It was a truly hellish journey but did not end when Dante Alighieri finally set down his quill after writing his epic trilogy The Divine Comedy.

From the Renaissance to TS Eliot and even, more recently, The Sopranos, the three books, and their playful and brutal depictions of the afterlife, have been carried like a flame by artists and writers since it was published 700 years ago.

And that includes being shuffled up and down Byres Road in Glasgow’s West End in a Tipp-Ex-marked shoulder bag.

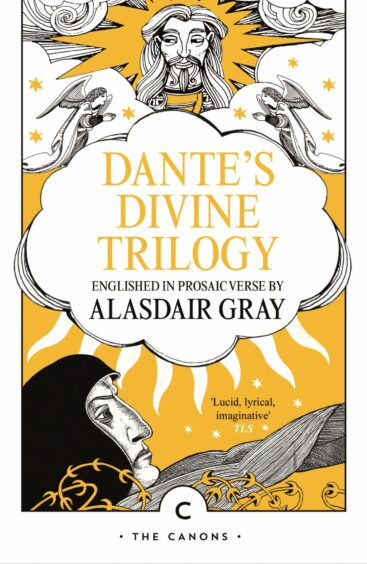

The late artist, writer and polymath Alasdair Gray’s final work was to reinterpret Dante’s Divine Trilogy; now Hell, Purgatory and Paradise have been collected together ahead of a celebration of his life, which is being called Gray Day, on February 25.

For Gray, who died in 2019 aged 85, the work wasn’t simply a final confrontation with his own impending mortality. It also spoke to his desire to share his philosophy of literary and personal collaboration according to his friend, and curator of the Alasdair Gray Archive, Sorcha Dallas.

She was tasked with the difficult task of sorting through his tenement flat following his death. It was while poring over his sketches, writing and books she discovered Dante’s journey was a lifelong fascination for the writer of seminal Scottish literary classic Lanark.

“Going to Dante, thinking about it and translating it, was something he’d been referencing for a long time,” says Dallas. “I found annotations in books he’d made where he was obviously thinking about tackling this kind of work.

“This project talks about major things: heaven, hell, life, death and everything in between.

“Other writers and artists have tackled it too, and I think he was very aware of trying to add to that discussion and dialogue.”

Gray’s passion for marginalia (notes written in the margins of books) might infuriate a bibliophile, but it was part of his creative process.

“He was having a conversation, not just with authors of old texts but even with earlier entries he made as a younger man,” Dallas explains. “The books were a dialogue, and not just with the author but with himself.”

In The Divine Comedy, author Dante, who is also the book’s hero, meets classical poet Virgil, who guides him on his journey to reach heaven. The work was pivotal to literature because it blended reality, religions and myths with the confidence a modern-day Marvel movie might team Norse God Thor with Nazi-punching Captain America.

“It’s not strictly a translation because he didn’t speak Italian,” adds Dallas. “He took six or seven English versions of Dante’s Inferno and created his own interpretation.

“What he did was try to infuse the essence of what Dante was saying and then sort of shape it into his own thoughts and words.

“For him it was about distilling the words into their purest form so the most people can access and understand them.”

Dallas remembers as a student seeing Gray walking through Glasgow’s West End, sporting his trademark bag with “Please return to Alasdair Gray” alongside his address Tipp-Exed on the side of his satchel. She wrote to him and he suggested they work together.

“He wouldn’t consider himself a mentor because that would suggest a hierarchy and he treated people as equal,” says Dallas. “He loved meeting people so whether it was a book signing or you bumped into him in the pub you could have a great conversation that was really memorable.

“There’s an opportunity on Gray Day for people to share their own personal connections or tales around Alastair, whether they’ve met him or not; maybe they had read Lanark and it meant a lot to them or they got married under the auditorium of Oran Mor.”

Among the contributors to Gray Day, taking place in Oran Mor in Glasgow, will be crime writer Val McDermid and playwright Liz Lochhead, as well as poet Hollie McNish.

Much of his work now resides at the Archive, located at The Whisky Bond in Glasgow.

In 2014 Gray experienced a fall which took him to the intensive care ward and left him in a wheelchair.

Dallas recalls how that curtailed his painting and illustrations but also left him focused on his final work of interpreting Dante Alighieri.

“Like everything with Alasdair, even though it was his final work, I found the copy of Hell after it was printed,” she says. “He was still going over it with a pen and Tipp-Ex, editing and improving it.

“Other writers have adapted Dante and altered it so it’s relevant to their own biography,” she says. “It just shows that a text 700 years old can still be relevant all these years later, after all these different interpretations, which is fascinating.

“As a writer and an artist Alasdair created that space for others with a huge body of work which ranges across the personal and political. He left a huge amount for us all, and that’s the reason for the archive to exist, and for Gray Day. They are so people can share their own story and to interpret and shape his legacy.

“His legacy doesn’t really end with Dante, it will change shape as we continue to work, grow and collaborate with others.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock