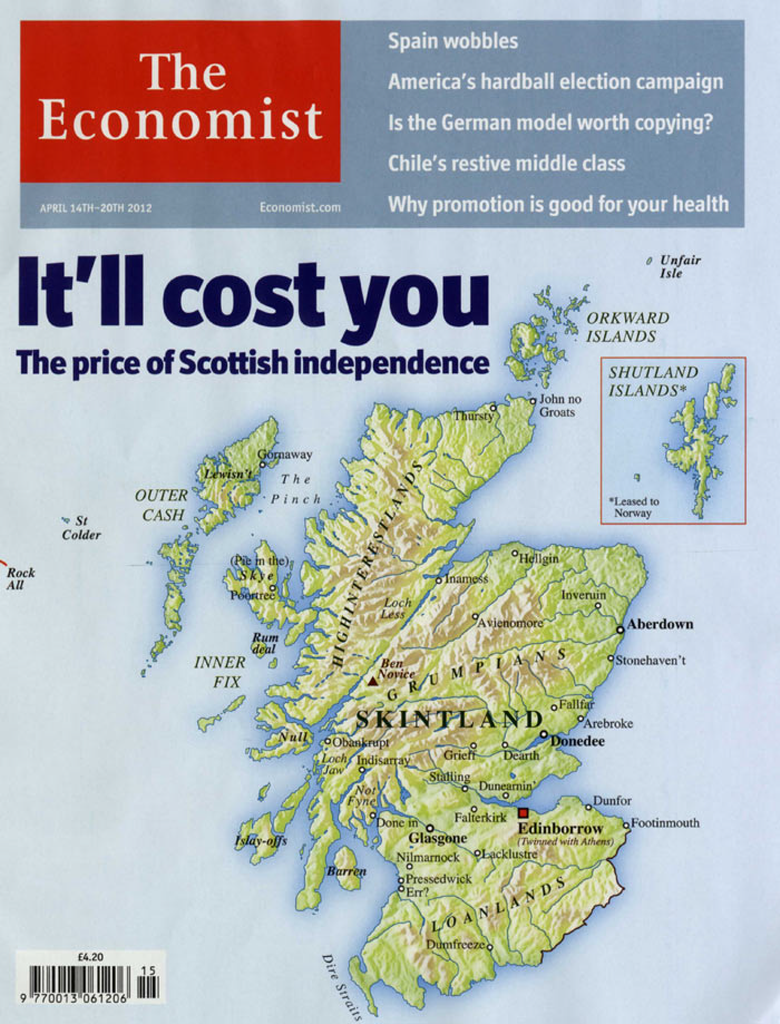

BACK in 2012, the globally-influential Economist magazine published a front page that quickly became notorious in Scottish Nationalist circles.

The cover image was a map of Scotland with the word SKINTLAND written across it. The nation’s cities were similarly renamed: Edinborrow, Glasgone, Aberdown, Donedee, and so on. Just in case the not-so-subtle message was missed, a large accompanying headline warned: “It’ll cost you – the price of Scottish independence.”

The message this sent around the world was hardly one to spark tartan pride or a flurry of international investment. Times change. This week’s edition returns to the economics of separation and strikes a considerably more measured tone. The SNP is now taking “an altogether more sensible approach” to its forecasts and predictions, says The Economist.

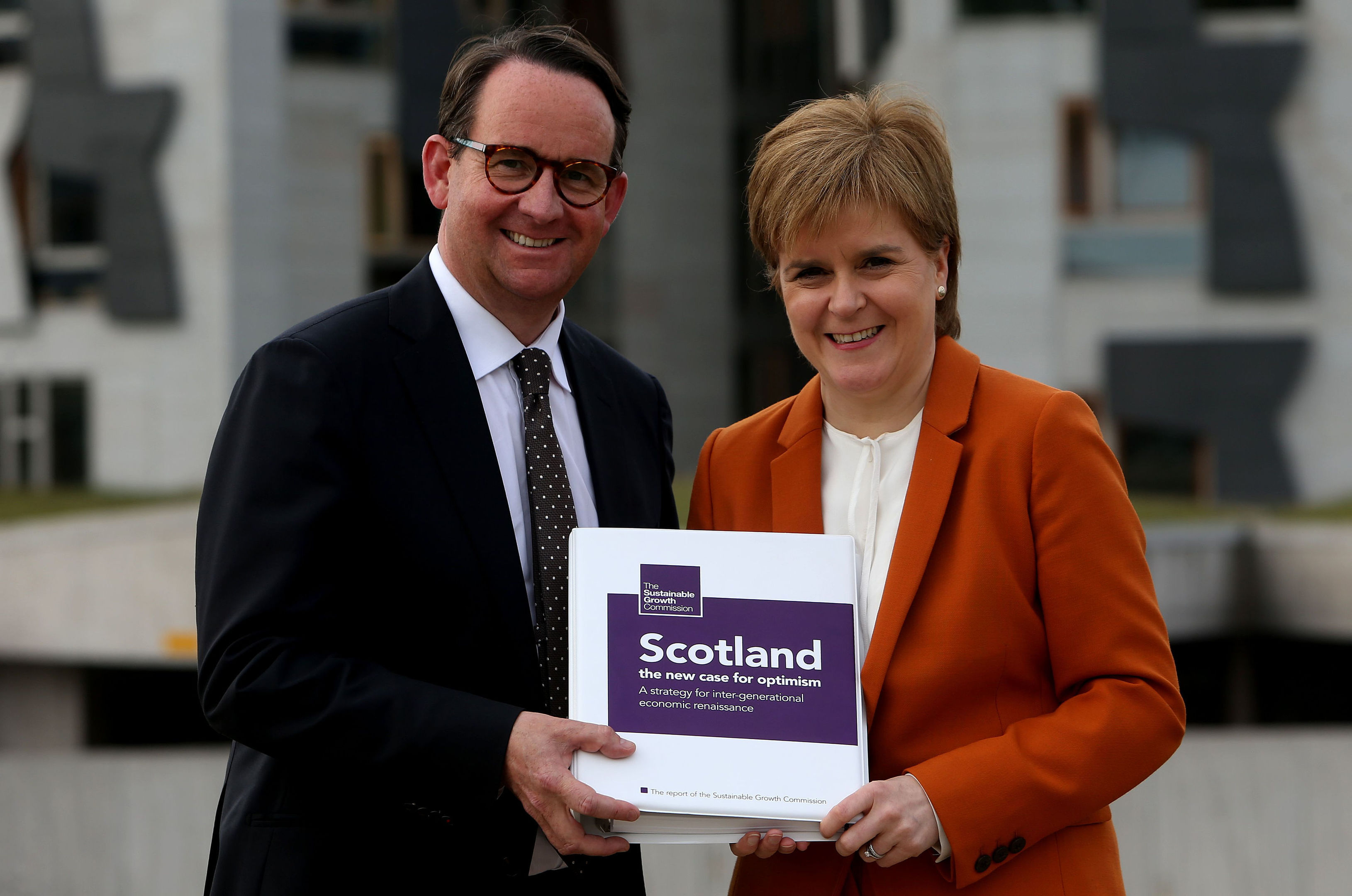

Inspiration for this reappraisal is the recently-published report by the party’s Growth Commission, which dramatically rewrites the economic case for independence advanced in the days of Alex Salmond.

In place of the old refusal to acknowledge the challenging circumstances that even the birds in the trees know would face the new nation state there is a freshly-minted realism: there would be no oil bounty, there would be a multi-billion-pound share of the UK’s debt to be paid off, it would take time to bring the deficit under control.

The implication is clear, even if Nicola Sturgeon is reluctant to admit it and the report makes some rather heroic assumptions about economic growth to soften the blow: independence would hurt, at least for a while. In accepting changes of tone and fact, Sturgeon has not just broken with her predecessor, but crossed a Rubicon – there can be no going back now or ever to promises of unicorns and lemonade.

This “wiser” approach, says the Economist, could benefit the Nats in the unsettled Brexit era, when there is so much to play for and the old certainties are wobbling. “The nationalists have plenty more work to do to convince sceptical Scots of the economic benefits of independence, which would still represent a massive economic gamble,” it states. “But Brexit, which Scots voted against by 62% to 38%, has shaken things up…in the current climate, a small improvement in the economic case for independence could have a big impact”.

This analysis is borne out by new data from Sir John Curtice and the National Centre for Social Research, which shows 56% of Scottish Europhiles now support independence. And even though overall support for separation remains stuck around the 2014 45% mark, the number of Scots confident about the ultimate financial potential is rising.

In other respects, too, Sturgeon is having a better run than might be expected at this stage of the political cycle. After 11 years in government and despite the best efforts of her political opponents, her party remains stubbornly popular.

A YouGov poll published on Friday and timed to coincide with this weekend’s SNP spring conference made for startling reading. While Sturgeon’s personal popularity trails that of her main rival Ruth Davidson, the more important numbers around electoral performance are still sound.

Voting intentions for Holyrood put the Nats at 41%, an increase of three points, and for Westminster they are at 40%, a rise of four points. While this would see Sturgeon lose her current pro-independence majority (which includes the Greens) at Holyrood, she would be comfortably returned as First Minister, giving the SNP a fourth consecutive term. That’s an extraordinary achievement by anyone’s standards.

It’s hard cheese for her rivals. Richard Leonard is six months into his leadership of Scottish Labour but has made almost no impact. A massive 54% answered “don’t know” when asked how Leonard was doing, including 57% of those who voted Labour in 2017. Only 13% believed he was doing well. This suggests his sole tactic of tacking leftwards to attract disillusioned pro-indy socialists has backfired – where is his offer to Middle Scotland? Meanwhile, Ruth Davidson is personally popular, but her chances of catching the SNP at the 2021 election look slim.

I still find it hard to see the conditions under which a second indyref can take place before the next Holyrood election – other than SNP panic, which won’t be a good look. And even if Sturgeon felt, faced with the likely loss of that pro-independence majority, that she had no choice but to go for it, she would require Theresa May to give permission. That is almost certainly off the cards, so what then? A rogue poll? Is that how a new nation should be born? The further danger of going off half-cocked is that losing will set back the Yes movement for years. My instinct, which is shaped by conversations with those around the first minister, is that the SNP is moving on to a new phase of Scottish nationalism.

There is a growing acceptance that the best way to persuade the unpersuaded is to use the existing powers of Holyrood effectively – bring greater growth to the economy, improve schools’ performance, tackle the challenges facing our NHS. If you can show clear success on those fronts, the belief that independence could bring even more success becomes a conversation worth having.

The think tank I run, Reform Scotland, published a report last week by global small economies expert David Skilling that looked at how other similarly sized countries have made the best of what they have. There’s much to learn there.

The SNP needs to rediscover strategic patience to accompany its tactical nous. It should understand, as it used to, that the long game is worth it. I’m told that in recent days Finance Secretary Derek Mackay met the chief risk office of a major financial institution who told him the Growth Commission’s frankness had effectively “de-risked” the idea of Scottish independence for his company. The more these kinds of comments become common parlance, the less scary the leap might seem to voters.

One day The Economist might even have a cover that doesn’t question the price of Scottish independence, but makes the case for it.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe