IT has taken a lifetime of working with words, 10 books, a best-selling memoir and her debut novel, but Sally Magnusson is now willing to accept what her readers have known for many years.

She’s a writer.

One of Scotland’s best-known broadcasters after years presenting Reporting Scotland and Songs of Praise, Sally has just published her first work of fiction, The Sealwoman’s Gift.

And with it, she experienced a professional epiphany at the age of 62. Sally said: “I still can’t take myself quite seriously when described as a novelist.

“But someone asked the other day how they should describe me, and it occurred to me that for years I’ve been described as ‘broadcaster and writer Sally Magnusson’.

“I thought maybe it should be ‘writer and broadcaster’ now. That feels good to me.”

But the mum of five has no inclination to hang up her microphone.

“Not to say anything disparaging about the other part of my work,” she said. “It’s just that the writing has come to mean more and more to me over the years.”

Her new novel came about in the wake of her best-selling memoir Where Memories Go, a candid account of how a family dealt with the gradual disappearance of a loved one descending through the stages of dementia.

It told the poignant story of how Sally and her family learned to cope as her mother Mamie – a former Sunday Post journalist – lived her final years with Alzheimer’s.

The book remained on the best-sellers’ list for months and was praised by people in the caring professions as much as literary critics.

Yet as well as marking her out as a spokesperson on dementia – and leading to the formation of the charity Playlist For Life – its success posed Sally a happy problem.

She said: “My publisher was anxious that I write something else after Where Memories Go did so well.

“We talked about the things that interested me, and I considered writing another non-fiction book about music and dementia.

“But in the end I felt I needed to go somewhere else completely.”

That turned out to be an island off the coast of Iceland in the 1600s.

The Sealwoman’s Gift takes as its starting point one of the most terrifying chapters in Icelandic history, when hundreds of islanders were abducted into slavery by pirates from Morocco. Inspired by the country’s literary sagas, the novel’s heart-wrenching fiction is built around the bloodied bones of fact, words hauled from written records of the 17th Century.

Sally said: “I came across an English translation of Olafur Egilsson’s memoir, and that really opened my eyes to an extraordinary story: this priest who was abducted with his family, taken to Algiers and then has to leave them behind to make his way back to Europe to raise a ransom for them.”

Much of the story centres around Asta, Olafur’s wife.

Sally said: “So little was known about the life of women either in Europe or in Algiers.

“I wondered what their experience was like and how to make that engaging to a modern audience – writing about the reality of that experience in the 17th Century in a way that speaks to the universal experiences of grief, loss, love and so on.”

Years of writing for newspapers didn’t come close to preparing the experienced journalist for the harsh realities of draft-writing works of fiction.

She said: “I don’t think I realised how much I’d bitten off until I started. I was at a dinner with writers James Robertson (author of And The Land Lay Still) and Sarah Perry (The Essex Serpent), talking to them about my first draft, and how I realised I was going to have to start again because it wasn’t really working.

“I was despairing because I’d done 100,000 words which had taken me months. They laughed and told me to come back to them when I was on the fifth draft.

“In journalism, you’re used to doing things quickly, to a deadline, as well as you can. I had to get used to the whole mindset of honing and refining and editing and junking and starting again.

“But, believe it or not, I’ve already started another one.”

And she remains confident that physical books are here to stay, despite the rise of eBook readers.

She said: “I’m tremendously evangelical about books. There’s nothing like reading the word on the page, and I think the Kindle moment has passed its peak, and there’s a movement back to book in paper form.”

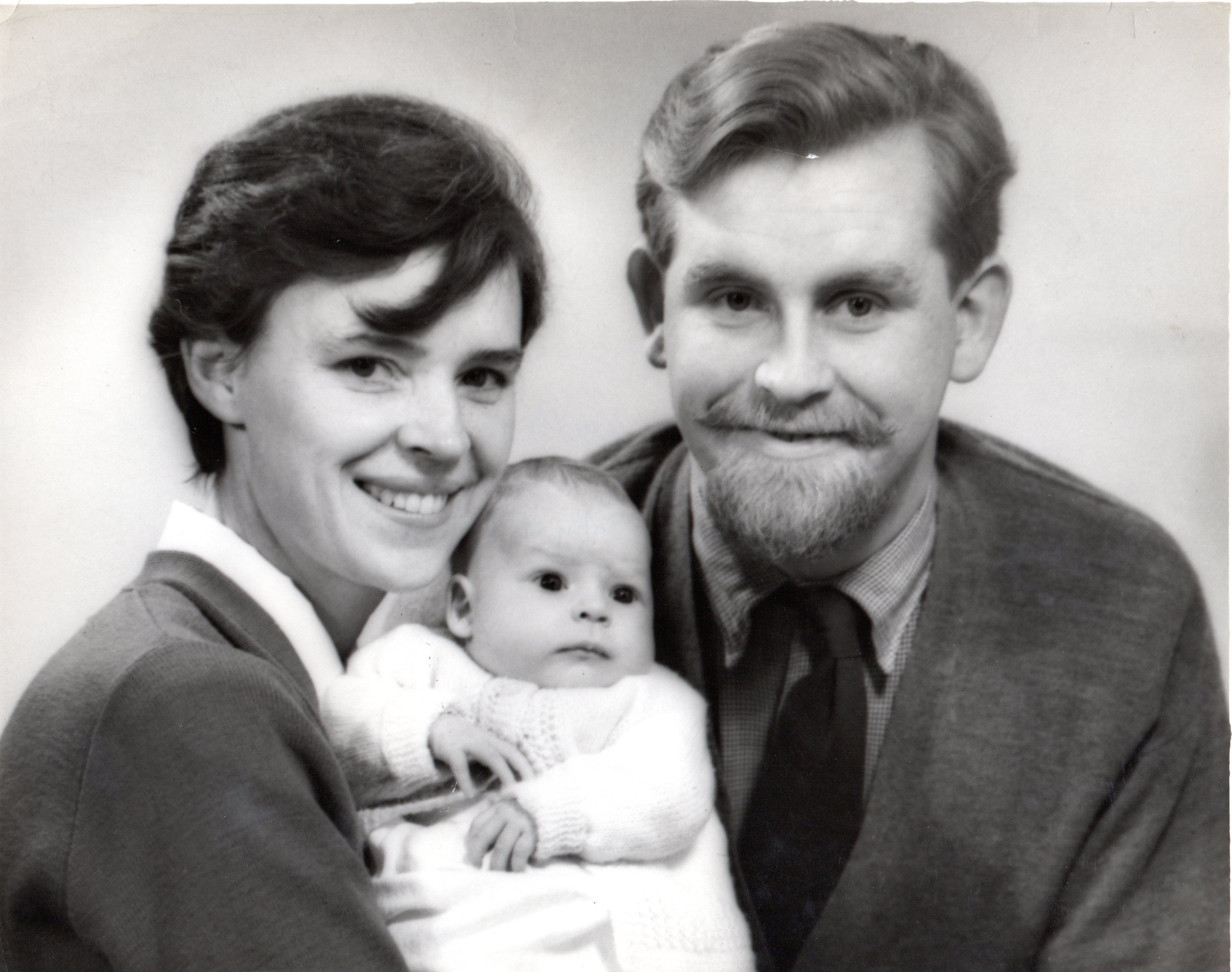

Sally recalls how she read the works of Enid Blyton “by the bucketload” as a girl, and how reading was encouraged, but never prescribed, by her mother, Mamie, and father, the late journalist and broadcaster Magnus Magnusson.

“Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings was a seminal book for me when I was about 12,” she said.

“I adored that sense of ‘northerness’, Tolkien playing with the sagas and Norse myths.

“I was reading for myself, and going to Iceland with my father at that age, seeing where the sagas had happened, in this crucible of storytelling that Iceland is.”

The fact that neither parent is around to see her break new ground in her career is one note of regret for Sally, who is married to film-maker Norman Stone.

Magnus died in 2007 and Mamie in 2012.

Sally said: “I often think it’s a pity they aren’t here to share things with, that I can’t sit down over a cup of tea and tell my mum I’m stuck, and have her tell me to just plunge in and fix it later; or that I should write an Icelandic novel about sagas and folklore and I can’t talk to my dad about it, can’t show it to him, even if he might tell me it’s a lot of rubbish and to try something else next time.

“I miss that. I would like to think that anything I do would please them.”

Sally appears at Glasgow book festival Aye Write, Royal Concert Hall, March 18, at 4.45pm

Our work will only be done when everyone knows music is key to unlocking anguish of dementia

Sally had no notion of starting a charity about music’s therapeutic impact on people with dementia when she started writing a book about her mother’s experience with Alzheimer’s disease.

Even now, as Chair of Playlist For Life, she hopes to see the day when the charity can be wound down.

The organisation’s aim is to make the association between music and dementia as intrinsic as that of the graze and the sticking plaster.

“Once everyone knows that, we’ll be able to say our work is done,” said Sally, who set up the charity in 2013.

“We want to get to the point where anybody who is diagnosed with dementia, or hears the word, will simply know that making their own playlist is the thing to do next. There are still lots of people who don’t know this. We’re still scratching the surface.”

Playlist For Life’s impact has seen their work endorsed by the Care Inspectorate, and is changing the approach in some care homes.

A free digital app was launched last year, to help families compile playlists, with the help of a virtual “music detective”.

Sally said: “If you’re able to make someone less agitated, more engaged and more lucid just by thoughtfully introducing music to them, especially at the times they find most difficult, that’s transformational and is already informing the culture in care homes.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe