When Anne Kershaw was first swept off her feet by a polar pilot, she didn’t know if Antarctica was to the south or the north of the globe.

The former stewardess also didn’t know that her life was about to become dominated by the icy continent – taking over the world’s only private airline to the South Pole after her husband was killed in a crash.

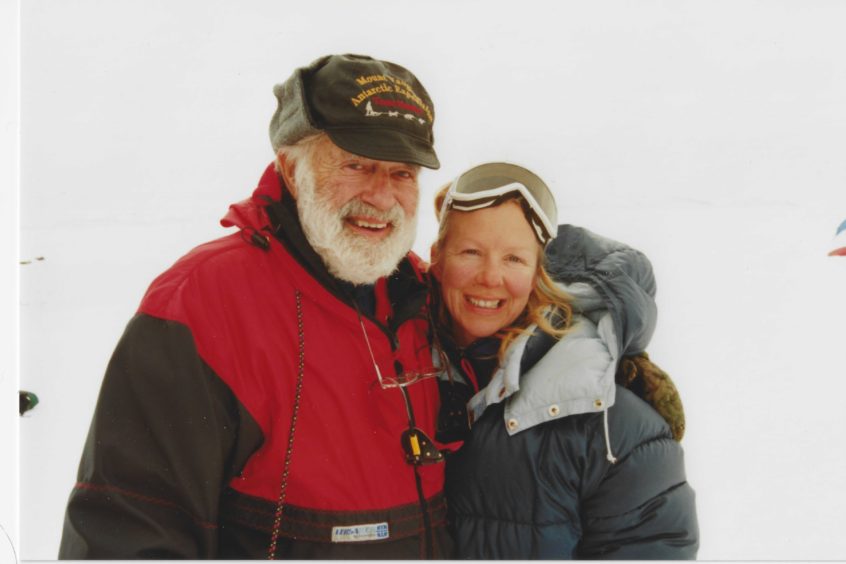

While she could have been forgiven for never wanting to think of the place ever again, the determined Scot instead made it a mission to make it as safe as possible. Now, after 30 years of flying the likes of Sir Ranulph Fiennes and Michael Palin, as well as taking the world’s leading explorers and most eager young scientists, the Anne has one last great adventure planned for Antarctica – to save it.

While it might have been the cause of her greatest heartbreak, Anne has launched a new drive to help preserve the world’s last wilderness.

Glasgow-born Anne, 60, now lives in Nevada, where she raises her four teenage children and runs the Polar Commitment Foundation, a campaign to encourage governments to work together to reduce impact on the continent by sharing resources and logistics.

It’s a long way from the days when she lived in 1980s Hong Kong and worked cabin crew for Britannia airlines, where she met a charismatic English pilot.

“I didn’t know a thing about Antarctica,” she said. “I met Giles and here was this man who was one of the pioneers of flying down there and I was like, ‘Is it at the top, is it at the bottom?’. It was only until after he was gone that I really learned about it, and the first thing that hit me was that he’d died there and there was nobody there who could save him.”

When Anne first visited, she described her 28-year-old self as being more about make-up and heels than thermals and crampons, and had never done any kind of camping when her new husband whisked her away in 1988 to his air base at Patriot Hills, Antarctica.

A veteran of the British Antarctic Survey flights, Giles was a keen adventurer, working with the likes of Sir Ranulph Fiennes. And he and a group of pals had formed Adventure Network as a way to help get them south faster.

Anne said: “He and I went down there on one of our first trips after we were married.

“It was so quiet you could hear the snowflakes hit the snow. There were no people, no trees, no animals. It was so quiet and I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God this is so beautiful’, and I knew why he loved it so much. I remember not understanding any of the risks or dangers or the violent weather you could have there and my philosophy was they all know what they were doing so I didn’t feel any fear because I had no idea what I was getting myself into.”

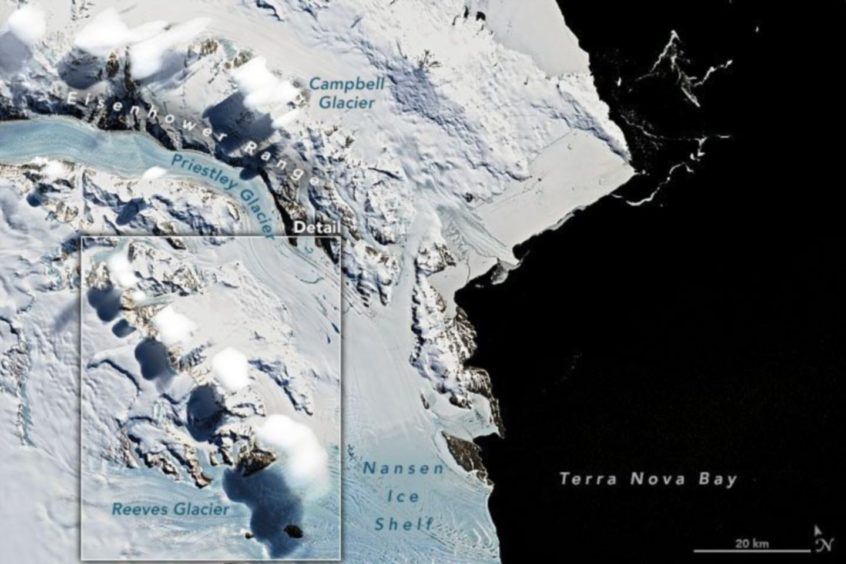

Two years later, however, she got the call every explorer’s partner dreads. But she was so confident of Giles’s skills and experience that, when told he had died in a microlight crash on the Jones Ice Shelf, she didn’t believe it. “He never made it sound like it was a dangerous thing he did and I just assumed he knew what he was doing and he was very meticulous with his flying. You’re young and planning a family and you just think he’s invincible and he’s done this for years and will go on forever.

“But when it sinks in, it’s this enormous blow you think you’re never going to recover from.”

From that moment on, Anne kept being haunted by the idea that there had been nobody there to help him, and was determined that nothing like that would ever happen again.

Near where Giles died, the massive Mount Kershaw is named in his memory. She wanted Adventure Network to be a living tribute to him.

She started work in 1991, determined to have a say in making safer the airline she now part-owned. The flights left from Punta Arenas in southern Chile, but her first duties saw her parked in the Miami office. Anne admitted: “I was doing a lot of running. Running away from the sadness and the grief and trying to fill my days with anything that kept me busy.”

She proved a success and soon took over management of the airline. She said: “I thought if this was going to be a company that operates in the Antarctic, it has to be safe. So, over that period of time, we had the best pilots, the best aircraft and the most experienced guides. We went from being this tiny little company that took people to Mount Vincent to being the largest air operator next to the American government.”

Even with the most stringent safety rules, flying to the Antarctic is one of the trickiest tasks imaginable. Back in the 1990s, there was little of the weather tracking or satellite phones enjoyed by modern flyers, and fuel reserves meant that once you had flown halfway there, there was no turning back no matter how nasty the weather might turn.

Added to notoriously choppy winds was a four-mile-long, mainly ice-covered runway, which was, as Anne said, “at the end of a mountain range and the hope is that the aircraft is going to stop”.

The new-look company helped rescue Giles’ former expedition crewmate Sir Ranulph Fiennes when a mission went awry, while Anne also enjoyed some TV stardom when Michael Palin appeared to hitch a lift for the final step of his Pole to Pole series in 1992.

“Ran’s a good friend and it’s always been great working with him. Michael Palin did huge things for us, because all of a sudden people realised you could actually get there. He was one of the first celebrities to do that – and a wonderful human being.”

In 2003 – the year she was made an MBE for her services to aviation in the Antarctic – Anne left Adventure Network and turned to charity work, teaming up with explorer pal Robert Swan to run 2041. The group, named after the year the Antarctic mining treaty expires, is dedicated to helping young people learn more about the continent.

By that time living in the US, she remarried, to explorer Doug Stoop, and had son Tyree, now 19, and adopted Than, also now 19, from Thailand. The couple are now divorced and she has since adopted Ethiopian-born orphan twins Zek and Habte, both now 16, as a single mother herself.

Two years ago, after more than a decade with 2041, Anne decided it was time for one more career change and so she set up Polar Commitment Foundation with a mission to get governments to save money and share resources for better operations in Antarctica.

“I’ve gained a lot from Antarctica and it was time to give back. My idea was to work with governments to encourage them to share logistics – most of them don’t do that – so they can save money and put the money back into science. The more I’ve worked with governments, the more I realise there is a lot of room for change – good change. With the Polar Commitment Foundation, I believe we can be the catalyst for that change.

“The hook is, there are seven continents on Earth, can we save one of them? I feel like we can make a difference.”

Anne has now been to Antarctica more than 50 times, and feels the presence of Giles every single visit. “Once I’m on the continent, I get a little space for myself and it’s this incredible feeling which takes me right back to when I was first married and going down there with Giles.

“I felt at home but you have to remember it’s somebody else’s home and you can’t let your guard down.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © NASA Earth/ZUMA Wire/Shutterstock

© NASA Earth/ZUMA Wire/Shutterstock © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied