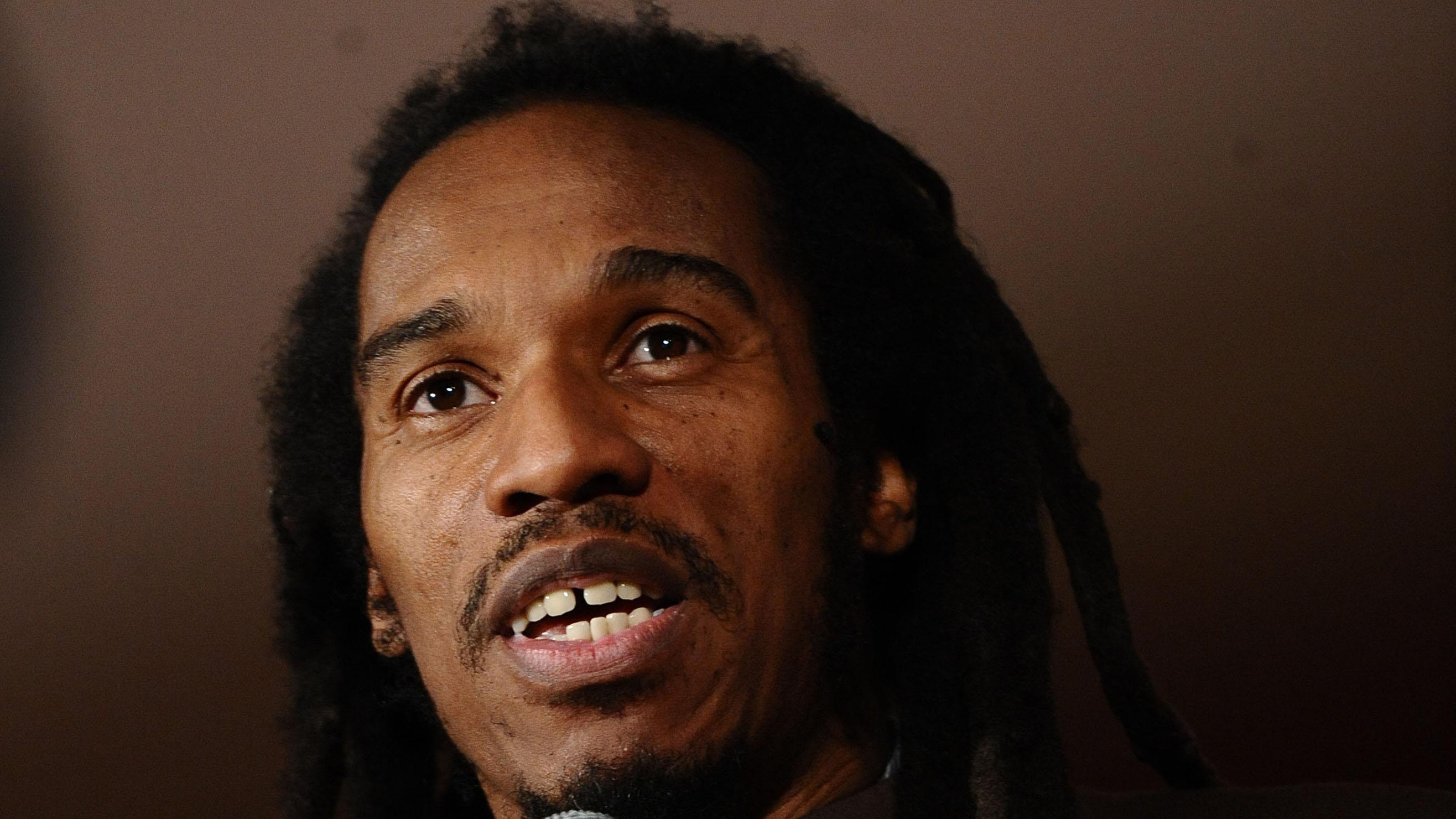

Poet and musician Benjamin Zephaniah can’t wait to dip his toe across the border as he plays this year’s Knockengorroch Festival.

The acclaimed lyricist, who headlines with his band the Revolutionary Minds, has a special place in his heart for Scotland – even once eloping to East Kilbride with a girlfriend in the 80s.

“I just love that word Knockengorroch,” he laughs as he chats to The Sunday Post. “Since the tour’s been announced online I’ve had a lot of people asking when I’m coming to Scotland and this is just a little sojourn north of the border.

“Hopefully we’ll do some more next year. I love playing in Scotland. I used to spend a lot of time in Edinburgh and lived in East Kilbride for a while… it’s a place that’s always getting the mickey taken out of it.”

Birmingham-born Benjamin, 61, treats all trips north with the respect of visiting another country when crossing over the border.

He reckons if he was Scottish he’d vote in favour of independence, and that Scots are getting a ‘raw deal’ when it comes to Brexit.

And the high regard in which our national bard is held in impresses the man often himself labelled a ‘people’s laureate’.

“I know it’s a little bit stereotypical like going to Jamaica and talking about Bob Marley, but Scotland has a poet that they revere so much in Rabbie Burns,” he says. “Most people can quote him, and even drunk Scots can still recite one of his poems!”

At Knockengorroch, Rastafarian Benjamin is joined on stage by his band, the Revolutionary Minds, and promises a set of heavy dance reggae.

“There’s a lot of bass but with a social conscience in the lyrics,” he explains. “I’m very much into the singalong, or more like a chant-along, which will suit the Scottish crowds. I ask people to think and dance at the same time.”

Billed as a ‘world ceilidh’, the festival is something of a melting pot of music from home and abroad.

“It’s lovely, that’s what I really like about it,” Benjamin says. “There’s this term world music which I sometimes feel a little bit uncomfortable with because all music is in the world. You shouldn’t presume that western music is music and everything else is world music.

“This festival has a very global approach, there’s African music to Gaelic music. I just love that mix and saying to the audience open up your mind – not all music works to 4/4 beat and not everyone sings in English!”

The multi-cultural blend that forms the line-up for the festival is a fitting place for a man known for work which is powerfully charged with social commentary.

Growing up, Benjamin was a part of gangs and spent time in borstal and prison. A difficult childhood saw both he and his mother beaten by his late father.

But once he found a gift with words, he swapped the criminal gangs for gangs of a different kind – those armed with paint brushes and pens – publishing his first poetry collection aged 22.

And, several decades on, he still firmly believes it’s important to represent himself and create art in a way that cuts through the politics and reaches out to people to tell the story of his experience.

He says: “From the tradition that I come from, music has always been about social commentary. Early reggae is all protest music. When Bob Marley was asked why he wrote political songs he didn’t understand the question, he said he just wrote songs about his life and experiences.

“For a lot of black people living in the western hemisphere, our experiences are political, we can’t help it. We just start writing about our lives. I think it’s necessary and important that we tell our story – if we don’t, some so-called expert will come and do it for us.”

On the subject of racism, Benjamin says that it would be wrong to say it’s at a level comparable to the 70s and 80s, but he has been saddened by statistics showing the rise in racist attacks in the years following the Brexit vote.

He says: “I’ve lived through the 70s and 80s, but I was really shocked at the racism I’ve experienced recently. A lot of it is just people shouting out of cars – they always shout things when moving away from you.

“I just find it very sad that we’re still having to deal with it, and therefore I’m still having to talk about it.

“The rise of the right generally is really sad. I thought that when I got to this age I’d be retired and we’d have a bit more peace, love and harmony. It’s not happening anywhere in the world. People are not pulling together as I thought they would be by now.

“I could be called me naive for that – it’s a bit like the John Lennon line ‘you may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one’ but I’m really not the only one!

“There’s a lot of us who thought things would be sorted out by now. When we came into the new millennium we thought we thought it would progress but we’ve taken so many steps backwards.”

A place where racism has reared its ugly head prominently in recent months is in football. A series of incidents at grounds across the country have seen black players suffer abuse many thought was consigned to the past.

Benjamin, an Aston Villa fan, recalls the days where he would have to stand among thousands chanting loud, racist songs on the terraces, with some grounds even allowing the National Front to run recruitment stalls.

“Those days are gone but we’ve still got to deal with both racism and homophobia,” he says. “I go to football a lot and sometimes I’ve heard people on the verge of saying something racist but they have to reign it in and control it.

“The reality is that, when we bring in laws and fine and punish clubs, you can only do so much. We have to teach and educate people generally that we live in this country that we’ve got to live in together and racism has no place in it.

“You can make new laws quite quickly but it takes time to change the attitudes of people.”

Benjamin believes the marked increase of racist incidents in the game is a reflection of a shift towards the right in society generally.

“The extreme right feel empowered,” he says. “They have their slogans ‘Make Britain Great Again’ or ‘Make America Great Again’ and they feel its their time.

“And when you see mainstream politicians courting extreme racists, they feel that they have friends in high places.

“I saw a guy saying all these racist things towards a nurse in a hospital the other day because he couldn’t get his medicines on time. He kept saying ‘this is England’ before going back along the queue he’d jumped and finding the white people and saying ‘that’ll teach them, we’ll soon get rid of them’. He felt emboldened. They really think this is their time.

“There’s a lot of us that are shocked that we’re back here. I was talking to a friend the other day, a white woman who lives in rural England, and she’s having problems with her partner.

“He’s sitting at the TV giving Raheem Sterling racist abuse when he scores three goals and she’s flabbergasted. She says she doesn’t understand racism and I said, of course you don’t, that’s why you’re not a racist!

“It’s something that doesn’t make sense logically. You get older people who call black people coloured, but they’re racist through ignorance. That’s slightly different, they’re using the wrong terms and stuff like that.

“I can understand that, but when you have someone that just hates black people, loves football but hates black people in football, you wonder how it’s logical. Look what black people have done for British sport.”

Benjamin believes some of the problem stems from the way we do politics – and that’s the reason he’s a revolutionary.

“I don’t say that I have the answers, I just know we’ve got to do things differently,” he says. “So I try to inspire people to think differently. That’s the best I can do. There’s a lot of people who recognise the political system is messed up but I don’t think the people on top are being very imaginative.

“There’s a big disconnect between people who experience things and people who actually administer our lives. One of the problems with politics is that if you want a job as a politician, you’re probably the wrong person for the job. If power is the thing you want, you’re probably the wrong person to have power.

“The everyday people I look at who do great things, I think should be leaders, but they’d shy away from the job. They run soup kitchens and youth clubs, but they should be running the country!

“I have travelled the world and the one thing I’m absolutely convinced of is that in left wing countries, right wing countries, Islamic countries, dictatorships one thing that people keep saying to me is that their politicians don’t represent them.”

Benjamin will be a familiar face to fans of drama series Peaky Blinders.

He features as a regular guest star in the role of Jeremiah Jesus.

“The character I played is based on a real person,” he says. “When Steven Knight was writing the character he said that he thought of me. I come from a family that were in the church so I knew exactly how to play the role.”

CONFIRMED: #PeakyBlinders will return to @BBCTwo in 2019. ? pic.twitter.com/YskoNrhezc

— BBC Two (@BBCTwo) December 20, 2017

Benjamin says he’s delighted to be a part of the hit show, which returns for its fifth series later this year.

“I love it and I’m really proud of it,” he adds. “I’m from Birmingham and I’m really proud of the city. There’s not much TV that comes from here so it’s really close to my heart.

“Every year I go, film a few days with Peaky Blinders and then it’s shown all over the world. I sit in my hotel room and listen to it in German and Chinese! It’s great.”

Knockengorroch World Ceilidh, 23-26 May, knockengorroch.org.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © BBC/Caryn Mandabach Productions Ltd/Tiger Aspect/Robert Viglasky

© BBC/Caryn Mandabach Productions Ltd/Tiger Aspect/Robert Viglasky © PA

© PA