SINCE the arrival of the first convict fleets in 1788, Scots have played an integral part in the shaping of modern Australia, including the very naming of the country.

But while the past achievements of certain Scots have previously been hailed as “legendary” in the great Southern continent, new evidence is coming to light which places these same Scots under intense scrutiny.

The current debate to change the date of Australia Day (26 January) – which falls on the day British authorities formally created a ‘new’ settlement in New South Wales – is one of the key drivers casting a dark shadow over the Scots who helped to colonise the country and bring murder and displacement to the country’s Indigenous population.

Statues of Captain James Cook, the son of a Scottish labourer who charted and claimed the east coast of Australia for Britain have been vandalised. And there have been calls for the statues of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, the Isle of Mull-born Governor of New South Wales to be removed, and for streets, rivers, ports, harbours, banks, and universities named after him to be changed.

Australia Day is celebrated as the day the Union Jack was first raised in the country on 26 January 1788, marking the new era of British colonialism. While this is a day of celebration for many Australians, for the country’s Aboriginal population and their supporters, it is often referred to as ‘Invasion Day’ – the day that marked the beginning of the end of Aboriginal rights and country.

Until recently, like Cook, Macquarie had been hailed in Australia and Scotland as a pioneer and a hero, who from small beginnings on the small Isle of Ulva off the coast of Mull became a monumental force behind the establishment of the Australian colony. He built roads, buildings, schools and in 1818, helped give Australia the name we know it by today. An inscription on his mausoleum on Mull still proudly claims him as the ‘Father of Australia.’

But it has been uncovered his legacy is also one mired in Australian Aboriginal genocide and abuse, the results of which are likened by many Aboriginals to the events of the Holocaust.

While many Australians believe statues of Macquarie down under should be taken down or altered, the custodians of Macquarie’s Mull mausoleum in Scotland say the inscription could be looked at as a product of its time.

Archivist Georgia Satchel on behalf of Mull Museum Committee said: “Whilst actions of an individual may be seen in a different light from one generation to the next, we still record those reactions, even if we now disagree with them.

“But we are concerned with presenting all the available material we have about historic figures/events so that people may draw their own conclusions.”

Historian, visiting research fellow at Glasgow University and author of The Scots in Australia 1788-1938, Ben Wilkie, is one of the researchers challenging the narrative of Scottish ‘heroes’ like Macquarie, and bringing to light the atrocities committed by Scots against Australia’s First Peoples.

“The Scots and the Irish migrants to the various New Worlds did very well for themselves, and in part this was because they participated in a system that, at best, was gargantuan theft – and, at worst, genocide,” he said.

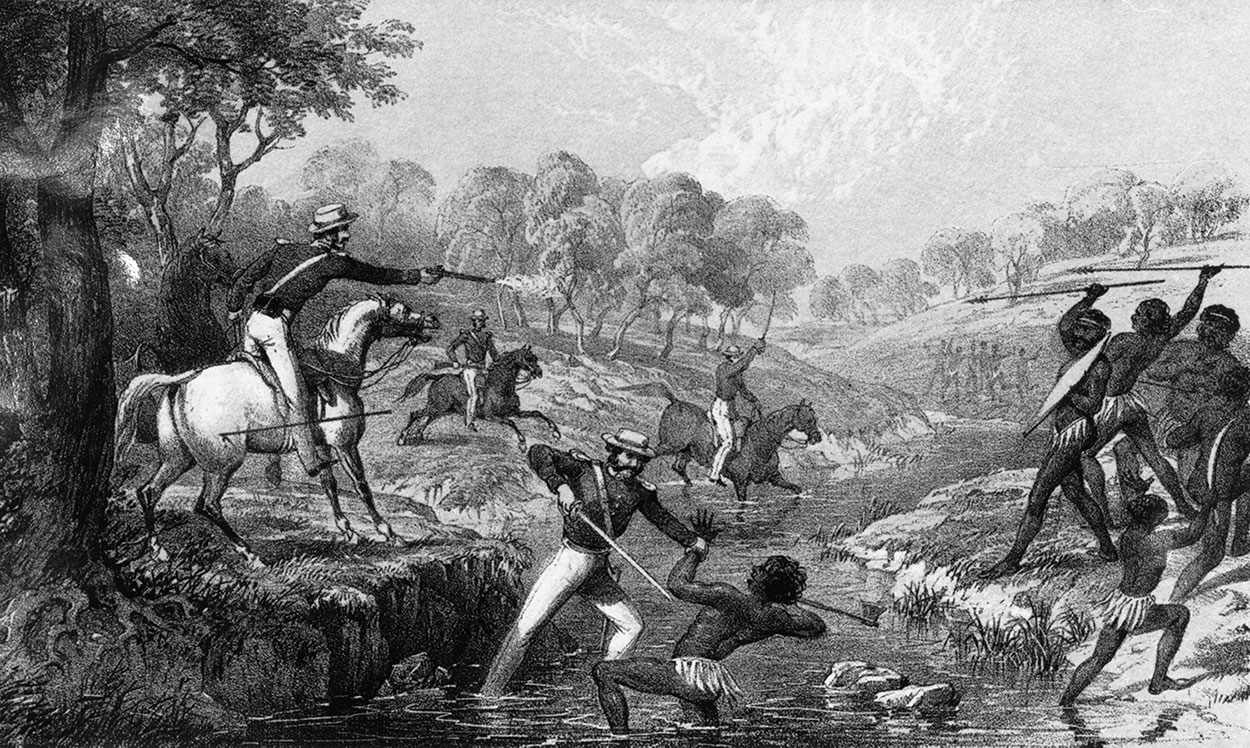

“While Captain James Cook primarily laid the groundwork for British colonisation in Australia, Macquarie ordered reprisal attacks against Murningong and Gandagarra people near modern-day Sydney in April, 1816. It was, in his own words, a war against Aboriginal Australians.”

Macquarie’s 1816 reprisal stated: “If they…make the least show of resistance, or attempt to run away from you, you will fire upon and compel them to surrender, breaking and destroying the spears, clubs, and waddies of all those you take prisoners.

“Such natives as happen to be killed… if grown up men, are to be hanged up on trees in conspicuous situations, to strike the survivors with the greater terror… you will use every possible precaution to save the lives of the native women and children, but taking as many of them as you can prisoners.”

In what he called a mission to “rid the land of troublesome blacks,” Macquarie’s men, accompanied by Aboriginal trackers, also forced a group of native Dharawal men, women and children over a cliff near Appin in New South Wales, then shot and hung the survivors (including the group’s leader) in trees to terrorise the other Indigenous people. After this, heads were hacked off as trophies that ended up at the anatomy department at Edinburgh University. The heads were returned to Australia in 1991.

Macquarie was also the instigator of ‘Native Institutions,’ which paved the way for Indigenous children to be forcibly taken from their families to adopt ‘Christian ideas and civilised ways’ and to make them into servants for white settlers “for their own good,” in Macquarie’s words. This legacy of forcing children into institutions to stamp out Aboriginal culture continued until the 1970s in what Indigenous Australians now mourn as the ‘stolen generations.’

Thanks to this emerging history, and the 231 years thereafter of Aboriginal murder, abuse, lack of rights, removal of land and the forced institutionalisation of native children, the holiday that Macquarie originally created is now one that many Australians are becoming less and less comfortable celebrating.

Towns like Fremantle and counties like Barebin have renounced 26 January as a date of celebration, while the debate rages on whether the entire country should continue to honour this day in the future and whether statues celebrating Macquarie should be allowed to remain.

Many politicians, including Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, have supported the date however, stating on Wednesday they have no plans to officially change it. The announcement came after a survey by the Institute of Public Affairs showed 71 per cent of the population wanted to keep 26 January as Australia Day.

But foundations like Reconciliation Australia (RA) say it remains impossible for Australia Day to serve as an inclusive national occasion as long as it is held on a date that some Australians celebrate while others grieve.

RA’s co-chair, Professor Tom Calma says it is important for all Australians to fully engage in the history of 26 January and what it represents in order to progress positively.

“It’s not about trying to lay guilt on individuals but it’s about trying to make sure that our future, our children and Australians generally, have an understanding of the history of Australia,” he said.

“Australia’s history didn’t start in 1788 but it goes on well beyond that. And there’s a lot to recognise and celebrate. But also there’s a lot in our history that’s very dark, that we need to expose to ensure that these sort of atrocities never happen again.”

As for the legacy of Macquarie, Ben Wilkie believes facing his history head on is also the right thing to do for Scots and Australians alike.

“I think often that we learn nothing when we sweep the bad parts of our history under the carpet,” he said.

“For example, plaques can be, and have been, added to existing monuments that explain the individual’s contribution to dispossession and colonisation.

“An information board or plaque added to Macquarie’s Mausoleum would be an important gesture to acknowledge that he was a significant figure in Australian history and that he played a role in the dispossession of Indigenous Australians.

“Scots were some of the most active and enthusiastic participants in what is described as ‘the greatest single period of land theft, cultural pillage, and casual genocide in world history’.

“And if Scotland is to move forward as a global nation, this history must be recognised.”

Black-birding: Islanders kidnapped for plantations in Australia in forgotten South Seas slave trade

Thanks to the emergence of documentaries, exhibitions and popular culture focussing on Scotland’s place in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, our history concerning that specific practice is becoming increasingly well known.

But Scots also played a role in a lesser-known slave and labour trade – one which was still operating after the abolishment of American and Caribbean slavery, in 19th and 20th century Australia.

‘Black-birding’ became the name given to the practice of white colonialists sailing to the South Sea and Torres Strait Islands, kidnapping native peoples and forcing them to east Australia to work on cotton and sugar plantations for little or no pay. This practice continued until the early 1900s.

John Munro Mackay from Inverness-shire was one of these ‘Black-birders,’ owning plantations that employed this Pacific Island labour. The city of Mackay in east Australia is named after him, though the descendants of those affected by the trade believe that name should be changed.

Clive Moore, a Professor of History at Queensland University and convenor of the Solomon Islands Information Network was born in Mackay and believes Australian South Sea Islanders have never received social and economic justice for the indignities done by transporting them to Australia.

“The labour trade is often equated with American slavery… and certainly Australian South Sea Islanders see it that way,” he said.

“Scots are all through this labour trade as Captains and Government Agents.

“The stereotype of the noble explorer which [Mackay] carefully cultivated 150 years ago remains undiminished. And his role in the labour trade and as a plantation owner is barely known.

“Mackay was fully involved in this shameful era, a part of Australian history many prefer to forget.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe