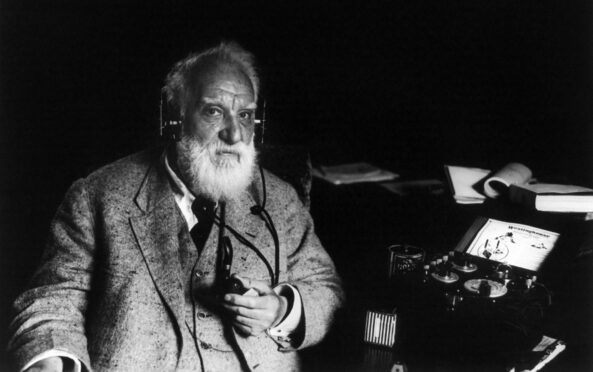

He is known around the world as “the father of the telephone”. But who among the billions with modern-day mobile phones will be aware that Edinburgh-born Alexander Graham Bell saw himself foremost as a tutor of deaf children, or that he considered his greatest achievement to be teaching them to speak?

Some experts say Bell’s method of “oralism” went on to dominate deaf education and led to a widespread campaign against the use of sign-language, its impact reverberating in the modern day.

Now his work with the telephone and with deaf people in his adopted American homeland, along with the rich and vibrant culture of the signing community, is being brought to vivid life in an ambitious debut fiction book by deaf author Sarah Marsh.

A Sign Of Her Own

The novel – A Sign Of Her Own – lands in bookshops on February 1, just weeks after England announced its first GCSE qualification in British Sign Language (BSL). The move brings it in line with Scotland which also offers an SQA qualification in BSL and was the first country in the UK to pass the BSL Act in 2015, enshrining the language in law, followed in 2022 by the rest of Britain.

In the novel we meet fictional deaf protagonist Ellen Lark, a former student of Bell in whom he had confided his dreams for the telephone. Now on the verge of wealth and fame he is being challenged by rivals and wants Ellen to support his patent claim. But she has a different story to tell – one of how Bell betrayed her and other deaf pupils in his pursuit of ambition and how he cut her off from a community in which she felt at home.

Sarah, a mum of two, told The Sunday Post: “A Sign Of Her Own is inspired by my experiences growing up deaf. As a child I was taught always to conceal my deafness. When I was a teenager, I took it as a compliment if ever I was told: ‘But you would never know!’ What people didn’t see was how much I was doing to disguise my deaf self, relying heavily on lipreading, hearing aids and guesswork. I wasn’t the only deaf person in my family. But it wasn’t until I was at university, and I met another deaf person my age, that I began to understand what this concealment was costing me.

“I finished a creative writing Masters degree, and started learning BSL, which opened up deaf culture and deaf history to me.

“I wanted to understand why my family’s deafness had been reduced to a medical history, where being deaf was an impairment that needed to be fixed. It didn’t have to be this way. Deaf people have a rich culture and heritage, rooted in sign languages.”

Her research included Harlan Lane’s When The Mind Hears and a chapter on Bell as an educator rather than inventor which she said “presents a very different perspective on his history”.

She also researched the “Visible Speech” technique used by Bell and his father that enabled deaf children to reproduce the sounds of speech “at great effort”. Bell – whose wife and mother were both deaf – later developed oralism. Sarah explained: “Bell believed in the superiority of speech over sign languages and campaigned extensively for articulation teaching.

“Most of his pupils were young women and, as I read more about them, I became interested in the ways in which they paved Bell’s path to the telephone.

“One even claimed that Bell’s idea for putting a voice in a wire came from their lessons. I wondered what it might be like to be one of these women, and how she might feel about the telephone and Bell’s claim to it.”

Bell’s impact

In 1874, Bell was in competition with Elisha Gray to be the first to invent the practical harmonic telegraph or telephone, but it was Bell who finally won the patent. An essay by US academic doctor Brian H Greenwald, published with the online Disability Museum, states that Bell believed oral skills were essential for social integration.

He cites Bell’s 1883 speech to the National Academy of Sciences, in which he states: “Bell noted that deaf people tended to marry each other, and he argued that if they continued this pattern, a deaf variety of the human race would form…” Greenwald further wrote that: “Bell identified signing residential schools, deaf newspapers, clubs, and associations as factors that encouraged the use of sign language and deaf intermarriage.”

He added: “Bell often recollected that his greatest contribution was not the invention of the telephone, but his work on behalf of oral education.” And he concluded: “By the early 20th Century, oral methods dominated deaf education in the United States” noting their “deleterious impact” on the culture of the signing deaf community “that continues today.”

London-based Sarah – who does not speak for the deaf community – said: “About 100 years later there was a report in this country that showed the impact of oralism. I was interested in writing about that turning point when attitudes were starting to change.”

Her absorbing debut – a first-person narrative that puts the reader firmly in the shoes of the deaf, deftly demonstrating the challenges of understanding by lipreading – was 10 years in the making. It was shortlisted for the Lucy Cavendish prize in 2019 and selected for the London Library Emerging Writers programme the following year.

She smiled: “This is a book about connections. Not the connections that Alexander Graham Bell hoped to forge with his telephone, but the connections deaf people made before a widespread campaign to prevent and ban the use of sign language.

“Bell always said his vocation was working with deaf people. He was a Victorian paternalist in lots of ways and that was one of the challenges of this novel: how do you judge someone against the standards of the time and now?”

Signs are good

Sarah says she hopes her book will give readers “an appreciation of deafness as a rich experience and as a way of being in the world.”

Legal and educational advances around British Sign Language and the presence of deaf personalities on stage and screen as well as representation in books are a major step in the right direction, she says.

The British Sign Language (Scotland) Act 2015 came into force in October 2015 and promotes the use of BSL in Scotland. Two years later the Scottish Government worked with deaf communities across the country to develop a national plan for BSL. It was published in 2017 and set out the steps it was taking between 2017 and 2023 to make Scotland the best place in the world to live, work and visit for people whose first or preferred language is BSL. The Scottish Qualifications Authority also launched a BSL Language Award at SCQF level 6, designed to appeal to both hearing and deaf learners.

The UK Government came later to the table with the The British Sign Language Act 2022 which received Royal Assent in April 2022. The new GCSE in BSL south of the border was announced in December and could be up and running by September 2025.

This week also saw ITV’s Love Island introduce its first deaf contestant, model Tasha Ghouri, who urged others to learn sign language. Strictly Come Dancing’s 2022 winner Rose Ayling-Ellis was its first deaf contestant. The EastEnders star had campaigned for England to follow Scotland and give sign language legal status.

A Sign of Her Own: How can a deaf woman speak out in a hearing world? By Sarah Marsh is published by Tinder Press

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Rii Schroer

© Rii Schroer © Find My Past

© Find My Past © BBC/Ray Burmiston

© BBC/Ray Burmiston