These are dangerous times for statues. Last year saw an infectious wave of protest that led to the vandalism, beheading and toppling of controversial effigies around the world.

More than one Christopher Columbus came a cropper at the hands of US indigenous rights activists. King Leopold II found himself spray-painted blood red and dumped in a skip as 80,000 Belgians signed a petition to remove all vestiges of the colonial monster from the country. In Bristol, slave trader Edward Colston was suddenly sleeping with

the fishes.

This, then, could be seen as an inauspicious moment to propose erecting rather than ejecting a statue, particularly if the subject is a wealthy white male.

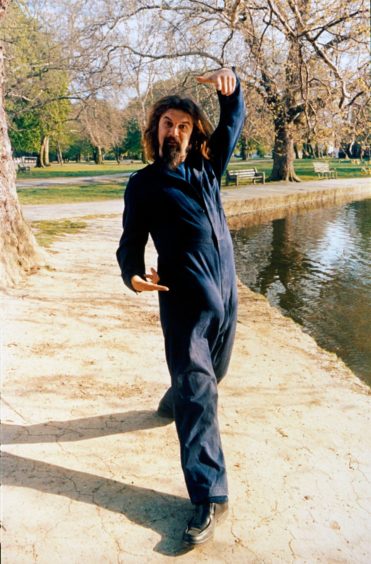

But if any Scot is worth it, the Big Yin is. Billy Connolly, that vibrant, fearless missile of working-class wit, that sweary, banjo-wielding shipyard bard, is now, unthinkably, 78-years-old and ambling into his later years. Since 2013 he has been living with Parkinson’s disease. In a moving documentary at Christmas he announced he was lowering the curtain on a 50-year career that has taken him from the Govan shipyards to the heights of Hollywood.

CAMPAIGN: A statue for Billy Connolly – celebrity fans lead calls for a tribute to the Big Yin

Connolly is facing the inevitable decline that Parkinson’s will bring with typical courage and forthrightness. “It’s got me, it will get me and it will end me, but that’s OK with me,” he says. “I achieved everything I wanted, played everywhere I wanted to… I did it all.”

He did it all, and in the process he threaded himself into our national DNA. It is hard to imagine Scotland without Connolly, or being Scottish without a connoisseur’s appreciation of his work. Those extraordinary, rambling monologues and sudden, mad, diversions (did he know where he was going? Of course he did).

Those drawn-out Glaswegian vowels: ‘It’s troooOOOOooooo’. The banana boots and, later, the eye-watering shirts and suits. The constant sweeping back of the shamanic hair. The puckish goatee.

We Scots have understood and appreciated every moment, every reference and allusion, the melodic beauty of the swearing, the slow build to the devastating denouement, where it was all coming from and the genius with which it was all deployed. We laughed and laughed and laughed. And as Billy took Scottishness to the world, and won, we beamed.

There are so many great, shared moments, that one Scot can recall to another using the briefest of shorthand. The Crucifixion. The incontinence pants – “cares not a jot… he’s seven gallons down each leg”. The body in the midden – “I need somewhere to park my bike”.

The one-liners: “never trust a man who, when left alone in a room with a tea cosy, doesn’t try it on”; “my definition of an intellectual is someone who can listen to the William Tell Overture without thinking of the Lone Ranger”; “before you judge a man, walk a mile in his shoes. After that who cares? He’s a mile away and you’ve got his shoes”; “Scotland has the only football team in the world that does a lap

of disgrace.”

And, in the end, our relationship with Connolly is as much about our own lives and memories as it is about him. Families listened to his records or watched his shows together. Mothers tutted at the bad language, but with a giveaway twinkle in their eye. Fathers passing on their worn cassettes, changing lives in the process. Grandfathers insisted they had known at least five guys in the yards or down the mines that were even funnier (they really didn’t).

Billy Connolly unites us in a way that little else does, especially in these fraught and often combative times. So why not raise a statue to the great man while he’s still here to enjoy it?

In doing so, we would be paying tribute not just to the Big Yin, but to the very best of Scotland, and of ourselves.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock © Jamie Simpson/Herald & Times

© Jamie Simpson/Herald & Times