A taskforce has been launched to design and deliver the most radical reform of Scotland’s Children’s Hearings in 50 years, we can reveal.

A sheriff has been appointed to lead the group working to overhaul the hearings system to ensure the voices of young people and their families are heard more clearly.

The work has been ordered after the landmark Independent Care Review exposed a broken care system and is intended to secure significant change to hearings, where three-strong volunteer panels decide on issues around justice and the care and the protection of infants, children and young people.

The review warned Scotland’s care system is broken, with billions of pounds being squandered on a system that, it was warned, is not only failing some of Scotland’s most vulnerable children now but undermines their future.

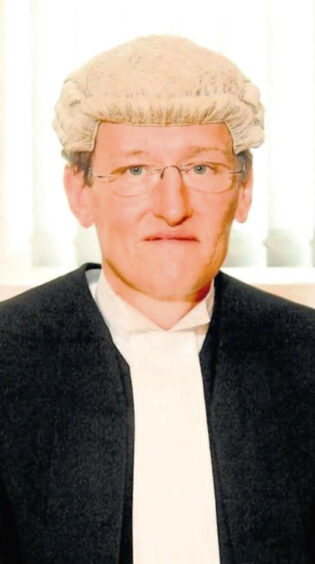

Retired sheriff David Mackie has now been appointed as the independent chair of The Hearings System Working Group and will spend the next year drafting a blueprint for change.

He told how 15 years on the criminal court benches in Alloa saw him despair over what he describes as the wasted potential of young people caught in the system and unable to free themselves from a cycle of crime and court.

He said: “It was deeply frustrating to see the same faces coming through my court every Monday morning after a weekend of them being involved in disorderly behaviour and low-level trouble which would earn them convictions and prison sentences, but didn’t change their behaviour.

“Taking an interest in finding out why they were doing what they were doing, looking behind what was being presented to us, proved to me that so many of these young people flourished when they were given not just a second chance, but a third, or fourth or fifth.

“If we do nothing, the loss of potential to all of us as a society is overwhelming.

“But if we offer support, I’ve seen it leading to them pursuing jobs and careers, allowing them to have a home, a family, and become contributing members of society.”

Children in care

Children in care are proportionately more likely to end up in the courts and prison system and proposals include keeping young people within the Children’s Hearing system until they are 18.

Mackie said: “I learned that people who have experienced trauma in their lives are more likely to respond differently to situations than others, sometimes with violence, or drink or drugs.

“One young man I spoke to regularly when he appeared like clockwork in my court every Monday suddenly disappeared after I’d asked him to think carefully about where he’d like to be in five years’ time. He stopped me in the street a couple of years later and told me with great pride that he’d taken a job and stuck with it, he’d settled down, got a house and was taking his child to Disneyland Paris.

“I fully admit that I walked away all choked up, especially when he thanked me for helping him make those changes in his life.

“That’s what I call success, and that’s what we need to see happening because right now I know from my own experience on the bench, children in care end up appearing disproportionately within the criminal justice system.”

Mackie is under no illusion that while young offenders will be dealt with under the system until they reach 18, there will be crimes committed by young people which demand rigorous sentencing.

He said: “Sometimes it really is appropriate to impose a sentence that has a high level of punishment and custody for specific cases which warrant that.

“They will still happen. If somebody does something dreadful, they won’t get away with it just because they are 18. Thankfully, however, those kind of cases tend to be few and far between.

“The vast majority of cases we tend to see in court from teenagers are low level offending, reflecting a childhood or background of abuse, trauma, absent fathers, addiction problems or witnessing domestic violence. Sadly Scotland has more than its fair share of that sort of thing, and its something that must be looked at too.

“What we want to see are children having happier lives. Knowing they are supported and people believe in them can have a markedly positive effect.”

Getting young people involved

Mackie will be aided by a number of young people who have experienced life in care, including good and bad decisions which shaped their whole lives. He said: “They have a huge contribution to make. I often found myself making decisions which were correct in law but I knew in my heart of hearts, would be absolutely devastating for the children involved.

“These often resulted in siblings being separated and children being taken from their homes and parents, even new born babies who were subject to emergency protection orders perhaps because a mother or both parents weren’t able to look after them perhaps because of addiction issues or mental health problems.

“The system meant that the point of intervention was literally at the point of birth.

“I often wondered if there was not a better way. It’s not a criticism of social workers doing their best but dealing with these issues in such a traumatic way may not have always have been the best thing for the child in the long run.”

Children coming out of Scotland’s care system are twice as likely to have health problems in later life or experience homelessness, and three times as likely to be unemployed by age 26. They are also half as likely to go to university. If they live in the poorest postcodes of Scotland, they are 20 times more likely to end up in care, two and half times more likely to be truanting or excluded from school, and twice as likely to be trying drugs by 16.

After publication of the Independent Care Review, chaired by Fiona Duncan, The Promise, an organisation working to secure the proposed reforms, was launched.

Writing in The Sunday Post today, Duncan says the vision of Lord Kilbrandon whose 1964 report provided the blueprint for the Children’s Hearings system remained sound but the reality was failing some children and their families.

She said change is needed and progress is being made: “There is unprecedented commitment from those that need to change first and most. There is cross-party support for change and no political impediment in the upcoming new parliament.”

Scottish Conservative social justice spokesman Miles Briggs said: “For years the focus has been on the process rather than the outcome, and when change is needed it moves at a snail’s pace.

“We’ve been spending billions of pounds on a system in crisis while people with good solutions have been ignored.

“Now we have real opportunity to make meaningful change, we need to move forward much more quickly before yet another generation is failed.”

Scottish Labour children’s spokesman Martin Whitfield said: “The children’s justice and care system is far too important for it to become a political football, so there is support from every party for these changes which are clearly long overdue.

“The roots of Scotland’s unique Children’s Hearing system has been incredibly valuable, and while there’s been such a lot of talking surrounding The Promise and what they plan to change, there’s a real danger here that we may lose some of those positive things the system already has.

“As a teacher who had contact with children in the care system, I found their experiences ranged from not understanding to not being listened to.

“Those fundamental things must be at the very heart of whatever happens next in Scotland.”

All my experience, the good and bad, could help those going into care behind me

– Working group member Beth Anne Logan

There are few Scots more qualified to deliver a clear-eyed assessment of Scotland’s failed care system than Beth Anne Logan. Thankfully, she’s been asked for one.

Now 23, she went into care at six weeks and is now the youngest board member of Children’s Hearing Scotland as well as a member of the working group planning landmark reform.

She said: “Sometimes, being in care made me angry. Sometimes it made me sad. Looking back I can see I was lost and in despair at times.

“But, I know I wouldn’t be here without the care system. We need to learn from the experiences of people like me to make things much better for people in future. I spent a lot of time being moved around like I was stuck in a pinball machine. I even had to move to England at one point to get the specialist help I needed in a low-security adolescent unit when I was 16 because there was nowhere in Scotland available to help with my mental health needs.”

Beth Anne, from Airdrie, has already played an active role in helping develop new standards within secure care based on her own experience and of others she had come into contact with.

And she intends applying those skills to help change the Children’s Hearing system: “I do feel the weight of responsibility for getting this right for others, but that is going to make me determined to take all the good things that happened an make sure none of the bad things are repeated.”

“I want to make sure that nobody else has to feel the way I sometimes felt.”

Ashley Cameron, 31, from Livingston, is a proud new mum to a baby girl of 10 months, as well as serving on The Promise Oversight Board. At the age of two she was placed in care because her mum had a heroin addiction and, through her experience in care until she was 18, Ashley suffered difficulties while being fostered. She has given evidence the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry to help ensure others don’t suffer similarly. “My experience was from being in children’s home and in foster care after a period of being looked after by a family member. I reckon I’m lucky I didn’t end up in a secure unit or becoming a young offender like many others,” she said.

She hailed the Kilbrandon Report’s vision of a Hearings System where children’s voices were clearly heard but said the reality in Scotland has failed to match that vision, adding: “We have a massive opportunity to make that right now.”

Meanwhile a young woman who has turned her life around after spiralling into underage drinking and violence when she was raped at 15 has spoken about her experience of being a teenage offender. The woman, now studying for a degree at Stirling University, said: “At 16 I should never have been in an adult court, but that’s what happened to me on my first offence and I was sent to jail.

“I was angry at everyone, especially myself and the more I bottled that up, the worse it got until I was drinking a month’s worth of alcohol in a weekend to blot out the pain.

“I eventually did get to university where I’m currently studying psychology and sport because I want to help other young people and make sure they don’t make the mistakes I made.”

The minister

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said the Scottish Government is fully committed to transforming the care system to ensure every child reaches their full potential.

He said some important reforms have already been made, adding: “In November, a national advocacy service was launched to reinforce the rights of children involved in the hearings system.

“By offering children and young people support to express their needs, we can help to ensure that, rightly, their voices are heard in decisions that affect their lives.

“Last month, legislation came into force to protect sibling relationships for children in care. This means that brothers and sisters will have new rights to appropriately participate – with support including advocacy services – in children’s hearings where contact with their siblings is being considered.

“Another crucial area of work is trauma training – recognising where people have been affected by psychological trauma and responding to that with compassion and care. We know this helps to prevent further harm and reduces barriers for people to access the services they need.

“People need to know that change is happening – but much work is still to be done and it will take a collective effort across society.”

The children’s reporter

Alistair Hogg, Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration’s head of practice and policy, said the drive to reform the hearings system is a “wonderful opportunity for a respectful, consensual approach to change”.

He said: “It also offers us the opportunity to tap into the extensive experience, skills and creativity of our own workforce, the panel community and other key partners in the Hearings System. Rights of children and young people will be at the heart of this redesign. Our Children’s Reporters, as gatekeepers in the system, already ensure that rights are at the centre of all our decision making. Acting in the best interests of children and young people is in the DNA of our staff.

“We look forward to working with The Promise and all our Hearings System partners, to create and implement a new vision for the Children’s Hearings System which will continue to protect our children and young people.”

The police

Assistant Chief Constable Gary Ritchie, who is responsible for Partnerships, Prevention and Community Wellbeing, said: “We are fully committed to supporting the fundamental needs of all our vulnerable communities, including the country’s care experienced young people.

“This pledge is at the core of our Corporate Parenting Plan, and aligned with our dedication to keeping The Promise for this group of children and young people. We look forward to working closely with the Children’s Hearing System Working Group and wider partners to contribute to shaping the future direction of what is a key protection measure.

“By working collaboratively with stakeholders, we can all maximise the support available for our young people when they need it most.”

OPINION: This is our moment to do better for our children. It is time to keep that promise

By Fiona Duncan, chair of The Promise

The history of the Children’s Hearings System is a uniquely Scottish story.

More than 50 years ago, since Lord Kilbrandon reported, our country has taken a distinctly welfare-based approach to children who need some state intervention in their lives.

The Kilbrandon Report established the principle of “needs not deeds” and determined that all children in need of some kind of compulsory state intervention, regardless of reason, were equally in need of care and protection.

The report was the basis of the Children’s Hearings System, which began operating in 1971 and is, in theory, the primary place where the voices of children – and their families – are heard about fundamental aspects of their lives, at critical decision points.

There have been some modernisations over the years, but it has functioned relatively unchanged for five decades. There’s always been a sense of national pride in the legacy of Kilbrandon, although in practice, not all children and families do enjoy the same treatment.

The Independent Care Review, which published the promise report in February 2020 and of which I was the chairwoman, spoke to thousands of children, families and those in the workforce – including panel members – about their experiences.

Many spoke about the hearings system and there were a range of experiences, positive and less so.

Children and young people talked about the frightening and intimidating correspondence that “compels” them to appear – language that is a Children’s Hearings System requirement.

Some children felt listened to by the panel, but how this often meant re-telling – and therefore re-living – painful stories.

Many were unhappy that panel meetings take place during school hours, and the stigma of being taken out of classes to attend.

Families reported panels lacked an understanding of the circumstances of their daily lives and the trauma they had experienced, as they rarely reflected, sociographically, the people before them.

Foster carers talked about being excluded from meetings. Panel members who are all volunteers, talked about how they didn’t always feel part of an organisation or listened to, with concerns not always followed up. Their responsibility is a heavy one – they are making decisions that can change lives, yet their relationship with Children’s Hearings Scotland is complex and provides little structure for accountability. The workforce talked of the bureaucracy and time it took to produce the paperwork the panel needed, and how the increase in families introducing lawyers to hearings was creating new challenges.

Scotland must do better – and it can.

There is rightly significant support for the underlying principles that underpin the hearings system, from children and families to panel members.

The Promise report outlined what the Care Review heard must change and The Promise Scotland, the independent body tasked with driving that change, has laid out how it can be done.

There is unprecedented commitment from those that need to change first and most. There is cross-party support for change.

This working group, charged with redesigning the hearings system to place children and families with lived experience at its heart, is important for what it will do and important for what it signifies.

This is Scotland’s moment to do better for its children and families.

This is what it means to #KeepThePromise.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley

© PA

© PA