The encounter may have been fleeting and nearly a decade ago but Natalie Sanders will never forget the thrill of spotting two male orcas power through rolling waves off the coast of north-west Scotland.

It’s a vivid memory that still gives the marine expert chills, especially as it now has an even more profound meaning given the tragic fate of those two native apex predators and their pod.

Sanders had her first sighting of wild orcas in 2014 while aboard The Silurian, the research boat of the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust, a Mull-based marine charity. The two male orcas, Comet and Aquarius, were members of the west coast community, the only pod believed to be entirely native to the British Isles.

“Everyone wants to see orcas but very few do so to see them off the coast of Skye was thrilling and miraculous. It was like the Holy Grail,” said Sanders, 39. “I’ve kayaked next to humpback whales that were much bigger but the orcas were just incredible.

“They’re so powerful and robust but also incredibly elegant and agile. They stayed near us for an hour then vanished. I can still remember it as clear as day.

“It’s also sad as Comet, who famously swam up the River Foyle into the heart of Derry in pursuit of salmon in 1977, has not been seen since, so it was one of the last sightings of him.”

It proved to be Sanders’ only glimpse of the west coast community of orcas, a small family predominantly found in the waters around the Inner and Outer Hebrides.

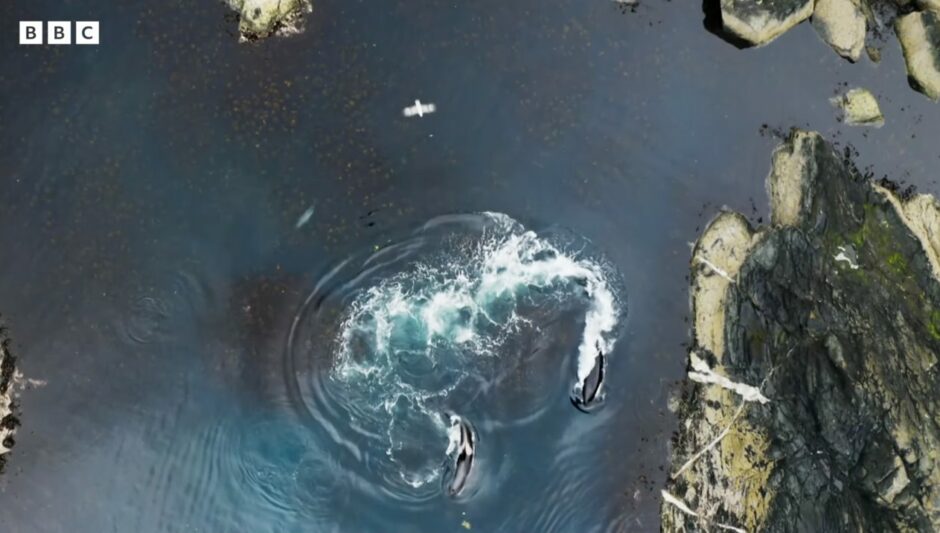

Today the pod is on the edge of extinction with its numbers dwindling from 10 to just two male orcas known as John Coe, identified by the distinctive nick missing from the base of his dorsal fin and first spotted in 1980, and his companion, Aquarius. Both are believed to be more than 50 years old, twice the average age-span and now too old to mate.

Sanders’ new book, The Last Sunset In The West, tells the story of Scotland’s vanishing west coast orcas to raise awareness of how we can preserve other pods around the world, including the Northern Isles community, a family that migrates between Iceland and Shetland and Orkney.

“We have this incredible wildlife on our doorstep but their existence isn’t well known as they are rarely sighted,” said Sanders.

“They are a unique group with a powerful message. I wanted to tell the west coast community’s story while it still exists.”

The Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust has been documenting the pod’s behaviour since 1994. “There were thought to be more in the 1980s but only 10 were ever catalogued,” said Sanders, whose book introduces past and present members of the pod: John Coe, Nicola, Comet, Moon, Lulu, Floppy Fin, Puffin, Aquarius, Occasus and Moneypenny.

“Little is known about the west coast community,” said Sanders, who has studied the whales for 10 years including encounters with other wild orcas in British Columbia.

“They are believed to be genetically unique to other orcas in the north-east Atlantic and are more closely related to those in the Antarctic, so they could be a splinter group.

“They tend to predominantly spend their time in the Hebrides but will travel around in search of prey so have no real fixed pattern. They’re just constantly roaming for the next meal and have been seen around Ireland and more recently the English coast near Cornwall. They’ve only ever been seen in UK waters.”

Orcas, also known as killer whales, are the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. Around 50,000 live and hunt across the world’s seas. Recognisable for their black and white colouring, they are strong, fast and voracious predators that form close family bonds.

Yet they are also vulnerable and under threat, said Sanders: “Many populations around the world are struggling like the west coast community and extinction is a real threat for them. We’re seeing rapid declines with 50% at risk of extinction in the next 100 years.”

Key threats include marine pollution, habitat degradation, entanglement in fishing lines, underwater noise pollution and dwindling prey due to over-fishing.

The demise of the west coast community is largely due to infertility caused by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), toxic chemicals banned in the UK since the ’70s.

Lulu, a female found on the shores of Tiree in 2016, died of starvation after becoming entangled in fishing lines. An autopsy revealed she had reached reproductive age but had never produced a calf. She was the world’s most toxic orca with PCB levels 100 times greater than what is deemed harmful to marine animals.

“There’s been a catalogue of stresses that has led to this pod’s decline,” said Sanders. “Lulu had never conceived and was clearly inbred. As their population size decreased, they had fewer opportunities to mate outside their family unit, which stays together for life. The levels of PCB in her blubber also impacted her immune system and fertility. A male orca recently washed up in Scotland with high PCB levels so this is still an issue.

“Underwater noise is another threat. Even in the Hebrides, there are fish farms with underwater acoustic deterrent devices to drive away seals and military testing twice a year using sonar. The noise can drive orcas from their feeding areas, affect their ability to hunt, chase away prey and cause permanent hearing damage.”

There is no way to save the west coast community pod from extinction. Their fate, according to Sanders, is a stark warning of the need to protect the world’s remaining orcas.

She said: “We see orcas as hugely robust, powerful creatures at the top of the ocean’s food chain with nothing that can harm them but that’s far from the truth. The whole species is facing huge pressures now. If our apex predator is under threat, that’s a real wake-up call for what’s happening in the rest of the ocean.

“Only a fraction of PCBs have been disposed of so we need a global, unified approach to dealing with PCBs. Entanglement in fishing gear is a deadly threat to all marine animals so we need ways to work in harmony with the fishing industry. There are also better alternatives to fish farm acoustic deterrent devices, which are banned in Canada, such as heavier nets covering sea pens to prevent predation.”

Sightings of the Northern Isles community, recently featured in David Attenborough’s BBC nature series Wild Isles, have become more common around Shetland and Orkney, including orca calves.

Sanders said: “They’re being seen in increasing numbers now, which is encouraging. A silver lining is that as one population’s dying off, we’re seeing an increase in another.”

Sanders, who works in the climate change research unit at Imperial College London, remains thankful for getting the chance to see members of the now vanishing Scottish orcas in the wild. She said: “They’re highly intelligent, loyal and socially complex; capable of companionship, compassion, empathy and grief, as well as being very playful and highly skilled hunters.

“While it’s too late to save the west coast community, hopefully we can use that knowledge to save orcas around the world facing similar threats. We need to cherish the populations that are doing well by fostering a safe environment for those that are thriving.”

The Last Sunset In The West: Britain’s Vanishing West Coast Orcas by Natalie Sanders published by Sandstone is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA

© PA © BBC

© BBC © BBC

© BBC