Withdrawal of a crucial financial safety net could force carers in private homes to work when ill and put residents at greater risk of infection, campaigners warn.

Many staff in the private sector have no sick pay but, during the pandemic, the Social Care Staff Support Fund offered cover for carers with Covid or those self-isolating to curb the spread of illness. The fund was introduced in June 2020 but repeatedly extended amid fears over the impact of Covid among vulnerable care home residents.

The Scottish Government launched the fund, which guaranteed care staff £95.85 a week if ill or forced to isolate, saying it was essential “eligible social care workers do not face financial hardship when off ill or self-isolating due to coronavirus”.

The Scottish Government announced that the fund would end on March 31, 2023. However, trade union GMB Scotland says Covid remains a threat, particularly to the elderly and vulnerable, and carers should be given the financial support needed to protect them. The warning comes after a poll conducted for the union found Scotland’s care sector on the brink of collapse, with operators shutting homes amid an exodus of exhausted, underpaid staff.

Kirsty Nimmo, GMB Scotland’s lead organiser in private care, said the fund, which closed last month, should be reinstated until a comprehensive sick pay policy is agreed by private care providers.

She said: “Ministers were happy to applaud the commitment of care workers during the pandemic and they should not abandon them now. Covid is still here and the cost of living crisis is still here. The removal of this funding will undoubtedly mean our members losing badly-needed pay or risk the virus being spread in workplaces.

“Staff feeling unwell, possibly with Covid, will now have no option but to use annual leave, if they can, to avoid financial hardship or, it must be feared, go to work when they should not be there.”

Mounting dismay caused by low pay and poor conditions was exposed in the findings of a survey of carers published today but a report published last month found little of the £2.1 billion of UK Government emergency funding for care during the pandemic directly supported staff. The research, led by Warwick University, found profits in private care homes increased by £117 million during the first year of the pandemic, with shareholders’ dividends paid by 122 larger, for-profit care home firms rising by 11%.

The report, which suggested the finances of many private care firms were precarious before Covid, concludes: “The decision by government to end financial support for care home companies after the peak of the pandemic had passed has likely contributed to the current financial and operational difficulties experienced by the sector.”

HC-One, Britain’s biggest private operator, has announced it is offloading 71 homes across the UK, including several in Scotland, after reporting operating losses of £14m last year. Last week campaigners backed the GMB’s calls for the fund to be continued.

Alan Wightman, whose 88-year-old mum Helen passed away in May 2020 after catching the virus in Scoonie House in Leven, is the spokesman for the Scottish Covid Bereaved group. He said it was “only common sense” that the financial support for carers in the private sector should be reinstated without delay. “This support being withdrawn shows that carers aren’t valued in the way that they should be,” he said. “They do a vital job. Covid is still a concern in care homes for both vulnerable residents and staff. The government should bring back the financial support then introduce rules to ensure that employers are required to give these workers sick pay.”

Professor Anna Whittaker, an expert in behavioural medicine at the University of Stirling, said that catching or spreading Covid was still a real risk for care home staff and residents. “Current data suggests that Covid is still a considerable concern, particularly for those aged over 75 years and those with comorbidities related to their immune function that put them at increased risk,” she said.

Adam Stachura, head of policy and communications at Age Scotland, said: “It’s little wonder that care workers are leaving the profession for better wages where full sick pay is standard. The knock-on implications of this decision will be felt hard and instead of attracting more workers to the care sector will undoubtedly encourage staff to jump ship to professions where they are paid fairly and properly when they’re off sick.”

Social Care Minister Maree Todd said: “Pay and conditions play an important role in the wellbeing and retention of our social care workforce, and we are committed to improvement. Over the last couple of years we have increased the pay for social care workers by more than 14%.

“The Social Care Staff Support Fund available until March was to help care services and their staff cover the challenges of self-isolation and infection control arising from Covid-19. We are looking at how we can plan for, attract, train, employ and nurture the workforce, working with Cosla to deliver consistency of improved pay and conditions.”

‘Underpaid and overworked’… as workforce is on brink of collapse

Scotland’s care sector is on the brink of catastrophe as private operators shutter homes and despairing, burned-out staff throw in the towel, we can reveal today.

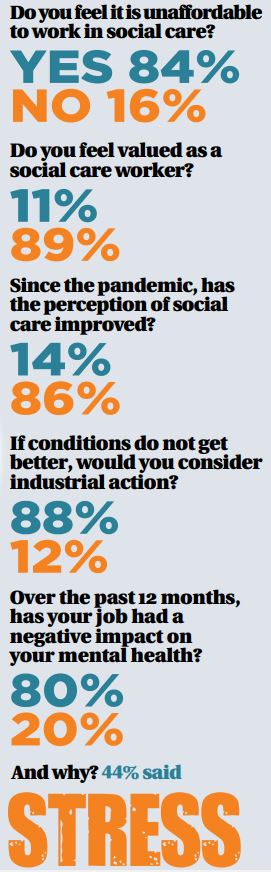

Concern for the care of some of the most vulnerable Scots is escalating amid ongoing uncertainty around Scottish Government plans for a new National Care Service and an exodus of underpaid, stressed-out staff. A survey conducted by leading trade union GMB Scotland today reveals the mounting dismay of many carers, with four in five admitting considering quitting in the last 12 months while 80% fear the stress of their job is damaging their health. Meanwhile, after government support during the pandemic ended, a series of private firms have announced homes will be sold or shut with, according to industry experts, many more considering closures.

The poll of carers has exposed the scale of the crisis of morale in the care sector with the vast majority of staff feeling unappreciated, underpaid and overworked. Rising levels of anxiety are blamed by 80% of staff who claim their job had damaged their mental health in the last year.

The poll of care workers found 82% had recently thought about leaving their job while 84% said pay-levels make it unaffordable to continue. Many staff said their job was taking an increasing physical and mental toll but said there was no sick pay and they could not afford to take time off if ill.

One staff member, who has worked in care for 20 years, said she had seen a dramatic decline in standards in recent years. She told the union: “Employers do not appreciate the demands, physically and emotionally and having no sick pay is a huge worry. In a 12-hour shift I get to sit down for a maximum of 50 minutes. I work in a fast-paced unit, giving care to people with a variety of needs. I am looking after the dying one minute and could be punched the next. I feel the challenges and stress of the job are now outweighing what was once a satisfying career.”

Another said: “Staff shortages are making the job so much more stressful. We are treated as expendable and uneducated. My workplace is trying to reduce costs by cutting the staffing levels to three carers for over 25 residents.”

One worker told how full-time staff were given part-time contracts to lower their statutory rights, adding: “Full-time workers are on 20-hour contracts, meaning less holiday pay, less sick pay, and having to work long days to make ends meet.”

A social care worker said: “Our workplace is good and our bosses couldn’t be nicer but £10.50 an hour is not enough to live off. I saw a job at the local rollerbowl as a dining assistant advertised recently for £12 an hour and that put things into perspective. We are at the sharp end of support work dealing with ex-prisoners who have a violent past and sex offenders too. We have to work weekends and some of us to overnights. We deserve a fair wage.”

GMB Scotland is campaigning for a £15 an hour minimum wage for care workers and said the staff survey confirms low wages are forcing skilled and committed staff to leave. Cara Stevenson, an organiser with the union, said the survey of staff had exposed the scale of the crisis of morale in the care sector driven by low pay and poor conditions. “These workers do one of the most critical jobs in any society. Their commitment to caring for some of Scotland’s most vulnerable people has been demonstrated again and again but their work is undervalued, under appreciated and underpaid.

“To avert a looming catastrophe in care, that needs to change and needs to change urgently.”

First Minister Humza Yousaf last month pushed back a vote on flagship care sector reforms with a vote on the creation of the National Care Service (NCS) until later in the year but the structure and costs of any new care blueprint remain unclear. Last week, Maree Todd, the minister in charge, told MSPs she was struggling “to get her head around” the proposals, adding: “This pause does give an opportunity to get a bit more detail, a bit more clarity.”

The delay comes after the NCS proposals – hailed by his predecessor Nicola Sturgeon as potentially the most significant achievement since creation of the NHS – were battered by criticism, with councils, care providers and staff unions warning the proposals risked a needless and damaging centralisation of management and demanded far more detail.

The NCS will involve new “care boards” directly accountable to ministers instead of being run by councils and health boards.

Yousaf told the STUC Congress last month: “I am confident that by taking that little bit more time, we will be able to reach a compromise – where staff remain locally employed, with local co-design and delivery of services, but within a national framework. I am determined to get the National Care Service absolutely right.”

With low pay and poor conditions, including the lack of sickness pay for many in the private sector, blamed for many carers leaving the profession and crippling staff shortages, critics have also questioned the timescale around Yousaf’s commitment to increase adult social care workers pay to £12 an hour.

He told MSPs that his government is “absolutely serious about improving pay, about improving terms and conditions for those who care for our most vulnerable.”

Beth’s story: It has been relentless, too much… It is only guilt that keeps a lot of us working

Beth McGowan, 60, has been a home carer with South Lanarkshire council for eight years and, before that, worked with a private care firm.

Here, she explains the mounting pressures and responsibilities of her job as four out of five carers reveal they have considered quitting in the last year.

It is no surprise that so many carers are thinking about walking away. We are just burnt out.

It is only guilt that keeps a lot of us working; guilt for the people we care for and guilt about what would happen to them if we didn’t.

That is our choice but it gets harder every year, the responsibilities get heavier, the stress gets worse.

People think we just go in, make a wee cup of tea and have a chat, but it is a hard, stressful job with an awful lot of responsibility.

There is an ageing population, a lot of dementia and families have changed. People are working harder and for longer. They don’t have as much time to look after elderly parents, for example, and we are stepping in to fill the gaps.

We now have to administer medicines, for example, double-checking names and dosages are exactly right. That could be 16 pills a day for some people and we are doing it in houses where the people might be confused, the TV might be on, the phone’s ringing and folk are coming and going.

You are not working on a production line, you’re working with people and have no idea what you are going into.

We could be doing 15 or 16 visits a day, travelling in all weathers. During the big snow a few years ago, the red alert, I was driving home at 10 at night, the only one the road, but if I wasn’t going to make sure they were OK, who would?

In the pandemic, long before there were any vaccines, we were out going house to house looking out for our people when most folk were safe at home.

You do feel a real sense of responsibility. It is hard mentally. It takes a toll and that is why so many people are thinking of leaving. It has been relentless, too much.

We are paid more in councils than in the private sector which is unfair but, across the board, there needs to be investment in staff, in pay, conditions and training.

Caring should be seen as a profession, not a just a job. It is predominantly women who work in care and that is one of the reasons our wages do not reflect our work. We have maybe not been as vocal as men about what we do and what it demands.

That is why people are talking about taking industrial action. It has never happened and no one wants it to happen, but somehow people need to understand what we do, how much depends on us and what would happen if we were not there.

If there is going to be a National Care Service, and if they want more people cared for at home and not in hospital, then there must be a levelling up of all staff not a levelling down.

That would turn a crisis into a catastrophe.

Staff must be valued more and their voices louder in shaping the future

By Louise Gilmour, GMB Scotland Secretary

Done well, it would, according to Nicola Sturgeon, be one of the Scottish Parliament’s greatest achievements, “like the National Health Service in the wake of the Second World War, a fitting legacy of the trauma of Covid.”

The first steps towards Scotland’s National Care Service (NCS), have, however, not been done well and it has joined other well-intentioned but difficult policies apparently consigned to the new first minister’s bottom drawer while he decides what to do next.

Humza Yousaf’s predecessor was speaking as she launched her government’s plans for care in September 2021 but, more than two years later, there is no NCS, no fitting legacy, and very little sign that anything will emerge any time soon from the protracted, contentious discussions around it.

The ambition of the proposals cannot be faulted and the reforms properly planned and funded could be transformative for those in need of care and those caring for them. No one would argue with such a grand plan but the devil is in the detail and, so far, the detail remains a mystery. So far, the NCS is a headline in search of a story.

The most serious problems facing our care service are inter-connected but clear. They should not be intractable but when, as revealed today, four in every five care workers are thinking of quitting, the need for change is evident and urgent.

The biggest fault-line is the pay and conditions of staff. Wages are far too low and it is no surprise so many feel undervalued. That means low morale, high turnover, staff shortages, a lack of continuity and a critical loss of experience, skills and commitment. The pressure, stress and responsibility piles on the remaining staff and the vicious cycle continues.

That is why pay must be a priority of any reform and why GMB Scotland has been campaigning so strongly for a £15 an hour minimum wage in social care. It is no more than a fair wage for such crucial work but Humza Yousaf’s recent promise of £12 an hour is another apparently stuck in his bottom drawer. Pay, however, is only part of the change demanded, albeit a crucial one.

Staff must be valued more and their voices must be louder when the decisions are being made on the future of care. Of course, we support Scotland’s vision of a world-class NCS. But we must build it from the ground up, shaped by a well-paid, fairly-treated, fully-trained workforce.

That must be more than a dream and more than a legacy. It must become a reality.

Choice for care staff: Hardship or spread Covid virus

Kirsty Nimmo of GMB Scotland Trade Union’s letter to the First Minister raising concern about the removal of crucial funding for care workers

Dear Mr Yousaf,

Congratulations on becoming First Minister of Scotland.

GMB Scotland Trade Union has written to you on many occasions about the Social Care Support Fund in your role as Cabinet Secretary for Health & Social Care. This fund has been a crucial lifeline for our members in the private care sector, who do not receive company sick pay when they are absent from work with Covid-related symptoms.

Since the Social Care Support Fund was established there have been several extensions but the Scottish Government announced that the fund would end on March 31, 2023, despite repeated requests by our trade union for it to continue.

Covid is still here and we are already receiving distressing messages from our members who are being informed that they will not receive normal pay if they are absent with Covid. Undoubtedly this will mean financial hardship for our members or a risk of the virus being spread in workplaces.

The financial safety net our members had has now been removed, many of our members now have no other option but to use annual leave for Covid absence to prevent facing financial hardship.

Please see attached a petition of support for the fund to be re-instated and I would be grateful if you would give this matter your consideration.

Yours sincerely,

Kirsty Nimmo

Lead Organiser, Private Care Sector GMB Scotland Trade Union

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Jane Barlow / PA

© Jane Barlow / PA © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley