History, at least the one recorded by men, painted them as sinful harlots, gold diggers, schemers or witches who caused feuds and fury and even faced assassination.

But the Honest Truth is there was far more to being a medieval royal mistress, author Julia Hickey tells Laura Smith.

Why write about medieval royal mistresses?

Medieval women were either virtuous or harlots. There was no middle ground. Royal mistresses faced censure, banishment, imprisonment and, on one occasion, assassination. I was intrigued to find out more.

Did you find it difficult to research?

Only women who achieved notoriety or impacted on a realm’s politics found their way into the chronicles. Piecing together fragments of information from other records and using circumstantial evidence creates as many questions as it answers.

Bellebelle, one of Henry II’s lovers, received the gift of a cloak, which was recorded in the royal accounts but it is impossible to find out more about her. Often the only way of knowing about the existence of a mistress was if they had a child who was provided for by its royal father.

What was in it for them?

A medieval king could sleep with whoever he chose. King John had a reputation for demanding to spend the night with the wives and daughters of his barons. More usually, an affair with a monarch ensured royal favour for the entire family.

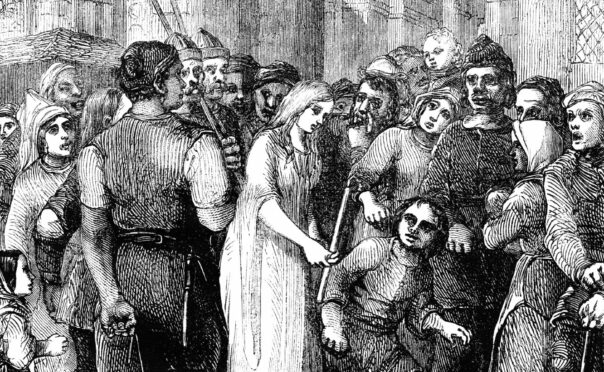

Difficulties could arise when the regime changed or during times of uncertainty. Jane Shore, mistress of Edward IV, was forced to walk barefoot through London wearing just her shift. Alice Perrers faced financial ruin and Katherine Swynford was forced into hiding because her lover, John of Gaunt, was so unpopular. All three women were accused of being witches.

Did royal mistresses play an important role at court?

The men who recorded events were monks who thought all women were sinful. Kings were expected to take mistresses but it was never an official role like it was in France. Even so, power and pillow talk go together. Katherine Mortimer and Alice Perrers were both reviled because their influence was too blatant.

Did many use the role to gain power?

King David II of Scotland was unusual in marrying his mistress, Margaret Drummond. He had already scandalised Europe by living openly with her during his estrangement from his first wife, Joan.

In England, Katherine Swynford, John of Gaunt’s mistress, was welcome at court but society was appalled when the duke married her. One reason for the outrage was Gaunt was Richard II’s regent and, until the king married, Katherine became the court’s first lady. She could be described as the most influential mistress in the book because her children were all legitimised and the Tudors were her descendants.

What about Katherine Mortimer?

Katherine Mortimer captured King David II’s heart while he was a prisoner in England. Like many other medieval mistresses, her origins are obscure. It was said the king could not bear to be parted from her on his return to Scotland in 1357. His nobles became jealous of her influence and arranged for Katherine to be murdered. By the following year, David was enamoured of a new mistress.

Did Margaret Drummond fare any better?

Margaret Drummond was no more popular than Katherine Mortimer. When David made her his second wife after Joan’s death, she set about enriching her own family. It helped cause a feud between the Stewarts and the Drummonds. Eventually the king tried to have the union annulled after she failed to provide him with a legitimate heir. He died before a ruling was issued on the case.

Are any men included?

Queens did not have the same opportunities for extramarital affairs. They were supposed to be beyond reproach and penalties for transgression were severe. However, Isabella of Valois, wife of Edward II, took Roger Mortimer as a lover when she tired of her husband’s dependence upon favourites like Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser. Chroniclers of the time speculated about the nature of Edward’s relationship with both men.

Medieval Royal Mistresses: Mischievous Women Who Slept With Kings And Princes by Julia Hickey is published by Pen and Sword

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe