WE will all have our reasons for remembering Christmas 2016, and hopefully they’ll be mostly good ones.

In 1916, though, it was a very different world.

The ongoing Great War had removed the chance of a proper happy Christmas for millions.

What happened in those dark days made Brexit, Donald Trump and any financial crisis look like a walk in the park by comparison.

That’s why this week, we’re looking back at how it was for Britain and abroad in December 1916 — and the comparisons with 2016 certainly show how much the world has changed!

Christmas 1916, as with every December 25 during the First World War, was a dangerous time of year for the British Government.

As the traditional ideas of seasonal cheer and celebration came up against the dark horrors of war, it could be very tricky for the politicians to balance things properly.

There were shortages, of course, such as sugar, bread, petrol and paper, and many of the ingredients required for traditional Christmas meals were almost impossible to source.

National morale, however, was obviously of great importance to those in power, and they did what they could to have some of these things more available than they were the rest of the year.

British mothers went to great lengths to come up with ingenious ways of making a Christmas dinner almost as good as the ones we’d enjoyed before the war.

For the children, many desired military-type gifts, toy guns, soldiers and little uniforms, but for the grown-ups it was all about giving gifts that were practical, not frivolous, in times of shortage.

Tools, safety razors, wallets, warm gloves, pipe sets, lighters and watches were all the rage, while the so-called Fuel of the British Army, cigarettes, were in high demand.

This desire for cigarettes was certainly chief among the memories of one man, non-smoker Alfred Anderson, from Scotland — who would one day become Scotland’s oldest man — in the Great War trenches.

Two Decembers previously, in 1914, he would recall how little gifts had arrived for the men from a special lady back home, and a spot of luck meant he could still enjoy part of the gift, if not the ciggies themselves.

The Princess Royal sent every man at the front a brass box, embossed with the profile of Princess Mary and filled with cigarettes.

It also contained a cream card, with 1914 on the front and the words: “With best wishes for a happy Christmas and a victorious New Year, from the Princess Mary and friends at home.”

Although he had no use for the cigarettes, Alfred’s treasured New Testament fitted the box snugly.

His mother had given it to him before he set off, inscribed: “September 5, 1914. Alfred Anderson. A Present from Mother.”

He would eventually get a serious so-called “Blighty wound” — hit in the neck — which would see him sent home.

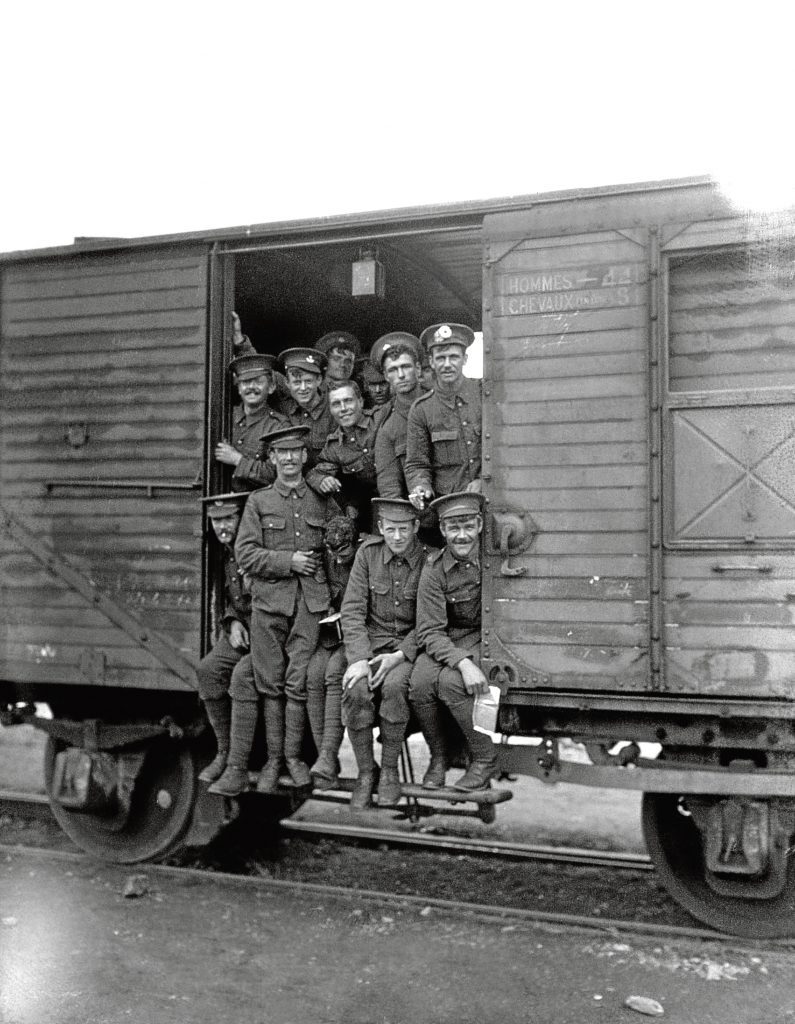

As so many men and women were away from home in the winter of 1916, the army postal service was extremely busy, and sent 114 million parcels from the UK, along with an incredible two billion letters over the course of the whole conflict.

The “Santa Clauses in khaki” got food, clothes, cigarettes and tobacco to the Front, and brought home priceless messages to say their lads were safe and looked forward to getting home.

Football, harmonicas, books and the occasional Christmas pudding — very, very gratefully received — were among the most-posted items.

Many lads, of course, were already home but stuck in a hospital ward through Christmas, so they were heartened to see the nurses do their best to decorate wards with baubles and ribbons and sing them some carols.

Back home, it certainly wasn’t all sweetness and light for civilians. Britain had been attacked from sea and air, and it was a terrifying time.

It could, of course, be greatly relieved by the unannounced appearance of their loved one at the front door.

The postal delays often meant a soldier was home before the letter arrived to inform his family.

The boys who did get leave were lucky — it was often decided by drawing lots, and wartime charities would take good care of them most of the way home.

Female volunteers served tea at railway stations to anyone in a uniform, while YMCA huts would provide shelter.

For those less fortunate when drawing lots, the same good-hearted people would do their best to put on small parties or celebrations.

Pantomimes, amazingly, continued through the conflict, albeit often adapted to cover what was going on in Continental Europe. Songs like It’s A Long Way To Tipperary and Keep The Home Fires Burning were mighty popular.

Audience members often remarked that the expensive scenery and positive, confident attitudes in the theatres was a real morale-booster, and they left convinced Britain was going to win the war.

The newspapers would still present their traditional Christmas issue, too, for similar reasons — they couldn’t be seen to be cutting back or feeling negative.

They often featured quite sentimental images, like robins in the trenches or handsome young soldiers looking optimistic and keen to join in the Christmas fun.

Britain also welcomed many foreign visitors — there were 250,000 Belgian refugees here in those days, with one popular magazine stating: “Over 1,000 toys have been personally distributed among the Belgian refugee children now being looked after in English homes and hostels.”

It’s quite strange to think that in 1916, there was no Bing Crosby singing White Christmas — and Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer wouldn’t make his first appearance until 1939, the year the Second World War began.

There were no video games or fancy trainers to be bought, either, although some papers featured adverts or stories about new-fangled gadgets that the better off might afford in Christmases to come.

Toasters, reading lamps and curling irons would be among the electrical goods that many would want at this time of the year, but in 1916 it wasn’t even common to have electric lights on the tree.

In fact, in the USA at this time, such lights would set you back a few dollars, the equivalent of $80 today, so certainly not a purchase to be made without thinking first!

Kodak’s early cameras were also capturing the imagination in the States, though few could afford them and almost nobody outside the professional world knew how to use them.

Adverts would often stress that taking photos was really very simple and anyone could do it — but even today, we’re sure it takes a bit of practice!

One thing far more of us did, however, was go to church.

Even in those darkest days, with loved ones in muddy, frozen trenches many miles away, soldiers and civilians remembered what December 25 marked.

Tragically, the most-horrific conflict the world had seen would stretch on for a couple more Christmases, but we would soon be able to celebrate it without worry and fear.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe