The punters watch the wall-mounted screens as their bets come off or, more commonly, don’t and, on the wall, a Celtic star features in the most prominent promotional posters for the bookmakers.

It could be a betting shop in Scotland but it’s not. The poster of former Celtic captain Scott Brown, offering a 50% bonus for first bets, is enticing gamblers in Macharia Road in the Nairobi slum of Kawangware, one of the poorest in the capital, one of the poorest in the world.

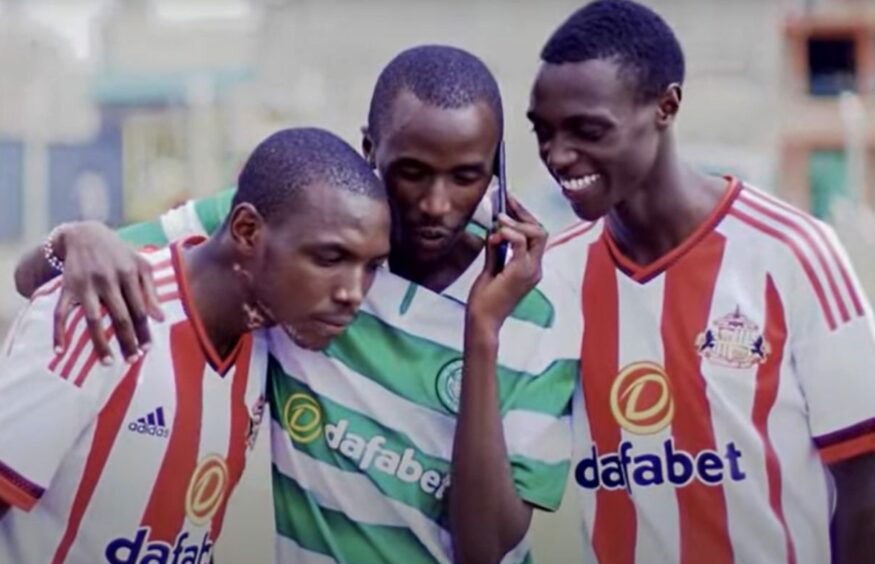

The shop belongs to international betting giant Dafabet and Brown’s presence on the walls is part of major drive by gambling firms into Africa that has seen British football teams used to push up sales. Men line up holding slips in their hands, waiting to place their bets on the next virtual horse race.

The drive into betting markets in Africa has raised concern with Dafabet, which set up a new African hub in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi in 2017, being only one of several gambling firms which have moved into the continent in recent years.

The past decade has seen the industry grow from strength to strength with foreign betting companies infiltrating the market not only in Kenya but across Sub-Saharan Africa. The industry in Kenya is third only to Nigeria and South Africa. Betting giants, Betway are now operational in 12 countries across the continent and has recently added the national South African rugby team as a partner and sponsor.

Bet365 also have a presence on the continent with most of their operations taking place online. William Hill and 888sport are among the various companies that operate in at least one African company.

Dafabet uses its sponsorship of Celtic and other top-flight European clubs to add the glamour of international football to its Kenyan operation.

Speaking in 2017 about the move into Kenya, Louis Watts, Dafabet’s retail and regional operations director, said: “We are looking to expand throughout the African continent and it was important that our first initiative was to establish a major presence in Kenya.”

But the rise of the gambling industry, which has seen betting shops open in some of Kenya’s poorest slums, has attracted criticism from some politicians and campaigners. Waithera Chege, an elected member of the Nairobi City County Assembly, said the industry’s rise was having a devastating effect. “The location of the betting shops should be checked,” she said. “The majority of the shops are located in informal settlements. This lures the poor and destitute. It is wrong as they spend all earnings, rent and even school fees, leading to depression and in some instances suicide.”

Chege wants a ban on gambling during the working day, from between 8am and 5pm. “My intention of capping the time limit of betting is to ensure that no person is betting during productive man-hours,” she said. “Betting, in my opinion, should only happen after regular working hours. We have developed legislation at both national and county government levels but this has not deterred the appetite for betting.”

The Kenyan betting market last year was £1.5 billion – a huge increase on just a few years ago.

“In order to deter people from betting the government has introduced two levels of taxation for betting,” she said. “The first targets the betting firms, which are taxed at 35% for earning. The second is a 20% tax on winnings targeting winners or beneficiaries from betting.”

Those taxes have not stopped the betting industry from earning an estimated £1.5bn last year, prompting Chege to propose the new betting hours. She is concerned about the use by betting firms of clubs such as Celtic to lend prestige to their businesses.

She said: “Teams like Glasgow Celtic should focus on corporate social responsibility to give back to Kenyans for the exploitation. It is not proper for companies to generate money in other countries and spend elsewhere.

“Often, betting money is raised through the exploitation of persons who are seeking quick money which often doesn’t materialise. The companies being sponsored by betting firms should find ways to give back to the countries that source their funds.”

Fellow Assembly member Anthony Kiragu has also spoken about his concerns. “I personally live and represent an area near Kawangware,” he said. “Having betting shops in the estates is a disaster whose effect will resound deep and wide. Betting companies in Kenya are all foreign, owned mostly by Chinese and Eastern European nationals. It’s sad that established football clubs accept sponsorship from such companies.

“Addiction to gambling is a serious problem in the country. Worse still, it is growing very fast as opportunities to bet are brought closer to the people. There are no official statistics on this problem and I would say the lack of that data is by design, not a coincidence. We are already glamorising gambling by posing stars to promote and insinuate that they are successful because of it.”

He added: “I wish that they insist on responsible business practices that protect the most vulnerable people.”

Earlier this year, the Gambling With Lives charity set up its Big Step campaign, which urged football to ban gambling adverts.

Co-chair of Gambling With Lives Liz Ritchie, who lost her son Jack to a gambling-related suicide, said: “Gambling companies are now stalking the African market, setting up betting shops and subsidising online gambling platforms. Research shows that this puts many people at risk of addiction, including children.

“Research also shows that suicide is highly correlated with gambling disorder so some people will die. Africa is already suffering from the global pandemic and this predatory targeting of the vulnerable will make suffering worse.” She added: “We would urge Celtic, and all clubs to cease any relationship with this operator.”

In the UK, betting firms may face a massive hit on their ability to advertise. Parliament is currently reviewing betting legislation with some proposals lined up to not only ban betting companies from obtaining shirt sponsors in sport, but to limit the amount of advertisements on television as well.

This will not only affect Celtic but will also see Rangers, which is supported financially by British-based 32Red, seek alternative sponsorship.

SNP Inverclyde MP Ronnie Cowan, who was a key part in a 2018 campaign that led the UK Government to reduce the spending limits on fixed-priced betting terminals from £100 to £2, criticised Dafabet for using the Kenyan market to make money.

He said: “It is a travesty that gambling companies can actively seek out market places with little or no regulation where they can exploit people to boost their profits. Many of these young people being targeted see gambling as a way to make fast money. This attitude encourages chasing losses and incurring debt to facilitate more gambling.

“As in the UK, it will be the most impoverished who are encouraged to gamble. Access will be made available day and night. No consideration is given to the welfare of those losing their incomes. This is driven by the appalling attitude that pervades from the sumptuous boardrooms and palatial offices of the greedy and conceited chiefs of these gambling firms.

“More must be done to reform the regulations so that vulnerable people are protected and we have a duty to hold companies to account when they are taking advantage of people and acting to their detriment.”

He added: We must understand that our actions in supporting such firms payrolls their enterprises in developing countries.”

Celtic declined to comment. Dafabet were approached for comment.

Tin shacks but a new betting shop: The shanty town where money is going to the bookies

In Kawangware, Nairobi, people pick their way through the market where goods are laid on the ground. Tinny radios play the latest Afrobeat hits. Mixed into the smells is the wretched waft of an open sewer.

The street is lined with shacks and mud huts, sometimes giving way to newer shops and stores made out of concrete. Dafabet’s shop is the newest building on the street, the concrete block painted in the company’s distinctive red, contrasting with the shacks topped with corrugated iron.

The exact size of Celtic’s deal with Dafabet has never been revealed but it has been described by the club as “Scottish football’s biggest ever front of shirt sponsorship deal”.

But the scene in Kawangware is a long way from the glamour of the Scottish club. A lack of regulation of the gambling market in Kenya means the industry has been able to thrive and their shop in Kawangware is encouraging gambling among people who can ill afford to lose.

Regulars place bets of between 50 and 1,000 Kenyan Shillings – about 30p to £7. Not huge sums, but the shop is in a part of the city where aid agencies say people earn just over £1 a day on average.

The increased presence of betting shops in such deprived areas has prompted concern.

Pauline Mwende, a social worker and community volunteer at the Kivuli Centre in the city, said: “Mostly it brings poverty, you find that maybe if it’s the men, all the income that they get, they take it to these betting centres instead of taking care of their families. So you’ll find in one household, there is no food but the complaint is they don’t take care of the family as they take all the money to bet.”

Asked whether there were any safeguards, Mwende said: “No, none. The government may shut down the company that facilitates betting but there are no rules or regulations on how to help those people who bet, who are addicted to betting. There is no help.”

In Kenya, gambling falls under the remit of the government’s Departmental Committee on Information, Communication and Innovation and a Betting Control and Licencing Board.

The regulations on have been unchanged since 1966 when the Betting, Lotteries and Gaming Act was introduced but in 2019 moves were made to replace it with a new act that would take into consideration online gambling and betting terminals inside shops.

It also plans to significantly increase the cost of obtaining a betting licence – currently around £20,000, to £200,000. And hopes to raise the minimum bet which gamblers are able to place as operators could previously accept any amount – prompting concern that poorer communities could bet anything they had.

In July, the Betting Control and Licencing Board introduced measures that would stop gambling ads targeting children.

Meanwhile, people like Job Ndombi, a customer of the bookies’ in Kawangware, look at betting as an escape from poverty. He told us: “When I win that’s when I get my income, but when I lose it goes just like that.”

Sports betting is impossible to ignore. Coverage of one recent English Premiership match shown in Kenya featured more than 50 adverts for betting firms such as Betway, SportyBet and Betika.

Benjamin Keter is a frequent customer both of Dafabet and other betting firms in Nairobi. He said he got into betting through ads. In 2020 he had lost his job due to the pandemic and now relies on the odd job and winnings from bookies to make a living.

Keter said: “In 2016, I had a job. I was younger but I used a lot of my money on betting and it changed my life. You use all your money and when you lose, you start trying to chase your money back, but it’s all gone.

“Sometimes it’s part of the enjoyment but sometimes when you don’t have a job or you don’t have anything to do, you try to get money through it. When you have a job, a good job and you’re making your daily bread, you try your luck. I don’t make it my job, but when I don’t have any work, I’m trying.”

“Right now I am addicted because I am always betting, yesterday, today and tomorrow. If I don’t get enough money I’ll use that small money that I have to look for my luck”.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© CHINE NOUVELLE/SIPA/Shutterstock

© CHINE NOUVELLE/SIPA/Shutterstock