UP to 51,000 children in Scotland are being raised by problem drinkers, a major health study warns.

Experts yesterday branded the plight of one in 18 Scots youngsters living with adults with alcohol problems a “hidden crisis.”

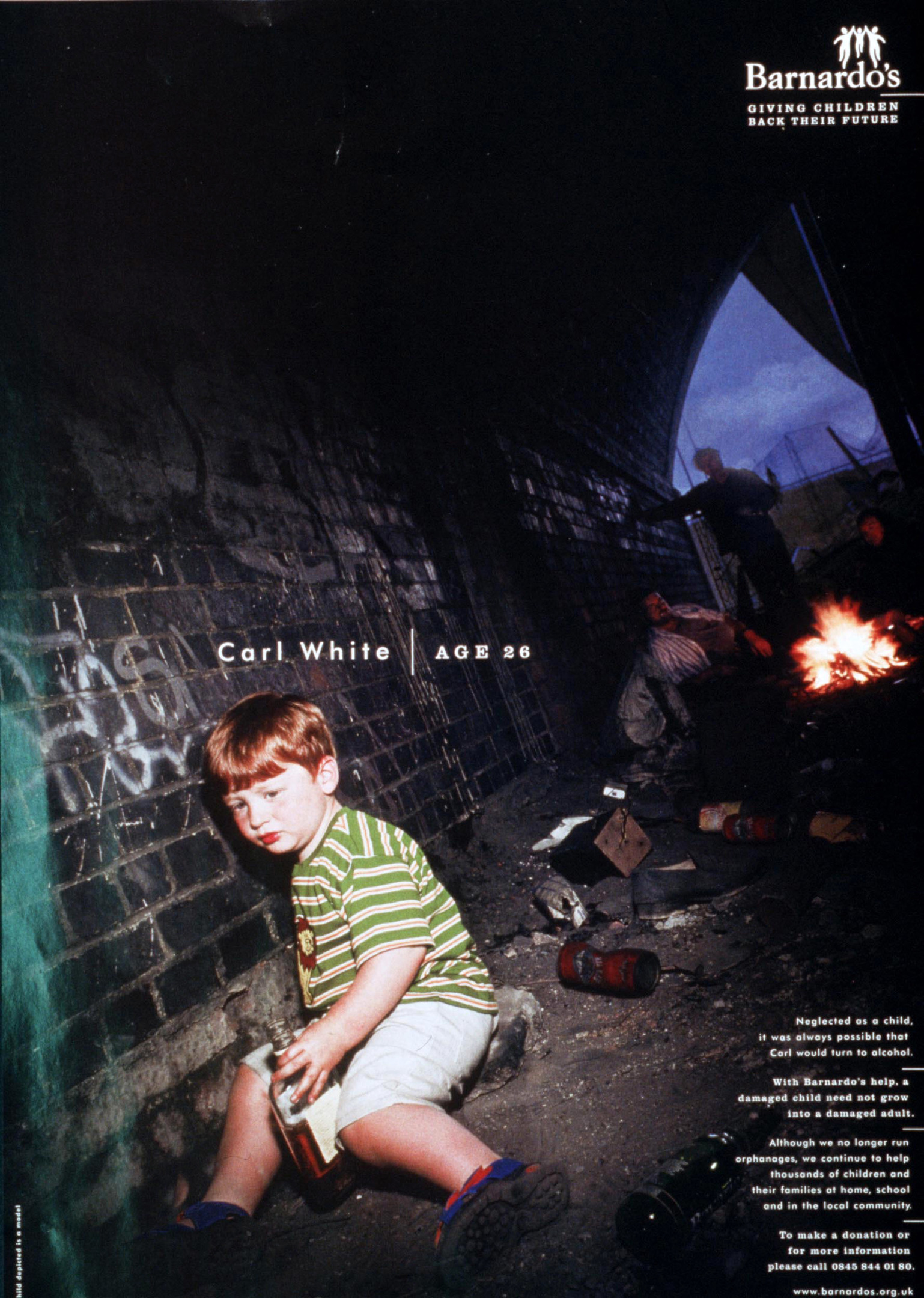

They said thousands of young lives are being blighted by neglect and stress linked to problem drinking.

Meanwhile, psychologists warned their futures could be shaped by their childhood trauma with some children of alcoholics growing up with their own issues around drink and addiction.

The figures revealed last week in the annual Scottish Health Survey lay bare the scale of Scotland’s drink problem.

- Between 30,000 and 51,000 children are being raised by problem drinkers.

- People in the most deprived parts of Scotland are more than three times as likely to die from excessive boozing than in the richer parts of the country.

- The NHS dealt with 130,000 alcohol-related problems last year – four times the rate in 1981.

- Falling alcohol prices now mean it is possible to breach the weekly safe drinking guidelines for just £3.

The number of children enduring the problem drinking of their parents has alarmed experts, who say greater awareness of the issue and better, more effective support is urgently needed.

Joy Barlow MBE, who co-authored the pioneering Hidden Harm report which highlighted the needs of children of problem drug users, said: “We just didn’t think of the impact of alcohol abuse on children and families.

“Essentially, society did not see what ought to be seen.

“I have been working in this area since 1985. Things have changed but there is still so much to do.

“The primary way this impacts children is neglect, the omission of things, even simple but important things such as emotional closeness.

“There is also physical neglect, unkempt children going to school or children being underfed because the parent’s dependency takes centre stage.

“You will often have a role reversal. From a very young age children are forced into things like budgeting, shopping and cooking.”

“The first recognition about hidden harms came though the illicit drug use strategy, but many of the issues facing the families of problem drug users are the same for problem alcohol users.

“We are only just beginning to catch up on the seriousness of this for the life chances of our young people.

“Schools have a role to play. Teachers see children as much as their parents and they can not only point young people towards help, but take practical steps in the situations, too.

“There is more in-situ help in schools with counsellors and the like but we need many more of them.”

The Scottish Health Survey, which covers nearly 6000 adults and children, was published last week. It claimed 36,000 to 51,000 children are living with a parent or guardian whose alcohol use is potentially problematic.

There are 915,617 youngsters under the age of 16 in Scotland, so up to one in 18 are looked after by an adult with a drink problem.

Justina Murray, chief executive of the Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs charity said: “We need wider recognition of the harms caused by alcohol to everyone in the family, along with appropriately funded services that will help young people feel comfortable to talk openly about what is going on at home to ensure their needs are fully met.”

The UK Supreme Court is this month expected to issue its verdict on the Scottish Government’s plans for minimum pricing.

Under the plans, a price of 50p per unit of alcohol would be set, taking a bottle of spirits to at least £14.

The controversial move has the support of the police and health groups but the Scotch Whisky Association and wine makers have challenged the move, passed by MSPs in 2012, all the way through the courts as they claim it is a breach of trade law.

The Scottish Health Survey says alcohol is now 60% more affordable in the UK than it was in 1980, making it possible to exceed the recommended drinking limits for a week for just £3.

In addition, the survey also shows there are more than 94,500 GP consultations and around 35,000 hospital stays each year for alcohol-related problem.

The rate of alcohol-related hospital stays has declined over the past eight years, but last year the rate was still four times higher than in 1981/82.

Liz Nolan, assistant director for leading children’s charity, Aberlour, said: “We work with children who have very low self-esteem and who struggle to form and maintain friendships.

“We see children taking on a caring role, sometimes looking after younger children in the family.

“Many have difficulty in keeping up with schooling because they are worried about what’s going on at home.

“We’d like to see more funding and better access to services for children, where they can benefit from one-to-one therapeutic support.”

Mary Glasgow, acting chief executive of the charity Children 1st, said living with alcoholic parents can have a huge impact on the life chances of Scots youngsters and increase the risk of them repeating their parents mistakes.

She explained: “For children living in families where there is substance misuse, life can be frightening, unpredictable and chaotic.

“Children may be very worried and anxious about what their parents might take if they go out and leave them.

“There is a growing understanding in Scotland of the impact of adverse childhood experiences can have on your long-term health – including substance misuse.

“By investing in increased support for families to prevent or reduce adversities and to help them recover, Children 1st believe Scotland will be able to halt the cycle of childhood trauma through different generations.”

She added: “Our staff work to build strong relationships with the whole family to ensure that parents are putting their child’s need for safety and security first.

“We offer practical help with things like routines and money advice and support parents to address the underlying challenges in their lives, to recover from their past, so that their child’s life becomes more stable, loving and nurturing.”

A national emergency

PEOPLE in Scotland’s poorest postcodes are three times as likely to die from alcohol abuse as those in the wealthiest areas.

The place with the highest percentage of deaths caused by alcohol was Orkney, where alcohol was to blame in 4% of all deaths last year.

There were 23 alcohol-related deaths for every 100,000 Scots last year.

In Aberdeenshire and East Dunbartonshire, two of the wealthiest council areas in Scotland, the rate was 11 deaths for every 100,000 Scots.

By contrast, Glasgow’s rate was 34 and Inverclyde’s was 38.

There is an average of 24 alcohol-related deaths every week in Scotland – a rate that has doubled in 40 years.

Official figures from the National Records of Scotland show the number of alcohol-related deaths in 1979 was 641, this steadily increased to a peak of 1546 in 2006, but then began to fall.

After a modern low of 1080 deaths in 2012 the rate has been steadily creeping up.

Public Health Minister Aileen Campbell said: “While progress has been made in tackling alcohol misuse, we want to go further.

“That’s why we need minimum unit pricing and our Framework for Action outlines more than 40 measures to reduce alcohol-related harm, including the quantity discount ban, a ban on irresponsible promotions as well as a lower drink drive limit and our nationwide alcohol brief intervention programme.

“I will be refreshing our Alcohol Strategy this year to further consider the additional actions and steps needed to tackle alcohol-related harm.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe