IT is Donald Trump’s favourite insult while others insist it helped him win the Presidency.

But fake news – despite being chosen as Word of the Year by Collins Dictionary last week – is nothing new.

For hundreds of years, millions were convinced by one almighty alternative fact – involving an entire new world of 50 million people and untold riches.

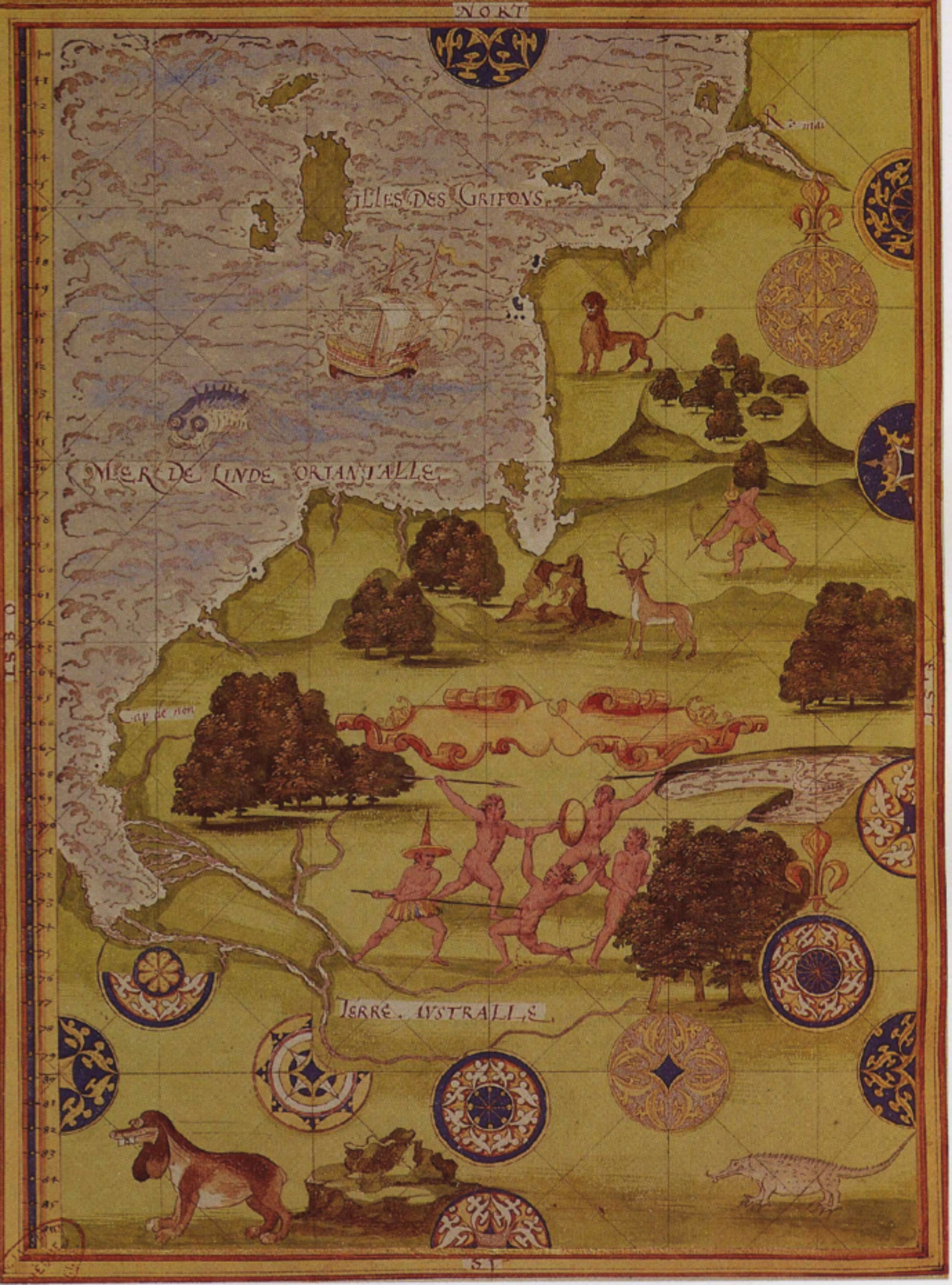

It was claimed to be a land of giants and there were reports of a race of headless, eyeless creatures, with a hole at the Pole for the Southern Lights to shine out. And its ultimate debunking by Captain James Cook in the 18th Century was such a blow to respected Scots geographer Alexander Dalrymple that it led to a bitter fallout between the pair.

Broadcaster and author Vanessa Collingridge is so fascinated by the incredible tale that she has just completed a PhD on it at Glasgow University and is to explore the amazing myth of the Great Southern Continent at a talk this month.

“This really was the biggest of fake news stories,” said Vanessa, who lives in Lochwinnoch.

“Fundamentally, it was about what there really was down in the southern hemisphere.

“Since the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans it was felt there must be something to counterbalance all the land in the northern hemisphere or else the world would be top-heavy. So for 2000 years this land was imagined, given coastlines and great civilisations.

“A famous map had it taking up pretty much the bottom third of the world.

“It was so detailed that people absolutely believed that this land was real.”

After the discovery of the New World and the Americas in the 16th Century, finding it took on even greater significance.

“The stories were that it was an amazingly rich place,” said Vanessa. “There were diamond and gold mines and fantastically fertile soil. It was all very lovely and Utopian.”

Accounts of what lay to the south were published in magazines.

Australia was believed to be a part as was New Zealand but Abel Tasman, who discovered the island country, didn’t investigate further as many of his men were murdered.

It fell to Captain Cook on his two epic voyages on the Endeavour and Resolution between 1768 and 1775 to change everything.

“James Cook added roughly about a third of the globe to the world map,” said Vanessa. “He charted everything from the far northern reaches of the Pacific and Arctic Oceans down to the Antarctic. He really sailed off of the known map of the world.”

Cook’s sealed secret orders tasked him with finding the Great Southern Continent but after his second voyage, when he went further than ever before, he came home to report there was no such thing.

“Some 2000 years of speculation ended in an instant,” said Vanessa. “But it didn’t meet with widespread approval.

“Dalrymple said Cook was lazy and simply didn’t look hard enough. The pair of them had a real go at each other.

“But what’s fascinating is that right up until Cook’s final journals were published there were still fake news reports saying he’d discovered a Great Southern Continent full of diamond mines.

“So fake news really isn’t new at all.”

Vanessa will be at Waterstones, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow at 7.30pm on November 15 as part of a series of Inspiring People Illustrated Public Talks being run by the Royal Scottish Geological Society.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe