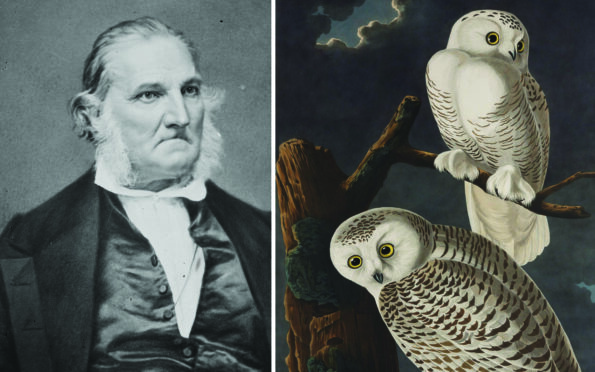

Monumental in size, overarching in ambition, and unsurpassed in influence, John James Audubon’s seminal The Birds Of America has become one of the world’s most revered books.

Creating a pioneering record of nearly 490 species, the four-volumes feature detailed hand-coloured illustrations, and was the first of its kind to document birds in life-size natural poses. Rare first editions will sell for $10 million at auction.

However, while the book by Audubon, regarded as one of the greatest ever wildlife artists, is renowned around the world, Scotland paved the way to publication after he crossed the Atlantic to Scotland in 1826.

An exhibition about the making of the book opens at the National Museum of Scotland next month and curator Mark Glancy explained how the author’s five months in Edinburgh proved pivotal.

He said: “People often think The Birds Of America would have been published in America, but Audubon was unable to find a printer there or even just get accepted by the scientific societies.

“So, he knew he had to move to Europe. He initially planned to pay a short visit to Edinburgh, just five days, because he was also desperate to meet Walter Scott. But once he was there, he met William H Lizars, who offered to then start engraving the prints. He also met with all the key people of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, and other naturalists, so that initial five days became five months – and he kept returning.”

The book

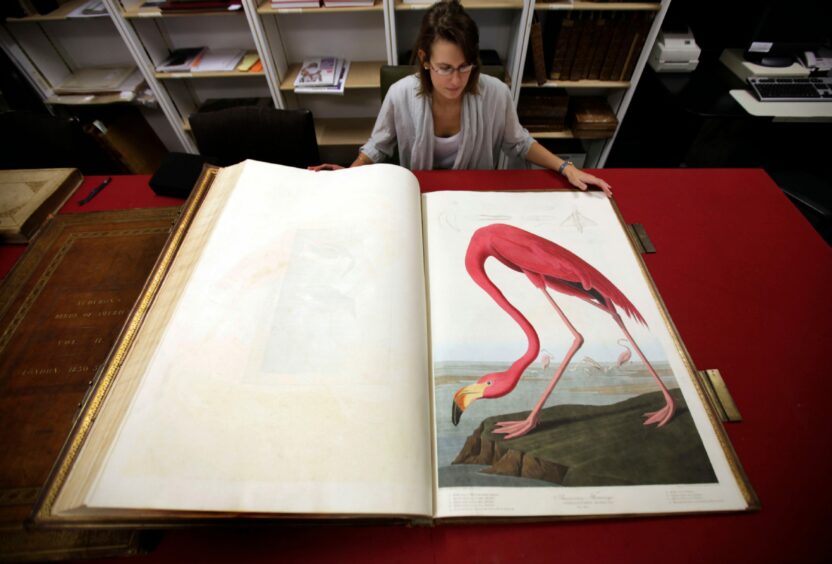

The four-volume The Birds Of America, like the one above at Sotheby’s, usually sell for $10m (£7m) when early editions go to auction. One set sold for $11.5m in 2010, a record for a printed book.

Experts believe 200 complete first-edition copies were produced over an 11-year period, from 1827 to 1838, with 120 known to be still in existence.

The monumental masterpiece includes 435 hand-coloured, life-size prints of 497 bird species, made from engraved copper plates based on Audubon’s original watercolours.

Where his contemporaries illustrated birds looking stiff and unnatural, Audubon was determined to depict his subjects – every bird species in North America, totalling more than 400 – in their full size. His more than 1,000 original paintings, vivid and full of colour, were carefully reproduced on hand-engraved plates, and printed on “double-elephant” paper, including the American Flamingo, Carolina Parakeet and Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

“He had to work with one of the largest paper sizes available,” continued Glancy. “The paper is one metre high and almost three-quarters of a metre wide – and even then he had to contort some of the birds to get them in that space.

“We have a number of rare bird books in the museum library, which we have on display in the new exhibition. They often featured very stiff poses, based on stuffed birds. What Audubon did was unique.”

Stephen Rutt, an Audubon fan and author of several non-fiction bird books, agrees the artist’s work was pioneering for its time, especially when compared to similar 19th-Century guidebooks.

He explained: “If you compare his work to British bird art of the time, it was really wooden with no expression and certainly not the colour that Audubon’s work had. His Carolina parakeet, for example, is so lifelike and vivid – it’s as good as seeing the species nowadays.

“We haven’t improved on his work for more than 100 years. Even now, modern field guides, which would be the direct descendant of his work, if not slightly more portable, are still a bit more static. There is an element of showing an ‘ideal bird’ and all of its features whereas, with Audubon’s, you get a really lifelike, animated, romanticised picture.

“How anyone got interested in bird watching in the 19th Century by looking at Bewick’s British Birds book [published in 1797] is beyond me.”

Published between 1827 and 1838, The Birds Of America was sold on a subscription basis and, costing £29,000 to publish, was only affordable to institutions, such as universities, and the wealthiest in society. Its publication as a series meant many subscribers dropped off over the nearly 12 years it took to finish, resulting in very few complete volumes surviving today. In 2018, a first edition was sold at auction for $9.65m.

The exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland will showcase 46 unbound prints, most of which have never been on display before, as well as a rare bound volume of the book and bird skin specimens.

As well as finding the first printers who could recreate his vision, Scotland also played an important role for Audubon – who was born in Saint-Domingue, in modern-day Haiti, and emigrated to America – as he was able to form relationships with peers, including famed naturalist William MacGillivray, who encouraged his work.

Barbara Mearns, co-author of The Bird Collectors, which explores the history and uses of bird skin collections, said: “Audubon got a lot of encouragement and recognition in Edinburgh. He had been treated quite critically in the States, so I think that kind of adulation probably shouldn’t be underestimated.

“MacGillivray was his most important link. Audubon wasn’t a scientist and English wasn’t his first language, so he wasn’t capable of writing the text for his work, so MacGillivray wrote a lot of it. It’s pretty bad, actually, that Audubon didn’t make him at least co-author, as he did the work and he had the scientific background. Although they did enjoy working together, and they were good friends.”

What’s more, the city’s museums held extensive bird specimens, which he used to bring his images to life.

She continued: “Although Audubon did collect birds in the States, certainly in the eastern half of the States, it’s really difficult to get all the species. The Scots had spent a lot of time in Canada, so in the Edinburgh museum there were specimens that have been collected by fur trappers and traders, and also people searching for the Northwest Passage. So, he made good use of the museum.

“People don’t realise the importance of these collections. If you’re an artist, what do you do, try to go out and shoot every single species in your country? Or do you use the skins that somebody else has collected? Edinburgh was certainly a good place for him to be.

“He borrowed things and he didn’t always take them back in great condition. He got a bit unpopular, as he was sticking wires into them. He was very single-minded, but he had to be with such a huge undertaking.”

Although recognised for his dedication to depicting scenes from nature in all their glory, Audubon is a controversial figure. He profited from the ownership of enslaved people and his scientific standing has also been disputed, as he made errors when identifying some birds.

He also sometimes shot and killed several of his feathered subjects before he found a perfect specimen. But, as Mearns explained, this was not unusual for birders of the time.

She said: “In the great scheme of things, I don’t think it mattered. The real threats to wildlife, particularly birds, came from the destruction of habitat, the huge pressure of hunting on certain species, and the millenary trade. It was the fashion at the end of the 1800s in the early-1900s for women to wear feathers in their hats, and sometimes hats were made entirely of wild bird feathers.

“Collecting skins was an absolutely essential phase in the development of ornithology. We wouldn’t have museums if people hadn’t collected birds. These collections, which many birders condemn, are also used by them. We would have no modern ornithology without these early collections. They were really important and they’re still used today.”

“Looking back now from our 21st-Century perspective, we have amazing optical equipment, which they didn’t – it was literally eyesight or gun,” said Rutt, whose latest book, The Eternal Season, was published in July. “His pursuit of perfection did involve killing, say, 10 examples of one species to get that perfect picture, which is sort of wince-inducing now with the weight of history.

“But it bothers me less than some examples, such as when the Great Auk was near extinction and there was a gold rush for its eggs and skins. That really hastened that species to extinction. Audubon probably didn’t have an active role in hastening the extinction of his subjects.”

Despite his failings in some areas, all three Audubon experts agree his influential legacy as an artist is deserving.

Rutt said: “There’s a good line in JA Baker’s The Peregrine, written in the 1960s, that reads, ‘No picture has the passionate living intensity of the real thing’. Audobon’s work is about as close as you can get.”

Audubon’s Birds Of America, National Museum of Scotland, runs from February 12 to May 8

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe