It was a rousing speech which gave a stark warning to Vladimir Putin and reassurance to the country he invaded a year ago.

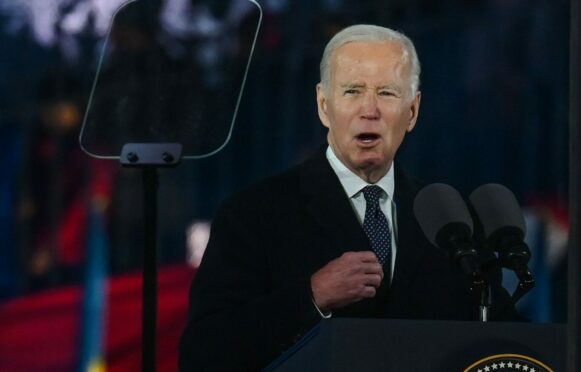

After visiting Kyiv on Tuesday, US President Joe Biden travelled to neighbouring Poland and, in an address to a crowd in front of Warsaw’s Royal Castle, he promised western support would not falter and that Ukraine would prevail. His speech rallied a nation where the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is huge and ongoing.

As Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine last February, more than seven and half million people fled across the border into Poland, the largest refugee migration in Europe since the Second World War.

Polish volunteers mobilised to help the displaced and welcome them into their homes, schools, and businesses and, over the next three months, an extraordinary 70% of Poles were involved in helping refugees, with their help and state aid amounting to almost 1% of Poland’s GDP. By the end of last year, Poland had spent about £7.4 billion on housing and health for Ukrainian refugees.

Most moved on to other countries, but 950,000 remain and Poland, like other European countries, is in the grip of a cost of living crisis, with soaring inflation and the prospect of gas and coal shortages. Facing its own financial pressures, the government recently ended payments to families who house refugees.

But, if Putin hopes Poles will grow weary of the economic cost of supporting their neighbours and the presence of hundreds of thousands of refugees, he will have, again, miscalculated.

Recent polls show 79% of Poles remain willing to take in Ukrainians and 77% are in favour of arming Ukraine against Russia. With more than three out of four Poles believing the war threatens Poland’s security, the fear is that, if Ukraine falls, Poland will be next on Putin’s hit list. The result has been an increase in support among Poles for the return of compulsory military service.

Poland shares a border with Belarus, the Russian ally and also with a 144-mile border with the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad. The former German city – surrounded by Poland and Lithuania – is Russia’s only ice-free port on the Baltic Sea and a major naval base.

In a report, the Polish Economic Institute said: “An important factor influencing the willingness to help is the awareness that we could become victims of violence, too. If it is easy for people to imagine developments in which they are the victims, the number and intensity of assistance will increase. We can assume that, in the case of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the following was undoubtedly important: the sense of the conflict’s proximity, compounded by the history of Poland’s relations with Russia.

“The fact the Poles were invaded by the Russians in the past may have made it much easier for them to put themselves in the place of the Ukrainians fighting for their freedom and statehood. A similar historical and political past may therefore make it easier for people to choose between helping and remaining passive.”

But the Polish Government clearly has concerns about the conflict escalating. Earlier this month Polish President Andrzej Duda cast doubt on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s request for Nato countries to send it advanced fighter jets, saying this was a “serious decision” and “not an easy one for us to take”.

An act of parliament has been passed giving Ukrainian refugees access to healthcare, education and the right to work. Many Ukrainian refugees are establishing themselves independently, with 10,200 firms set up in Poland between January and September.

While refugees arrived with skills, including accountancy and IT, some found they were initially only offered low-paid jobs.

Agnieszka Ciecwierz, CEO of Sigmund Poland, who helps Ukrainian women looking for work in the country, said: “Unfortunately, it is the general consensus among the Polish population that Ukrainian women mainly work in low-skilled jobs, such as supermarket cashiers or cleaners. We forget that often these are educated women who used to work in senior or specialised roles.”

Mariana Zlahodniuk, a Ukrainian marketing executive who has lived in Poland since 2012, has set up her own recruitment network for refugees. She said: “Generally speaking, the Polish people have been amazing. But in the food industry, for example, employers are exploiting Ukrainians by paying them less than the minimum wage.”

At the beginning of June, the Polish government stopped payments of 40 złoty (€8.50) per day for people hosting Ukrainian refugees.

Ciecwierz said: “The ‘help boom’ has now ended, not because the Polish people do not want to help but the amount of disposable income in a typical household is reduced.”

Poland has one of Europe’s highest inflation rates – 15.6% in July – in part caused by the war. The mass influx of Ukrainians has sent rents soaring with average prices for flats in Warsaw 24-32% higher than in 2021. But, despite the costs, Ciecwierz said:

“There are still money and food collections in grocery stores, shopping centres, and the internet, all across Poland”.

Poles and charity groups continue to make “aid runs” across the border to deliver food and clothing. Other examples of support include a hotel in the city of Walbrzych that gave refuge to 700 Ukrainians. It has retained 300 of them, saying they are “like family”.

In the newspaper Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, Maciej Duszczyk from Warsaw University Centre of Migration Research, summed up the view of many Poles. He said: “The tiredness with the topic of the war is clear, but the decrease in support for Ukraine is not as dramatic as one might expect.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe