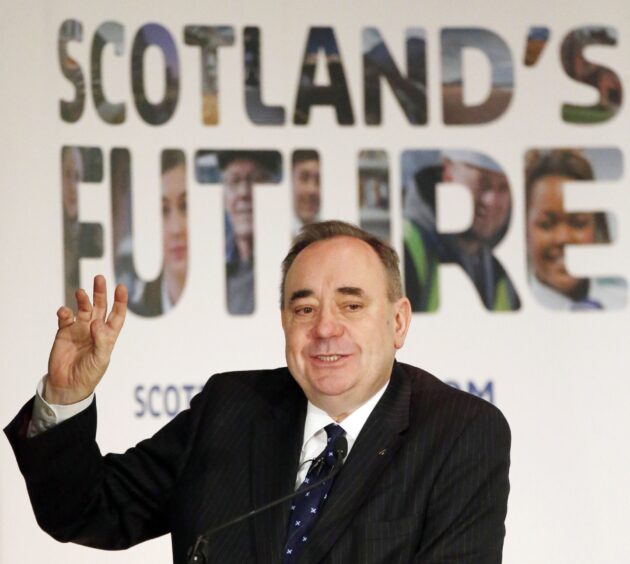

Former first minister Alex Salmond, who died yesterday at the age of 69, will be remembered as one of the most significant politicians of his generation, taking the Scottish National Party from the political fringes to government and the nation to the brink of Scottish independence.

Loved and loathed in equal measure, Salmond led the country between 2007 and 2014, and also pushed support for Scottish independence to record levels during the 2014 referendum campaign.

Born in Linlithgow in 1954, Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond became active in the SNP while at St Andrews University in the 1970s, before working as an economist, including at the Royal Bank of Scotland.

As a young and brash newcomer, Salmond played a role in the breakaway faction of the SNP known as the “79 Group” which sought to take a more left-wing stance.

His brief expulsion as a result did not hinder his advancement within the party in the long term, with his election to leader coming in 1990.

Salmond was elected to Westminster in June 1987, winning the seat of Banff and Buchan.

He characterised his early time at Westminster as “a one-man campaign of parliamentary disruption”, and made headlines when he disrupted Conservative chancellor Nigel Lawson’s budget speech in the House of Commons.

The incident resulted in him being suspended for a week.

In 1997, after the election of a Labour government at Westminster, a referendum to establish the new Scottish Parliament was held.

Two years later, as well as being the MP for Banff and Buchan, Salmond was elected MSP for the same constituency in the first elections to the Scottish Parliament. But in July 2000, Salmond announced his decision to stand down as SNP leader to concentrate on Westminster.

He was succeeded by John Swinney.

In 2004, after Swinney resigned as leader, Salmond said he had no intention of returning.

But he later announced he would stand for the leadership, and in 2007 returned to Holyrood, winning the Gordon constituency.

The SNP became the largest party with Salmond elected Scotland’s first SNP first minister.

Four years later, he led the SNP to a landslide victory in the Scottish Parliament election.

Popular policies such as free university tuition, free prescriptions, a freeze on council tax, and Salmond’s seemingly innate talent for outmanoeuvring his political opponents helped to assure electoral success.

The majority win was even more impressive considering the voting system at Holyrood is essentially designed to prevent such a result.

The landslide also gave Salmond the chance he had waited all his life for – an independence vote.

Salmond signed the Edinburgh Agreement with David Cameron on October 15 2012, setting out the terms of the referendum to be held in 2014.

Voters were asked: “Should Scotland be an independent country?”, and as the September 18 vote drew closer, the polls narrowed, and Yes Scotland appeared to have the momentum.

But the result – a 55% to 45% vote to stay in the UK – led to his resignation on September 19.

Announcing his plans at Bute House, he said: “I am immensely proud of the campaign which Yes Scotland fought and of the 1.6 million voters who rallied to that cause by backing an independent Scotland.

“I am also proud of the 85% turnout in the referendum and the remarkable response of all of the people of Scotland who participated in this great constitutional debate and the manner in which they conducted themselves.”

Salmond was succeeded in both posts by his deputy Nicola Sturgeon in November, but those who thought he would step back from frontline politics were mistaken.

The following year, Salmond returned to Westminster as MP for Gordon. As the party’s foreign affairs spokesman, and with a UK-wide profile thanks to the independence referendum, Salmond became one of Westminster’s biggest names.

But in June 2017, in a snap general election, Salmond lost his seat.

He went on to stage a chat show during the Fringe, then hosted a TV show on Russian broadcaster RT.

Salmond resigned from the SNP in 2018 in the wake of sexual harassment allegations. He went on to launch a court action against the Scottish Government to contest the complaints process that was activated against him.

He admitted he was “no saint” but repeatedly denied “any semblance of criminality”.

Salmond formed the pro-independence Alba Party in 2021 but the party failed to win any seats at Westminster or Scottish Parliament elections.

The most controversial moments in Salmond’s career included his handling of planning for Donald Trump’s Scottish golf course and Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill’s decision to free Lockerbie bomber Abdelbaset al-Megrahi on compassionate grounds.

Salmond’s missteps also included offering RBS boss Fred Goodwin his backing in the disastrous takeover of the ABN Amro bank, and describing UK involvement in the Nato bombing of Serbia in 1999 as an “unpardonable folly”.

Just last month, Salmond said he regretted his decision to step down the day after the referendum vote, describing it as a “mistake”.

He said he would not have handed the reins to Nicola Sturgeon at the time had he known how the next 10 years would play out.

Salmond recently hinted that he would retire from frontline politics if Alba failed to make Holyrood breakthrough in 2026.

But he never gave up on his lifelong dream of Scottish self-rule, even just before his death tweeting about independence.

It is designed to diminish the status of our Parliament and the First Minister. Part of becoming independent is about thinking independently, not subserviently. John should have politely declined the meeting with the words “Scotland is a country not a county”. (5/5)

— Alex Salmond (@AlexSalmond) October 12, 2024

A life in politics that latterly was never short on scandal

Although considered one of Scotland’s most influential and successful politicians, Alex Salmond’s decades-long career wasn’t without controversy, and his legacy was most notably damaged when he faced charges of sexual assault and attempted rape in 2019.

A long, drawn-out political scandal involving Salmond, and the wider Scottish National Party, was first sparked in 2018, when the Scottish Government received formal complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct, allegedly committed while he was first minister.

Under new rules introduced following the #MeToo movement, senior Scottish Government officials conducted an internal investigation into the historic allegations made by two female civil servants, and its findings were passed to Police Scotland, which subsequently launched its own criminal investigation.

Salmond vehemently denied the allegations, but ultimately resigned from the SNP after 45 years – and immediately launched his own legal challenge, accusing the Scottish Government of abuse of process. In January 2019, the court of session in Edinburgh ruled the inquiry into Salmond’s behaviour was unlawful, and the Scottish Government admitted in court that the investigation was “tainted by apparent bias”, while it had breached its own procedures by appointing a lead investigator who had had prior contact with the complainers.

Salmond said he had been vindicated by the admission and called for the permanent secretary Leslie Evans, Scotland’s chief civil servant, to resign. Following the bitter court battle, Salmond received more than £512,000 from the Scottish Government to cover his legal costs.

That same month, Police Scotland’s investigation saw Salmond charged with 14 offences, including sexual assault, attempted rape, and indecent assault. The resulting court case, which took place over nine days in March 2020, heard evidence from nine women, including civil servants, a senior government official and an SNP politician, who made accusations ranging from unwelcome kissing and touching to sexual aggression.

After six hours of deliberations, Salmond was found not guilty of 12 charges of attempted rape, sexual assault and indecent assault, and one charge of sexual assault with intent to rape was given the verdict of not proven. The final charge was previously dropped by the crown during the trial.

Following his acquittal, in 2021, Salmond and other key figures within the SNP gave hours of evidence and testimony to a parliamentary inquiry, set up to establish whether Nicola Sturgeon and her allies had breached the ministerial code.

Although Sturgeon was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing, Salmond launched a fresh legal case against the Scottish Government in 2023, seeking damages and loss of earnings of £3 million.

In addition to the five-year political scandal sparked by the sexual misconduct allegations, Salmond also drew controversy for other behaviour, including fronting a weekly political talk show on broadcaster Russia Today. After premiering in 2017, the show was ultimately suspending following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA

© PA © PA

© PA © Andrew Milligan/PA Wire

© Andrew Milligan/PA Wire © Andrew Milligan/PA Wire

© Andrew Milligan/PA Wire