Since Robert Burns compared his love to a ‘red, red rose’ it has become one of the most popular romantic poems.

As Valentine’s Day approaches, red roses are everywhere, offered in extravagant bouquets of a dozen or a dramatic single stem, and decorating sentimental cards to mark the occasion.

But while red roses are now the universal symbol of love and passion, thanks in part to this poem, Burns’ red rose was most likely pink, according to a botanical expert.

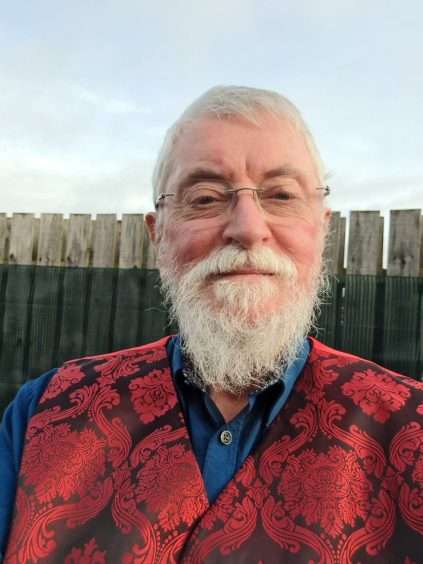

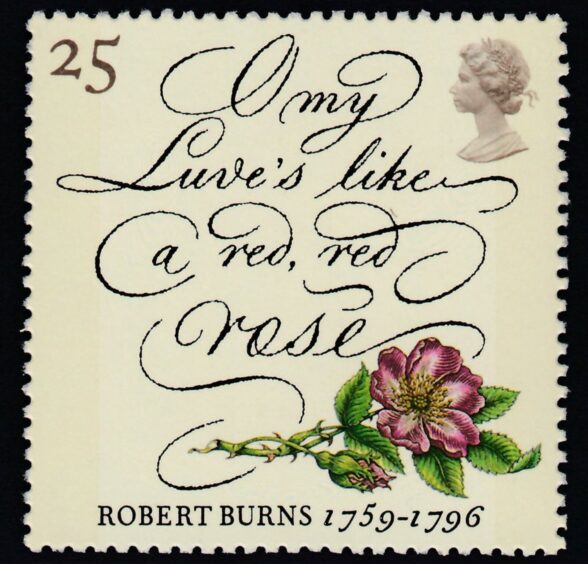

Colin Will, former chair of the Scottish Poetry Library, made the discovery when he was librarian at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and received an intriguing letter from a designer tasked with creating a set of commemorative Burns stamps.

“The designer wanted to be accurate and asked me about the exact species of rose the poet would have written about,” said Colin.

The question set him off on a fascinating search. After studying the Botanic Garden’s archives, he concluded the flower in A Red, Red Rose would have looked nothing like the popular image so familiar to the modern reader.

The famous poem

“The poem is very well known, especially in its song form, but there’s much more to it than most people realise,” Colin said.

His botanical knowledge and librarian’s research skills led him on a quest that took him all the way to China and back to a humble Ayrshire hedgerow.

“Many of today’s red rose cultivars are derived from Chinese rose species, but these original introductions were in 1798 at the earliest, and Burns’ 1794 song predates that. The only other two red roses in Britain at the time – the Damask Rose or Rosa damascene, and the French Rose or Rosa gallica – would have been found exclusively in the gardens of stately homes and would not have been known to the common man or woman.

“I asked myself, which native rose would an 18th-century west coast ploughman see all around him? Rosa canina, the dog rose, is the obvious answer.

“But it is pink, not red. Then I recalled that when they are in bud, the flowers are a purplish-red colour. I’m satisfied in my own mind that Burns was writing about the vivid red buds of the dog rose, ‘newly sprung in June’. When I read the poem, I don’t see the big blowsy blossoms of today’s suburban gardens – I see tightly-folded red velvet lips in an Ayrshire hedgerow.”

The rose is a common metaphor for love used by poets through the ages, and Colin cites Gavin Douglas, the 15th-century Scots Makar, who wrote about rosebuds breaking open to show ‘their vermeil lips are red’ – vermeil means purplish red.

“Red could have been a number of different shades at the time Burns was writing, including pink,” added Colin. “The word pink wasn’t used commonly to describe the colour, and it just doesn’t sound right in a poem.”

The geology

Colin is also a former librarian at the British Geological Survey and used his training in geology to make another fascinating discovery about the poem.

“The lines about all the seas going dry, and the rocks melting with the sun, mean that Burns must have had a grasp of ‘deep time’, an almost infinite length of time through which his love, and the world, would last.

“Geology as a science was new at the time Burns was writing, so this is a very modern poem. I believe he got his ideas either directly from James Hutton, the Berwickshire farmer known as the ‘father of modern geology’, or from Hutton’s friend Sir James Hall of Dunglass.

“In 1788, the two men discovered the famous Unconformity at Siccar Point in East Lothian, which proves deep time. It’s where an ocean going dry formed sandstone that was eroded and folded upright, then overlain after an unimaginable interval by another ocean, which also ran dry.

“Hutton’s conclusion that the earth was created over millennia – we know now 4.54 billion years rather than in 4,004BC as was thought at the time based on biblical study – was new and exciting when Burns was in Edinburgh. Hutton and Hall were among the distinguished men and women we know the poet met during his time in the city.

“Burns said A Red, Red Rose was a simple Scots folksong he picked up in the country, but I don’t believe that,” said Colin. “Surely there is an echo in this wonderful poem of Hutton’s words from The Theory of the Earth: ‘The result of our present enquiry is that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.’ I believe there is.”

In his final years, Robert Burns concentrated on traditional songs, including A Red, Red Rose, which he described as “simple and wild”, and is sung to the tune of a traditional song, Low Down in the Broom.

“With its intense feelings and strong metaphors, it’s no wonder this poem has remained a favourite,” said Colin.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe