It seemed a road to nowhere but home for Alistair Moffat and his family but beneath their feet lay a highway into the past.

The Long Track on his Borders farm was once a busy medieval thoroughfare travelled by pilgrims, peasants and soldiers, and the former arts chief turned author has spent years excavating the lives of those who went before him by finding what they left behind.

To the former STV director of programmes and Edinburgh Fringe boss, the track is a “highway for our history, and a route to memory”. The award-winning writer and historian, a former rector of St Andrews University, moved to the farm from the capital in 1994, at that point not realising the seams of history running beneath his feet.

Its land has been occupied since prehistoric times but it wasn’t until a dozen years after he arrived that Moffat stumbled on his first ancient relic – a carved stone dating back 1,500 years. Later, after teaming up with detectorist Rory Low and Walter Elliot, 86 and a font of local knowledge, he began to unearth more treasures, finds that have led him to publish an eye-opening journal. The Secret History Of Here takes in a year in the life of the holding and all the years and all the lives that were there before.

Reliving how his search for “the ghosts of the past” began, Kelso-born Moffat said: “The first discovery was the stone, about the size of a square football. I hadn’t noticed it before. I picked it up and I immediately knew what it was; it was a million-to-one chance that it would be somebody who would recognise it.”

The stone was the top of a pillar on part of which the historian recognised two letters in the Old Irish language of Ogham. He contacted an academic at Glasgow University who immediately drove to the farm to validate his find which now sits in the National Museum of Scotland.

Moffat, the former chairman of STV who as director of the Fringe helped make it one of the most successful arts festivals in the world, revealed: “The Ogham stone is 5th or 6th Century, about 1,500 years old. You find them in Galloway, the Hebrides, in Ireland and some in Wales, but one had never been found as far east as this. At that moment, I thought ‘this place is old’.”

Despite the significance of his discovery, he went back to his busy routine of fixing fences, fertilising fields and chopping wood. However, everything was to change with the arrival in 2016 of his West Highland Terrier Maidie at the farmstead Moffat shares with his horse-breeder wife Lindsay, son Adam, daughter-in-law Kim, and their daughter Grace, five, sister to baby Hannah whom the family tragically lost to stillbirth in 2015. Moffat, who also has two grown-up daughters, Helen and Beth, said: “It wasn’t until I got my little Maidie that I started walking and looking around properly.”

His interest was further piqued when he joined forces with detectorist Rory. Moffat said: “He began finding things that amazed me. In the introduction to the book I write about Edward I’s army marching up the track, which is a fact because he paid his men at Selkirk Castle in July 1301.”

Into the writing Moffat weaved an imaginary Crusader knight. He said: “Rory found a sword pommel, which was attached to the butt end of a crusader’s sword.”

Evidence suggests the owner of the sword was Edward’s companion De Grandison from Savoy in northern Italy.

“It was almost certainly this man whose sword broke and he lost the pommel and 700 years later Rory found it,” said Moffat. Further finds included silver coins from the same period which, he says, “shows the men had been paid. Soldiers played gambling games, probably in the darkness around campfires and they lost them”.

Moffat began to trace a “chronological pattern”. He explained: “By the time we get to the 1500s people start to come on record.” Walter, his friend, was executor and heir to long-deceased Selkirk bakers Walter and Bruce Mason. They had been self-taught historians and archaeologists who had made their own finds on local farms, including the Moffats’, as well as collecting documents.

These were passed to the author who revealed: “Gibbie Hatly was a nearby farmer who left a detailed will in 1547 found by the Mason brothers. In it he leaves a pair of shoes and his best horn-handled stick to somebody called Andrew Fisher because Andrew helped him out of a burn he had fallen into when he was drunk. Stuff like that is just gold.”

And the discoveries just keep on coming. Of the most recent finds, Moffat revealed: “A big part of the farm is the deer park, which was a medieval deer park. The remains of Selkirk Castle are at one end but not on our land although the farm reaches almost right up to the ditch around the castle.

“Rory has been metal detecting for the past few weeks and has found some quite remarkable things. He found a metal tube made out of steel with handmade pins for pinning up ladies’ dresses inside. On the bottom of the tube is a seal – the woman who owned it would have used it to plunge into wax to seal things.

“One of his best finds was an American Zippo-type cigarette lighter. It was lost in one of the fields and it has the inscription on it ‘To Rita from Edek’. On the other side is the Polish army insignia. So this Polish soldier, Edek, gave the lighter to a local girl, Rita, and she lost it. The Polish Armoured Brigade were stationed in the Borders but went off when Europe was invaded, so did Edek leave Rita forever? We think he did because we tried to find Rita and him and we couldn’t.”

The author, who has been approached for the film and television rights to his book, muses: “What I discovered fired my imagination and made the small world I inhabit enormous, a place from where I could reach back through time, across millennia, so that I could take the hand of those who lived where we live 8,000 years ago. They saw the same skies I see. They were once me and I am them.”

The finds

Five intriguing artefacts found on or near Alistair Moffat’s farm

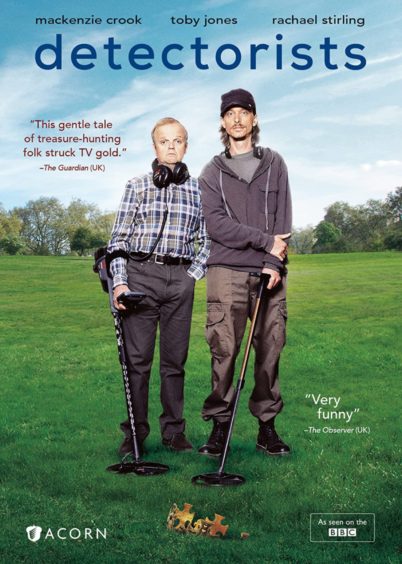

Sound of metal: TV’s Detectorists drive pastime’s rise in popularity

Digging up the past has never been more popular, thanks to TV shows such as Detectorists and Time Team.

Colin Toddy Irvine – who helped set up the National Council For Metal Detecting in Scotland and was its inaugural chairman – has seen a surge in demand for detectors and detecting events countrywide.

Irvine, 51, who is based in Falkirk and runs Metal Detecting In Scotland, for 20 years providing equipment, training and events for both land and sea searches. He said: “Metal detecting has taken off in the last four or five years, largely because of increased exposure in TV shows like Detectorists, Time Team and River Hunters. They encourage interest, as does the ease of information available on the internet.”

While Covid-19 restrictions took a toll on activities passion for the pastime persists, with many people taking up solitary searches in lockdown.

“There are people Scotland-wide who have been going out with metal detectors on beaches,” he said.

“Pre-Covid, we would average 70 to 100 people every Sunday at metal detecting events that take place between August and April. When we first started, we had about five. It’s a big increase.

“If I set up an event next week there would be 100 people at it but I have to wait until August when the farmers will be finished with the fields that we use.”

The dad of three has enjoyed his own bumper finds over the years including Neolithic stone axe heads and Bronze Age spears and swords but his most outstanding came in 2005 when he unearthed a medieval gold ring broach.

He said: “It was made from melted-down French gold coins and inscribed in Latin. It would have been worn by a lady to hold the scarf around her neck.

“It is now in the National Museum of Scotland. I got a £2,000 reward.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime find and it felt brilliant. I found it in Falkirk but I won’t tell you where…”

The Secret History Of Here: A Year In The Valley by Alistair Moffat is published by Canongate

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Supplied

© Supplied