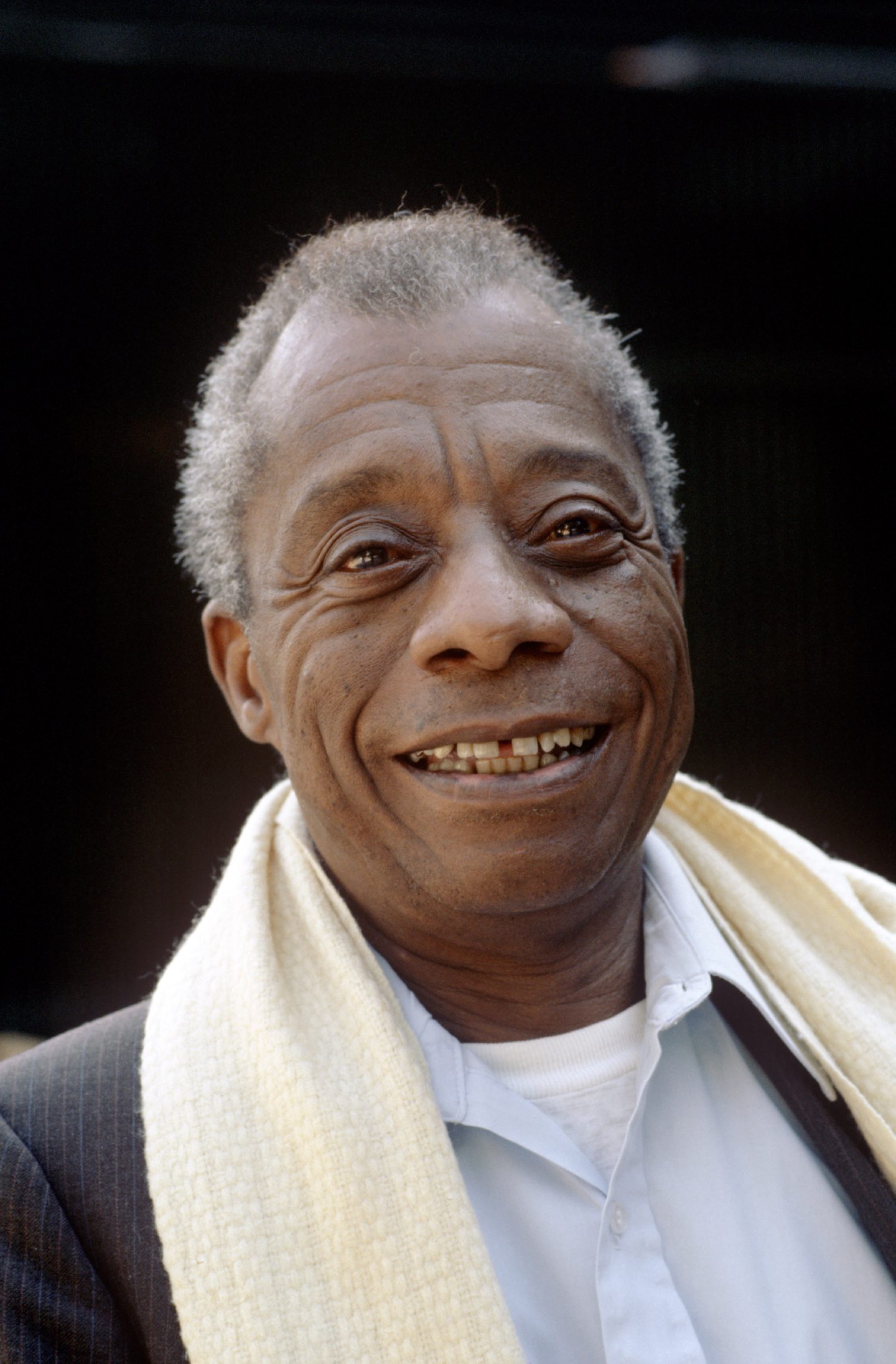

He was as eloquent as Martin Luther King, as outspoken as Malcolm X, a giant of the American civil rights movement. Yet long before his death at just 63, James Baldwin’s influence had faded, his writings forgotten.

More than 30 years later, the wheel has turned again and Baldwin was hailed as a totemic figure when the Black Lives Matter movement swept the world last year.

His writing was the basis for a Bafta-winning documentary, I Am Not Your Negro. One of his novels, If Beale Street Could Talk, was adapted into an Oscar-winning movie.

Author James Campbell first wrote to Baldwin as a fan, when still a student at Edinburgh University and, as his biography of the writer is republished for a new generation, is pleased but not surprised by the resurgence in interest.

“His work is simply too good to sit in the doldrums for too long,” said Campbell. “When his collected essays, The Price Of The Ticket, came out in 1985, it wasn’t reviewed in the New York Times. The same publication recently ran a major series on Baldwin over four weeks, so there has been a massive change.

“He was a writer of great quality, not a flash in the pan. His literary legacy is there to be learned from. Any writer who is trying to write elegantly, eloquently and entertainingly could hardly have a better model.

“These beautiful sentences and his powerful punctuation are a masterclass. There is also the humanitarian legacy – the level of morality in his writing, the opportunity to be a better person. He understood the world and his place in it. So his work had a moral dimension to it as well as a literary dimension, and that is quite the cocktail.

“If someone asked me who the most impressive person I’ve ever met was, I would have no hesitation in saying his name. He was electrifying in person.”

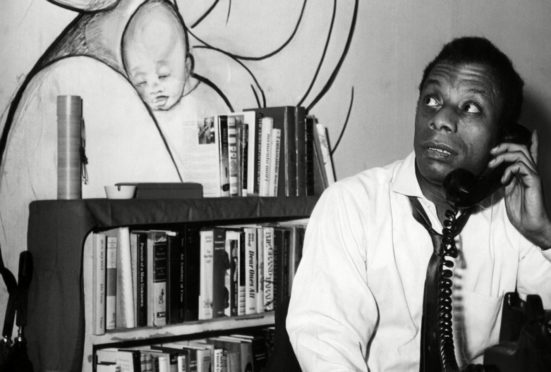

An eloquent and gregarious speaker and a hugely gifted, thought-provoking writer, at the height of his fame he was a TV producer’s dream and an editor’s delight. His groundbreaking essays and books dealt with issues such as masculinity, sexuality, race and class, and remain as powerful today as they did when first written.

But as his talent eroded and his focus became distracted, his literary voice faded and he struggled to find a publisher for his final novel.

Campbell’s biography of Baldwin, Talking At The Gates, was first published in 1991. He recalled: “When I first met him in 1981, his reputation was definitely in decline. He was almost forgotten in a way and he had difficulty getting The Evidence of Things Not Seen, his last book, published. It wasn’t very good and it’s an indication of how things were.

“After he became really famous, everyone wanted a piece of him and the telephone was ringing all the time. He was also compulsively sociable. His literary work suffered as a result.”

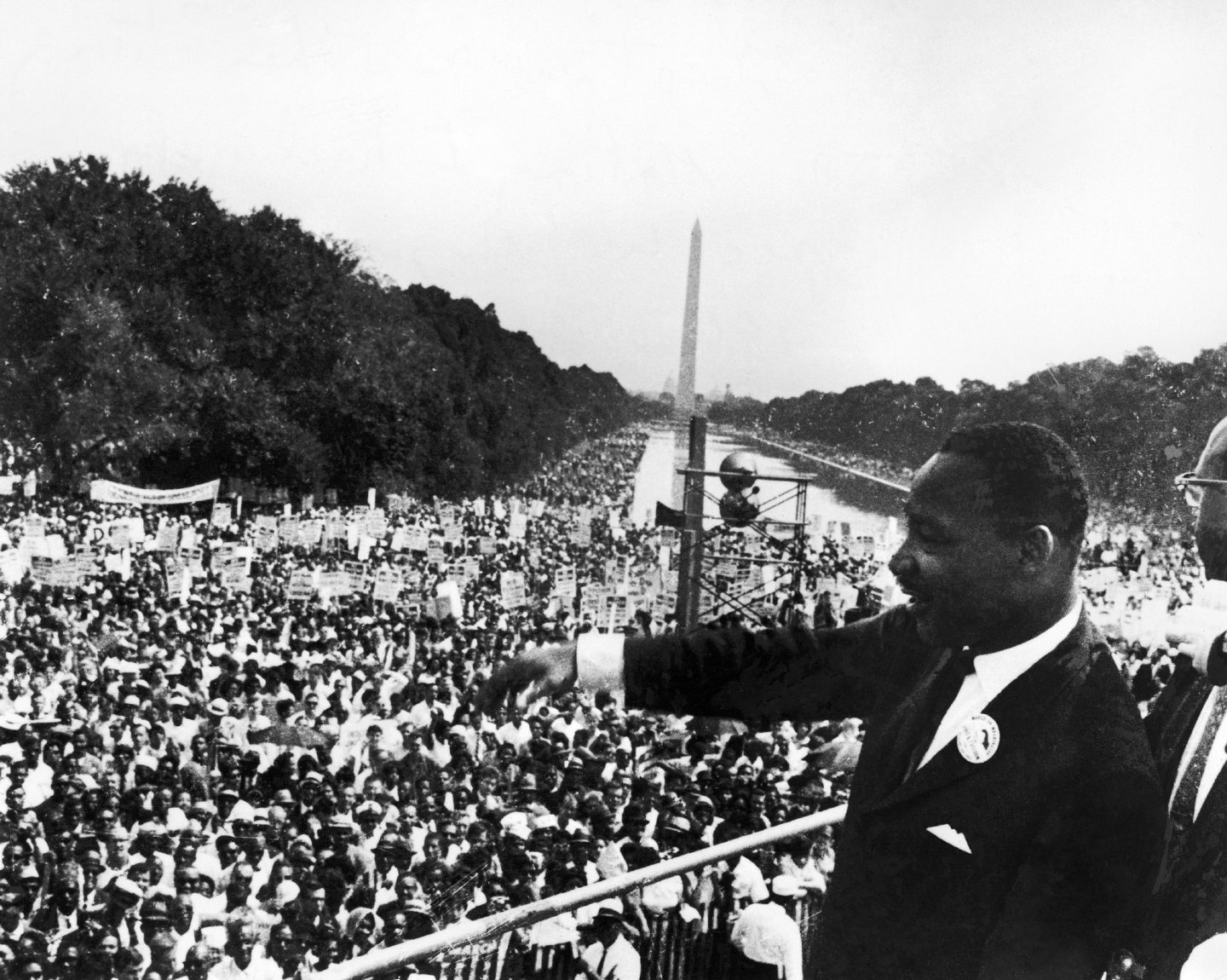

August 28, 1963

Baldwin was born into poverty in Harlem in 1924. He soon realised he had a natural gift for writing and his first article was published in 1947. Go Tell It On The Mountain, a novel, was released in 1953 and his first collection of essays, Notes of A Native Son, in 1955. He had already emigrated to France by that time, where he would spend much of the rest of his life, but he returned to the States during the civil rights movement.

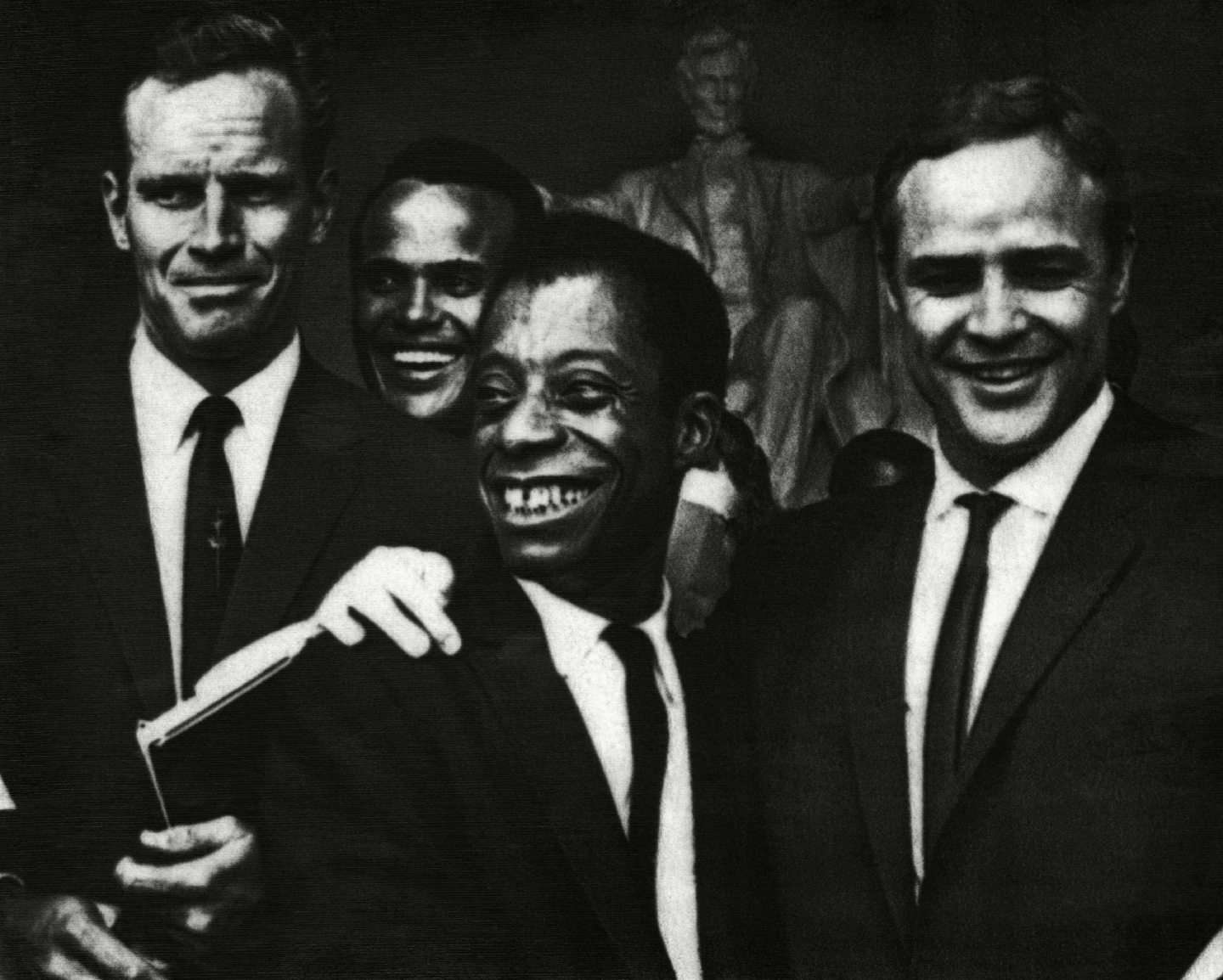

“He came back especially to take part in the March on Washington, but he was disappointed not to be among the speakers,” said Campbell. “Instead, he was part of a debate in a TV studio with Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando and Charlton Heston.

“A prominent figure like Martin Luther King and his movement were very image-conscious. They couldn’t afford to be associated with a prominently out gay man.

“They also felt Baldwin’s approach could become too emotional and they felt it was too risky. In Baldwin’s FBI files, which I was the first person to access, transcriptions of conversations where he was referred to as Martin Luther Queen and a comment from Stanley Levison, King’s lieutenant, that Baldwin could maybe lead a homosexual movement but not a civil rights movement, would have hurt Baldwin deeply had he known.

“He also tried to get in on the Black Panthers, but they rejected him.”

So while he stood alone, Baldwin certainly wasn’t speaking to himself.

“Not many writers do actually change things, but he was such an articulate spokesman – on screen, on the platform and on the page – that I think people who witnessed him speak and who read the likes of The Fire Next Time, Nobody Knows My Name and Notes Of A Native Son were affected by it,” said Campbell.

“I’ve noticed over the years there are very few people who came into contact with him for any meaningful amount of time who weren’t affected. I was affected. I was born and bred in Glasgow and hardly ever saw any black people at that time, yet his writing had a tremendous effect on me. It would not be too strong to say it changed my life in some ways.

“There were a lot of well-intentioned and good-natured white people who wanted to do something that would make a difference and they were, it’s not going too far to say, propelled into action by reading him on the page or watching him on the TV. He had such an impact.”

Campbell was a student of American literature at university in Edinburgh when he began reading The Fire Next Time, which was on his curriculum’s reading list. He was immediately struck by its tone. The wisdom and elegance of the writing, he says, was dazzling. He sought out everything he could by Baldwin and was so impressed that in 1979 he wrote to the author in France and asked him to give a talk at the university.

“He replied and said he would come, which gave me a terrible fright, because I had no idea what to do with him. The friend of the friend who had given me his address said he would probably be quite happy to sleep on my floor, but at the last minute he had to cancel.”

Several months later, Campbell invited Baldwin to write an article for the New Edinburgh Review. He was only able to offer £80, but Baldwin nonetheless agreed and a friendship was forged.

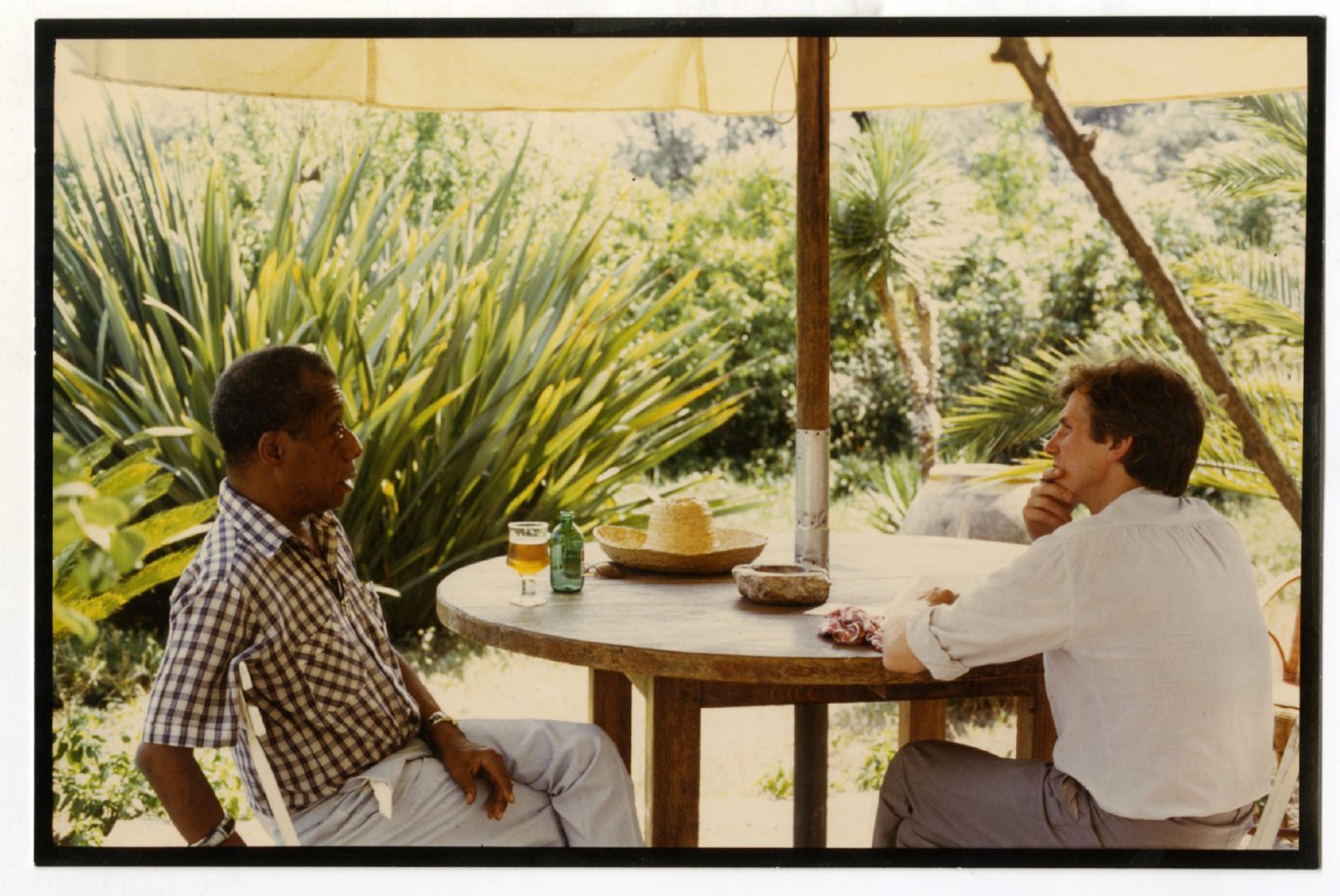

“Everything about it still counts as a major event in my life,” Campbell added. “I remember us walking up the hill in Saint-Paul de Vence, going to the pub, when he started singing the blues, and I remember thinking, my life is never going to get any better than this.

“But the issue there was he should have been working, rather than going for a drink. It’s a regret he was distracted too much. By socialising, by society.”

Talking At The Gates: A Life Of James Baldwin is published by Polygon on Thursday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Fanny Dubes

© Fanny Dubes © Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock © Everett/Shutterstock

© Everett/Shutterstock

© Probal Rashid/ZUMA Wire/Shutterstock

© Probal Rashid/ZUMA Wire/Shutterstock © Sten Rosenlund/Shutterstock

© Sten Rosenlund/Shutterstock