It is more than 50 years since Charlotte Rampling burst on to the big screen but, she cheerfully admits, the work is still coming.

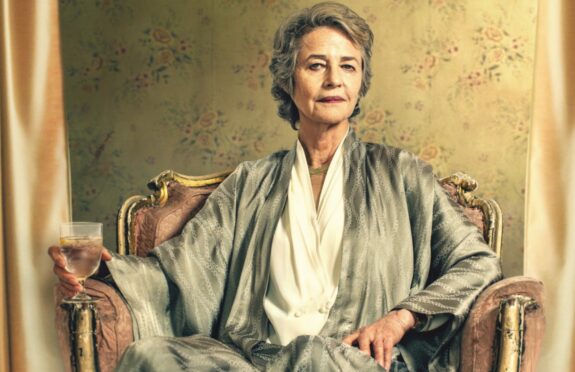

Now 78, she is as busy as ever but the actress, famous for her austere beauty and a trademark on-screen chilliness, refuses more movies than she accepts.

“Yes, I am busy,” she says, “but I’ve never been on a fast track. I have always worked on my terms and I have turned down a lot of stuff because it didn’t suit me, it didn’t suit the person that I was.”

The enforced idleness of lockdown was not easy for an actress who clearly thrives on work and had completed six films in the two years before the arrival of Covid.

“It happened so fast,” she recalls. “I’d just finished filming a film in New Zealand, and a week later I was locked in my flat in Paris.

“We heard rumours, then suddenly the president of France was on television saying, ‘Right, the restaurants all close at midnight, and you can only go out to do shopping.’ Remarkably, everyone just did it.”

“It was fine for a while,” she says, and then chuckles, “but the ‘while’ became quite long.”

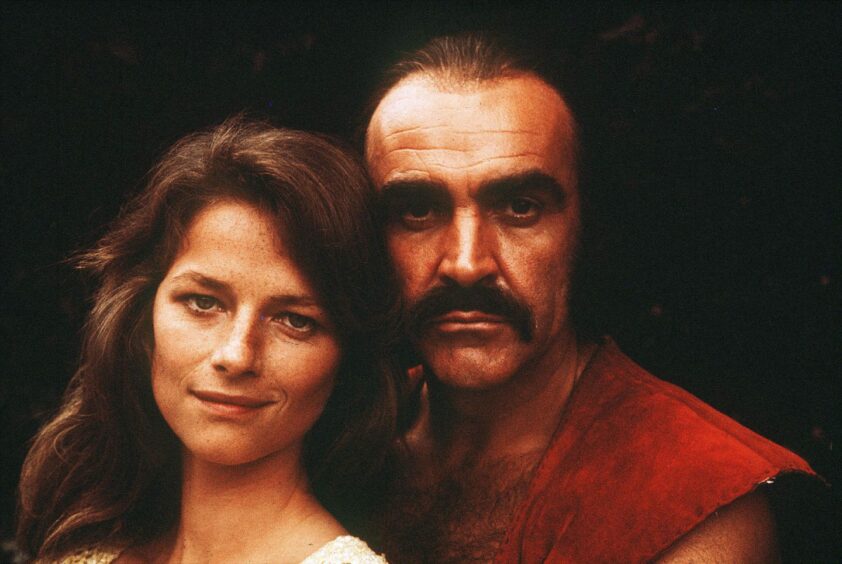

Her breakthrough roles made her a ’60s icon alongside the likes of Twiggy, Sean Connery, Marianne Faithfull and Michael Caine. Yet despite being a face of Swinging London, a grande dame in her adopted home of Paris, and now an international movie star, and now some of her fondest memories are of a film she made in Scotland, and the time she co-starred with Connery in the cult classic Zardoz.

The daughter of an army colonel, she was just 17 when she was spotted by a casting agent. Untrained as an actor, she became an immediate sensation after she appeared as Lynn Redgrave’s sexy but flinty flatmate in Georgy Girl.

As tough-nut Meredith she rebelled against motherhood and left meek but sweet Georgy to assume the role of bringing up Meredith’s child in the 1966 movie – an early example of Rampling playing the unthinkable and relishing every moment.

“Meredith was great, she was the start of women saying, ‘Just because you can impregnate us, we are not here just to do this.’ She was the beginning of feminism,” she says.

Yet although the part made her a star, Rampling was so convincingly cynical and self-assured in the role that, for a while, she struggled to get more work.

“I had great problems after Georgy Girl,” she admits. “Meredith was a hell of a handful and I was told later on that even film people were going – she must be terrible, we’re not going to take her. They should have known I was just acting. I wouldn’t behave like Meredith to my baby!”

One filmmaker who did see past the hard-bitten role was director John Irvin, who whisked her off to the Hebrides for a lyrical relationship movie called Strangers. “We shot everywhere, including aboard a boat touring the islands,” recalls the actress.

“It was the first time I saw the beauty of Scotland, and we made a lovely film for the BBC.”

A blossoming career as a UK-based movie star seemed assured but when she was 20, her beloved sister, Sarah, succumbed to post-natal depression and took her own life. Rampling went through a period of numbed grief, travelling widely to mend her broken spirit, including a stay at a Buddhist monastery at Eskdalemuir near Lockerbie which, she remembers, “helped me a lot. I was in real chaos. After the tragedy in my family, I thought I want to make movies that challenge audiences. I wanted to give meaning to what I was doing.”

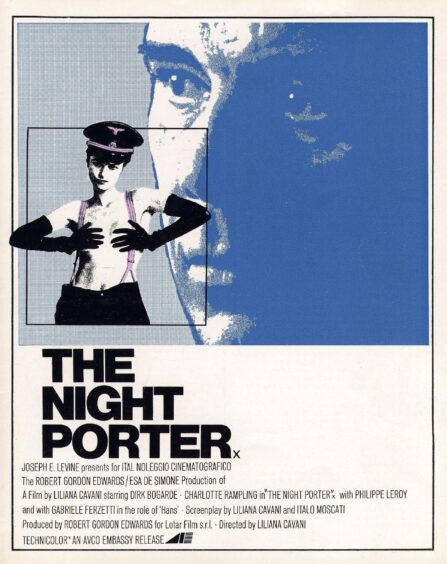

She packed up and left London for Italy and became a star in European art house movies like The Damned and The Night Porter. Since then she has worked all over the world, in everything from hit TV drama Broadchurch to the remake of big-screen sci-fi epic Dune.

It is one of the many contradictions of Rampling that while she is in person quite a self-contained and private figure, she often takes on roles that require extraordinary self-exposure. She has sought out complex female characters who grapple with loss, grief, betrayal, depression, and denial. Although the storylines do not overlap with her own life, many of the emotions and experiences do.

She was married twice: firstly for four years to New Zealand-born publicist Bryan Southcombe, with whom she has a son, Barnaby, then to French composer Jean-Michel Jarre until his affair ended their 20-year marriage.

A long and happy relationship to French journalist and businessman Jean-Noel Tassez ended in 2015 with his death from cancer, just as she was about to receive her first Oscar nomination for romantic drama 45 Years.

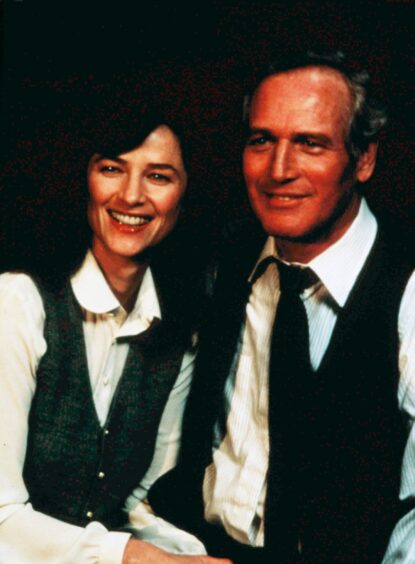

Hollywood was slow to appreciate Rampling’s unsettling Medusa gaze but eventually brought her fond memories of working with Paul Newman in The Verdict in 1982, with Woody Allen in Stardust Memories (1980), and with Connery in Zardoz in 1974. Despite the fact the Scot spent large swathes of the film wearing little more than a scarlet nappy, Charlotte says the former James Bond was “wildly attractive”, dividing his time between the film, playing golf, and flirting with the women on set.

“He ran after all of us,” she recalls, cheerfully. “I’m glad I wasn’t excluded. Years later, I saw Zardoz on French TV and, actually, I thought it was pretty good.”

At 78, she is one of the few ’60s stars still making waves in Hollywood. The filmmakers and actors with whom she then worked are either dead or long retired but Rampling continues to appear in challenging, provocative new films, living proof that good roles need not dry up at 40.

No one does chilliness and inner suffering on screen quite like her, and her character in her latest film, Juniper, is strikingly similar to others she has played recently – an imperious woman who at first seems remote, even unlikeable.

Her Juniper co-star, newcomer George Ferrier, was so nervous about working with the woman the French still call “La Legende” that he handwrote a formal letter of introduction confessing that he felt overwhelmed by her.

In Juniper, based on director Matthew Saville’s relationship with his fierce grandmother, Rampling plays Ruth, a former war photographer who is forced by old age and illness to retreat to New Zealand, where she battles with her grandson and reluctant carer.

“Like them or not, these women resemble me. Ruth is like me,” she says. “I would like to think in my youth that I could have been a war reporter, like her. And I recognise her heartbreak, her anger, and her difficulties – because I have known it too. I suppose the main difference is that I don’t drink when I’m working, and I’ve been working quite a bit. And I’d rather have wine than gin, and when I get a break, I’ll be having one, for sure.”

Five of the best

From dystopian sci-fi to animal attraction, here are five of Charlotte Rampling’s most memorable movie roles

ZARDOZ, 1974

A trippy vision of a decadent future featuring Sean Connery caught in a battle between brutal savages and bored immortal intellectuals. Rather than be driven to the set each day, Connery drove in his own car and paid rent to stay at the director’s house. “It was a hippie film,” says Rampling, “but they liked it in France.”

STARDUST MEMORIES, 1980

Director Woody Allen flew her back and forth between New York and Paris on Concorde as part of the deal for Rampling to play his girlfriend in the film.

MAX, MON AMOUR, 1986

She stars as society girl Margaret who falls in love with a chimp. “It was just like acting with Paul Newman, except the chimpanzee behaved a little differently.”

THE VERDICT, 1982

An alcoholic lawyer accepts a medical malpractice case and gradually recovers his sense of worth. Rampling is the mysterious barfly who threatens to undo all his good work. “Paul Newman was rather a shy man in real life but he was much easier to talk to when his wife Joanne Woodward was around, because he adored her.”

GEORGY GIRL, 1966

Her first big film role, playing Lynn Redgrave’s posh mean-girl flatmate Meredith in a landmark British comedy drama, with a famous theme tune by The Seekers.

Juniper is released in cinemas on Friday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe