More than 1,000 years ago, Vikings began to construct forts and farmsteads in Caithness and Sutherland, or Suder land – southern land – as they called it.

They quickly recognised that great tracts of wet boggy land were unsuitable for farming and described it using the Old Norse word “floi”, which means wet or marshy. It was from this Viking description that the tag Flow Country was derived.

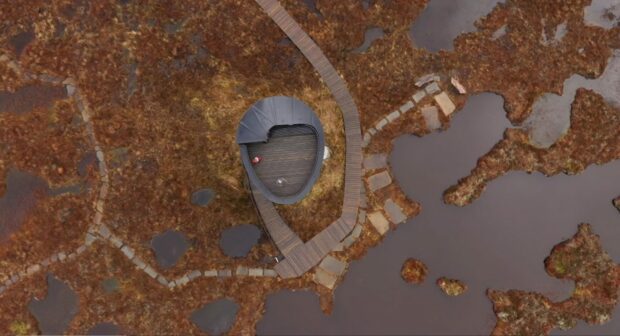

Today we know this enormous expanse of blanket bog, covering 4,000 square kilometres of Caithness and Sutherland, an area 16 times the size of Malta, is of worldwide importance, not only as a carbon store but as a globally rare and significant type of blanket bog, embracing a vibrant local ecosystem that includes insect-eating plants such as sundews and butterworts.

The exceptional habitat is home to a wide range of rare and endangered plant, bird and insect species that thrive in its interlinked bog pools and peatland vegetation, including populations of golden plover, dunlin, greenshank and black-throated divers.

Golden eagles, merlin, buzzards and hen harriers are common in the area. It is a magnet for ornithologists.

Scientists have calculated that the Flow Country, which, like a living fossil has remained largely undisturbed for the past 7,000 years, stores around 400 million tonnes of carbon – more than all the trees, forests and woodlands in the UK put together.

Hopes are now rising that this matchless Highland habitat, stretching from the A’Mhòine peninsula in the north to Strath Brora at its southernmost tip, could become a Unesco World Heritage Site, joining the likes of the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef as areas of outstanding importance to the common heritage of humankind.

As the world’s first peatland world heritage site it would be a major coup for Scotland.

Peatlands occur in 180 countries and cover 400 million hectares or 3% of the world’s surface but Scotland has the greatest coverage of peatland in Europe and therefore has a vitally important role to play in protecting and maintaining our global air conditioning system.

The Flow Country peatlands also act as a natural filtration system for the rivers and streams that run off and through it, providing cleaner water for wildlife and for the local population. Recognising the role of the Flow Country as one of the largest areas of blanket bog anywhere in the world, by awarding it Unesco World Heritage status, would therefore be of global significance.

The first step towards achieving this accolade was reached in 2020 when the Peatlands Partnership (now the Flow Country Partnership) submitted a technical evaluation to a panel of experts set up by the UK Government.

The panel gave its approval for the Flow Country to proceed to the next stage of the Unesco nomination process and it is now the UK’s official candidate for world heritage status.

A formal nomination package to Unesco is currently in preparation. The process has involved public consultation, with many recent meetings and events taking place this spring and summer.

There are great hopes about the benefits to Caithness and Sutherland that could arise from joining such a prestigious list. At the forefront are economic benefits ranging from jobs linked to eco-tourism and opportunities for businesses resulting from recognition of a World Heritage Site “brand”.

Obtaining World Heritage Site status may be an effective means to begin reversing long-term trends that have contributed to depopulation.

Of course, there are those who express caution about attracting more visitors to such an important area and, certainly, the attraction of the Flow Country to eco-tourists, wishing to stay longer and spend more money in this exceptional landscape, would be hugely increased.

However, the greater significance of the Flow Country to Scotland, the UK, and the world is its ongoing role in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss.

The bid will be submitted to Unesco by the UK Government at the end of this year and, following a site visit, a decision will be made in 2024. The bid is being supported by a broad coalition of partners including Highland Council, NatureScot, RSPB Scotland and Wildland Limited.

There are, inevitably, barriers, most linked to land management practices now seen as outdated. Huge conifer plantations, artificial drainage schemes, badly managed heather burning and even trampling by the red deer that roam the area, all need rethinking.

Misguided afforestation projects encouraged by UK Government tax breaks and grants in the 1960s, ’70s and early ’80s, saw forestry companies purchasing huge tracts of land in the Flow Country.

Damaging trenches were excavated to drain the land and swathes of alien pine and spruce trees were planted in dense formations, literally blocking out other forms of fauna and flora.

More than 60,000 hectares were planted with catastrophic consequences for the blanket boglands and their wildlife. A campaign to save the Flow Country began in 1985 and as public support grew, the government axed its tax breaks and grants and brought the whole afforestation scheme to a halt.

Soon, young, planted trees were being chopped down and allowed to rot, in the hope that over decades, peatlands would be re-established. Peatland restoration has since become an integral part of protecting the Flow Country, occasionally with help from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

If the Vikings of the 9th Century returned today, they would find much of the Flow Country familiar and fundamentally unchanged, with its vast expanse of blanket bog and interlinked pool systems offering a beautiful and vitally important landscape. It is surely worthy of Unesco World Heritage status and, surely, it will get it.

‘It would put the Flows on an even footing with the Grand Canyon. Well, it should be’

by Anne McAlpine, BBC Scotland journalist and newsreader who visited

the Flow Country for outdoors show Landward

Being an islander, cutting peat to use as fuel is something I’m very familiar with. But, as a kid growing up, you don’t give much thought to the peatland until you’re at the site again the following year doing the same thing again!

You don’t appreciate just how vast an area the Flow Country is until you see it for yourself. The scale of it is epic and of course it should be recognised globally, with it being one of the largest blanket bogs in the world. While it may not be so hospitable to us humans, it’s extremely important for our planet.

It’s home to a variety of significant plant life and particular species that adapt well to the harsh environment – cold, wet, acidic conditions that makes them important to biodiversity. Another thing that makes it significant is the carbon that is stored in the peat.

In the Flow Country there’s more carbon than in all the forests of Britain twice over. Not only that but it supports an amazing array of wildlife. It is a key site for climate change – making it one of the most important natural landscapes we have.

People understand much more now about the carbon capture and the special area that it is. If the Flows succeed with the bid, it would put them on an even footing with the likes of the Great Barrier Reef and the Grand Canyon – and why not?

There are many opportunities this could offer to the communities around about: a gateway to the Flows – for people to come and visit and appreciate it for what it is.

I don’t think anyone could ever be disappointed with the scenery around and about it.

It’s breathtaking. It truly is a wonderful part of the world.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM

© BBC Scotland/BBC Studios

© BBC Scotland/BBC Studios