When Esther Woolfson started caring for fledglings that had fallen out of their nests, more and more people started bringing her injured or abandoned birds, and she became known as the “Bird Woman of Aberdeen”.

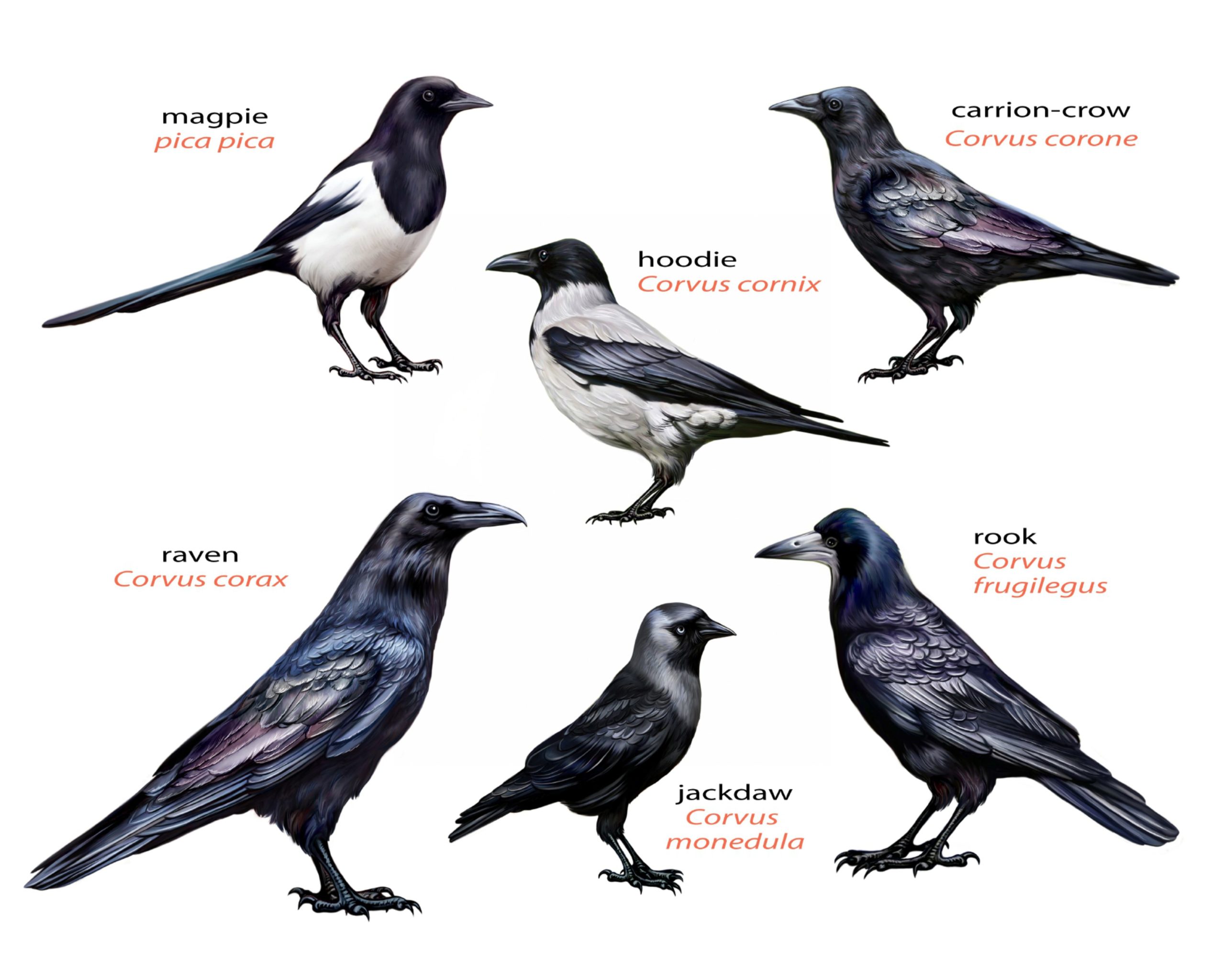

Over the years she’s looked after doves, canaries, and parrots, but she fell in love with corvids – the crow family – when her daughter rescued a baby rook and brought it home, calling it Chicken.

Amazed by its intelligence and quirky personality, Esther became fascinated by corvids and began reading up on the clever and sociable birds, which can recognise human faces and learn to talk.

“Chicken was a social being who knew her place in the family as a sibling to my two young daughters,” said Esther. “Corvids have incredible memories and as my daughters grew up and left home, Chicken would run to the door when they came to visit, cawing, with wings spread out to greet them.”

Her fondness for birds began when she moved to Aberdeen more than 30 years ago with her family and a neighbour asked her to take on some doves looking for a home. The coal shed was converted into a dovecot, then one of her daughters asked for a pet bird and Bardie the cockatiel came to live with them.

Word got around and people started bringing injured or unwanted birds. A pet-shop owner gave her a parrot that she couldn’t sell, and another parrot and canaries were off-loaded by a family leaving the city, as well as Max, a sweary starling.

“I didn’t know anything about rearing and caring for birds, so I bought a book about aviculture,” said Esther.

When her daughter brought home a fledgling rook that had fallen out of its nest, Esther successfully reared it to adulthood, and the family named her Chicken, short for Madame Chickeboumskaya. Spike, a baby magpie, followed, whose vocabulary stretched to shouting his name and cursing at people.

“Spike was hugely clever. I’d go into the kitchen where he’d be perched on top of the cupboards and call out his name, and he’d answer, ‘What?’” recalls Esther.

“He was really curious and would collect things. I’d hear him practising human intonation, copying my daughters, Rebecca and Hannah.”

Spike and Chicken became house birds, flying freely, hopping about, and perching on alarmed guests’ knees. Chicken laid eggs in the living room and tried to hatch them, and both birds stashed food under rugs, in holes they’d dug out of the walls, and pressed soggy titbits in Esther’s hands or hid them in the hem of her trousers as gifts.

They called to her at dawn and perched companionably on her knee in the evenings, teaching her more than she ever expected about birds and about human beings.

“Chicken, like all corvids, recognised herself in the mirror, something only humans, apes and elephants can do. Corvids have the intelligence of a seven-year-old child. I hate hearing people described as bird-brained as birds are clever, with memories and the ability to solve problems,” said Esther.

Chicken grew to the remarkable age of 32 and spent her elderly years reluctant to move from under a favourite chair, where she’d call out to Esther during thunderstorms for reassurance.

Esther went on to adopt her most recent corvid, a timid crow called Ziki, she rescued after he’d fallen – or been pushed – out of his nest.

“Something traumatic must have happened to him as he was silent for a long time and he’s always been nervous and shy,” she said.

Esther learnt more about the corvids who dominated her home and her obsession led to a writing career of books about them, including Corvus, A Life With Birds. Her latest book, Between Light And Storm, How We Live with Other Species, is about the relationships we have with animals.

“Having these remarkable birds in my home led me to think deeply about and research our attitude to animals, and why we dote on some animals and not others. We call ourselves a nation of animal lovers, but we only really like animals that are cute and fluffy.

“I’m not immune to cuteness myself, but in a time of devastating and irreversible species loss, it’s dangerous to focus on certain animals and not care about others that seem less attractive. Studies have evaluated the importance of a species’ appearance in determining its popularity or conservation status. A few charismatic, cute species receive most of the conservation funds and policy attention.

“Even the birds in our gardens are subject to our caprices, with a study showing we prefer songbirds such as robins and blackbirds to corvids, gulls, pigeons, and starlings. We consider the former attractive but the latter argumentative, competitive and noisy – natural behaviours of all wild birds.”

Esther is also concerned about the popularity of certain pet breeds, including “flat-faced” dogs such as pugs, French bulldogs, and Pekinese, which are prone to genetic breathing difficulties.

“Beginning with an already narrow gene pool, selective breeding has greatly increased the incidence of disease in these animals, many of whom, as a result of our choices, suffer from life-limiting or chronic, painful conditions,” she said.

“I was horrified to hear about people getting puppies during lockdown and then giving them to animal shelters when they grew up and the owners couldn’t cope. They would probably be better off getting a stuffed toy to talk to – it would fulfil the same role.”

Having thought long and hard about how we live with animals and concluded that we should treat them as equals, Esther now thinks that Ziki may be her last wild bird.

“Even before I learned about the physical make-up of his remarkable brain and the research done into the high cognitive function of magpies, I knew that Spike, my magpie, was clever.

“In observing everything he did and was, I knew he was my equal and more likely not less than me but more,” said Esther.

She looks back at the last time her daughters came to visit along with Rebecca’s parrot, a green-cheeked conure called Pocket, who said, “Thank you!” when given a dish of pomegranate seeds, and who flew over to greet Ziki with cries of “Hello, baby!” before dancing to her favourite music, the Darth Vader theme from Star Wars and Nights In White Satin by the Moody Blues.

“We discuss the delights and demerits of pet-keeping. The issues involved have become more complex in the years since we began with two white doves, a cockatiel, and a rook, and none of us can be sure that we would do again what we have done in keeping creatures.

“Although we try to reassure ourselves that we have done the best we can for them, and that they have always appeared happy, however a human can judge, that might not be good enough. We’ve borrowed their lives and the debt seems one beyond our paying back.

“We talk about what we could never have known without them, about the empathy of creatures, their learning, their fierce intelligence, their memory, affection, vulnerability, their unswerving faithfulness to who they are.

“I’m not more advanced than my crow. The belief that humans are not only exceptional but superior to every other species is being shown increasingly to be absurd. It has taken the imminent catastrophe of species loss and global warming to begin to demonstrate what we might have known all along: that we’re only part of a chain.”

Between Light And Storm: How We Live With Other Species by Esther Woolfson, Granta, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / Liliya Butenko

© Shutterstock / Liliya Butenko © Shutterstock / serkan mutan

© Shutterstock / serkan mutan © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM