Among modern prime ministers, Harold Wilson stands alone for having said no to America on a matter of war.

When Lyndon Johnson asked Wilson to join with the US as it escalated its invasion of Vietnam, the Labour leader decided against it.

Wilson’s boldness stands out in a historical context. When the US has taken military action, it has usually been able to count on having the UK at its side, for better or worse.

Our rulers have viewed Britain’s national interest best served by hugging our main international partner as closely as possible, for reasons ranging from power to principle, status to money.

Even Wilson would only go so far – when the left of his party asked why he refused to publicly criticise the Vietnam War, he is said to have explained, in industrial terms, the folly of attacking your creditors.

With the Iraq War facing massive opposition in the UK, George W Bush offered Tony Blair the opportunity to sit out the conflict. On principle and because he felt Britain’s long-term interests dictated going in, Blair made his fateful choice.

When Barack Obama wanted to mount military strikes in Syria, David Cameron gave his support but was defeated in parliament by a coalition of Tory refuseniks and left-wing Labour leader Ed Miliband.

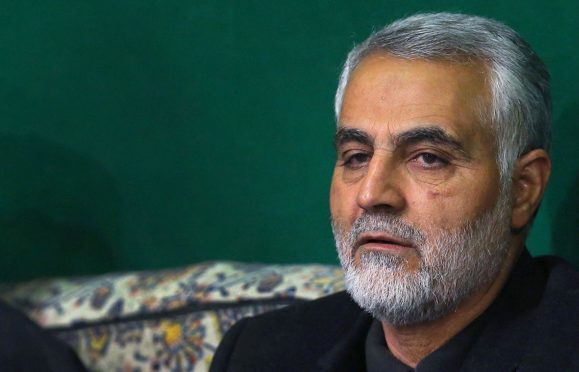

As we consider the aftermath of the US’s killing of General Soleimani, Iran’s most powerful military commander, our relationship with America once more becomes a subject for discussion.

The Iranians are likely to respond aggressively to the provocation of Soleimani’s death, in a region that is notoriously unstable – Ayatollah Khamenei has promised “harsh retaliation”.

The possibility of the West being dragged into another dangerous and unpredictable conflict in the year ahead is far from unthinkable.

In that event, what should Boris Johnson do in what could be the first test of Britain’s post-Brexit foreign policy posture?

He already has a close relationship with the US President Donald Trump.

After Brexit, the UK will no longer have the heft of European Union membership behind its international presence.

There are three power centres in the world – the US, the EU and China – and we belong to none of them. We will need more than ever to stay on side with the Americans, for economic reasons and to maintain what’s left of our global influence.

Britain still has one of the largest military capabilities in the world.

But Trump is a risky horse to back. It hardly seems coincidence that, as we enter a US election year, the President has licensed a high-profile and controversial military strike.

His judgements on foreign policy have been shaky in his first four years – Rex Tillerson, Trump’s former Secretary Of State, called him a “moron”. And war with Iran and its allies would likely make the Iraq quagmire resemble a picnic.

Trump is a narcissist and has shown time and again that he values loyalty above all other qualities. He is unlikely, as Bush did, to offer Johnson a free pass in the event of conflict.

Blair had “cojones”, Bush said when the Iraq decision was made.

Iran could quickly test what kind of man Boris Johnson is – and of what kind of country we now are.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe