me like that again. I am no longer that daughter. It isn’t just that my dad has died, it’s that he took a part of all of us with him.

Death changes life for us all.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe