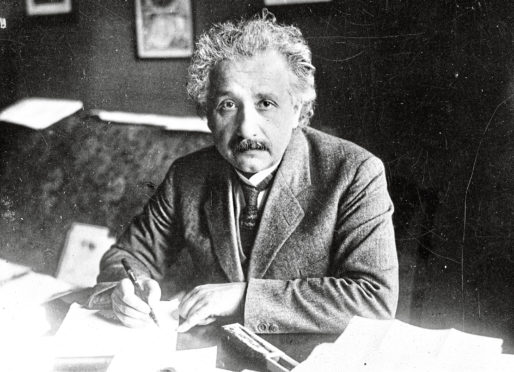

Britain helped German-born Albert Einstein to become the father of modern physics, as the country gave the Jewish scientist refuge from the Nazis in the lead-up to the Second World War.

Here, author Andrew Robinson tells Sally McDonald the Honest Truth about Einstein on the run.

Why did you write this book?

For the 2005 centenary of the discovery of Einstein’s theory of special relativity, I published a book on his life and work but it didn’t do full justice to his relationship with Britain.

It is the country that made him into a physicist, and later, an international star by proving general relativity experimentally in a 1919 solar eclipse.

The UK also gave him refuge from the Nazis in 1933. In 1955, just before his death, along with Bertrand Russell, Einstein signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto against the spread of nuclear weapons – his most enduring political statement. As Einstein said: “My work has received greater recognition in Britain than anywhere else in the world.”

To where did your research take you?

The Einstein archives at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and the untapped archives of Oxford University, where Einstein was a guest in 1931-33. I also dug into the archives of British newspapers, who covered Einstein extensively from the ’20s.

And I visited Einstein’s rural 1933 hideaway in Norfolk.

The most surprising discovery?

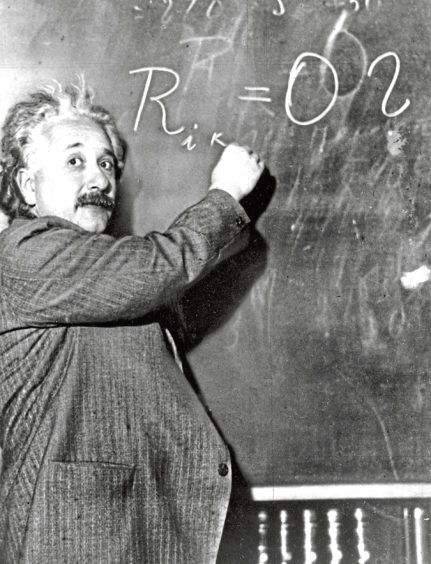

Einstein’s Oxford blackboard, preserved in 1931 and today the most popular object in Oxford’s History of Science Museum, contains a mathematical error! But this fits with his modest refusal to publish his 1931 Oxford lectures because he knew they would soon be outdated by his and others’ work.

And your most shocking?

That Einstein’s host – who gave him refuge from the Nazis – MP Oliver Locker-Lampson had published a highly laudatory and partly bogus newspaper article about Adolf Hitler in 1930.

Why is Einstein so important to the world of science and why is he a household name?

Over the last century, general relativity has become the most widely accepted explanation of the structure of the universe.

In addition, Einstein launched quantum physics, even though he could never accept the quantum mechanical idea that physical reality seems to be probabilistic. “God does not play dice” with the universe, he wrote in 1926.

Why was Britain so important to him?

Einstein was born in 1879 in Germany. He grew up there and in Italy before becoming a student in Switzerland. But he was hooked on British physics, particularly the work of Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday and Scotland’s James Clerk Maxwell.

He wrote that Maxwell’s field theory “is the most profound and fruitful one that has come to physics since Newton”. In addition, Einstein’s host in Britain in 1921, Lord Richard Haldane, was born and educated in Edinburgh; and perhaps his closest friend among physicists, Max Born, settled in Edinburgh in 1936 as a refugee from Germany. In 1933, Einstein gave a lecture at the University of Glasgow on general relativity, and received an honorary doctorate.

Why did he leave the UK and where did he go to?

He left Britain in 1933 for America, where he settled at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton.

Einstein wanted to be in a place where he was free to think about theoretical physics, entirely according to his own wishes. The Institute offered this, without any lecturing or social obligations.

What would you like people to take from this book?

Most writing on Einstein tends to focus on his science or his other activities, and does not unite the two. His relationship with Britain, by contrast, gives us access to the whole man, with all of his strengths and weaknesses.

And it reveals his unique sense of humour. A favourite Einstein quip is: “To punish me for my contempt of authority, fate has made me an authority myself.”

Einstein On The Run: How Britain Saved The World’s Greatest Scientist, by Andrew Robinson, published by Yale University Press

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© AP

© AP