IT’S quite a trick to be super-suave but likeable at the same time — David Niven was the master!

London-born Niven made his first small appearance in a movie 85 years ago, and it was the start of a special career spanning over 50 years.

Although David would often claim to have been born in Kirriemuir, Angus, he came into the world at posh Belgravia, to posh parents, in 1910.

His father was of Scottish descent, but was killed at Gallipoli when the boy was just five — there have been claims the man his mother remarried was his real father and photos show a resemblance, but experts say that such things can often be misleading.

What we know for sure is that his dad, William, served in the Berkshire Yeomanry, and his grandfather had also been a soldier.

His mother, Henrietta, was of Welsh and French stock, and had a Lieutenant General for a grandfather. David Niven himself would become a Lieutenant Colonel in his own military career.

He would also, however, fall foul of the authorities many a time during his schooldays, due to his love of pranks.

He was expelled at the age of 10, a blow to his family as it stopped him going to Eton.

Niven would later go to Sandhurst’s Royal Military College, and said he would like to join any regiment except the Highland Light Infantry, as they wore tartan trews, not kilts!

He did, indeed, serve with the Highland Light Infantry and the Rifle Brigade, Prince Consort’s Own, but got bored with being in the Army during peacetime.

In fact, during a dull lecture on machine guns, when he was in a hurry to get away for a dinner date, he asked the speaker: “Could you tell me the time, sir? I have to catch a train.”

It was a line that could have come from one of his future films, and Niven was placed under close-arrest.

But he shared a bottle of whisky with the man guarding him and escaped out a window, heading for the US.

Resigning his commission by telegram, that Scotch must have still been on his mind, as David became a whisky salesman in America.

He wasn’t very good, despite his smooth patter.

As he tried to find a non-military role in life, the year 1932 marked his first, albeit brief, appearance in a movie, There Goes The Bride.

He didn’t even get a credit, with Jessie Matthews the star and Basil Radford another — some have described it witheringly as a mediocre screwball comedy, while others said it wasn’t actually too bad.

It was very good indeed for Niven, giving him a real taste of the cinema world.

But it was in 1934, at 24, that he arrived in Hollywood, a place that would come to appreciate his social skills far more than the Army.

Shortly, he starred in Barbary Coast, as a drunken sailor thrown out of a bar.

With critic Graham Greene describing it in glowing terms, it proved a very useful film to be in.

Mutiny On The Bounty the same year also got Niven noticed.

He got a much better role, though, in The Charge Of The Light Brigade in 1936, as Captain Randall, with Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland starring.

An unexpected result for Niven was getting the title for his future book, 1975’s Bring On The Empty Horses.

Featuring many tales of Hollywood, he got the title because it was what Light Brigade director Michael Curtiz would shout when he wanted riderless horses to come into shot.

By the late 30s, with the likes of 1938’s The Dawn Patrol, David was becoming a leading man, only for the war to throw everything into chaos.

When Britain declared war, he came home, once more joining the Army, despite the British Embassy advising actors not to.

He transferred into the Commandos, as the Rifle Brigade lacked excitement, and helped train them in Scotland.

He also took part in the Allied Invasion of Normandy, and would forge a friendship with Winston Churchill.

Winnie had singled him out, saying at a 1940 dinner party: “Young man, you did a fine thing to give up your film career to fight for your country.

“Mark you, had you not done so, it would have been despicable!”

David suffered tragedy when his first wife, Primula Susan Rollo, died after an accidental fall at a party in 1946, and in ’48, he experienced a career low, too, with the flop of Bonnie Prince Charlie with him in the lead role.

He had a strange time at the start of the 50s, going home to Britain to make movies that did well here but less so in America, and the opposite results with American films.

Otto Preminger, however, admired his acting in the Broadway stage run of Nina, and chose Niven for the film version of another play, The Moon Is Blue in 1953.

It would bring Niven a Golden Globe and heralded a gradual return to top form.

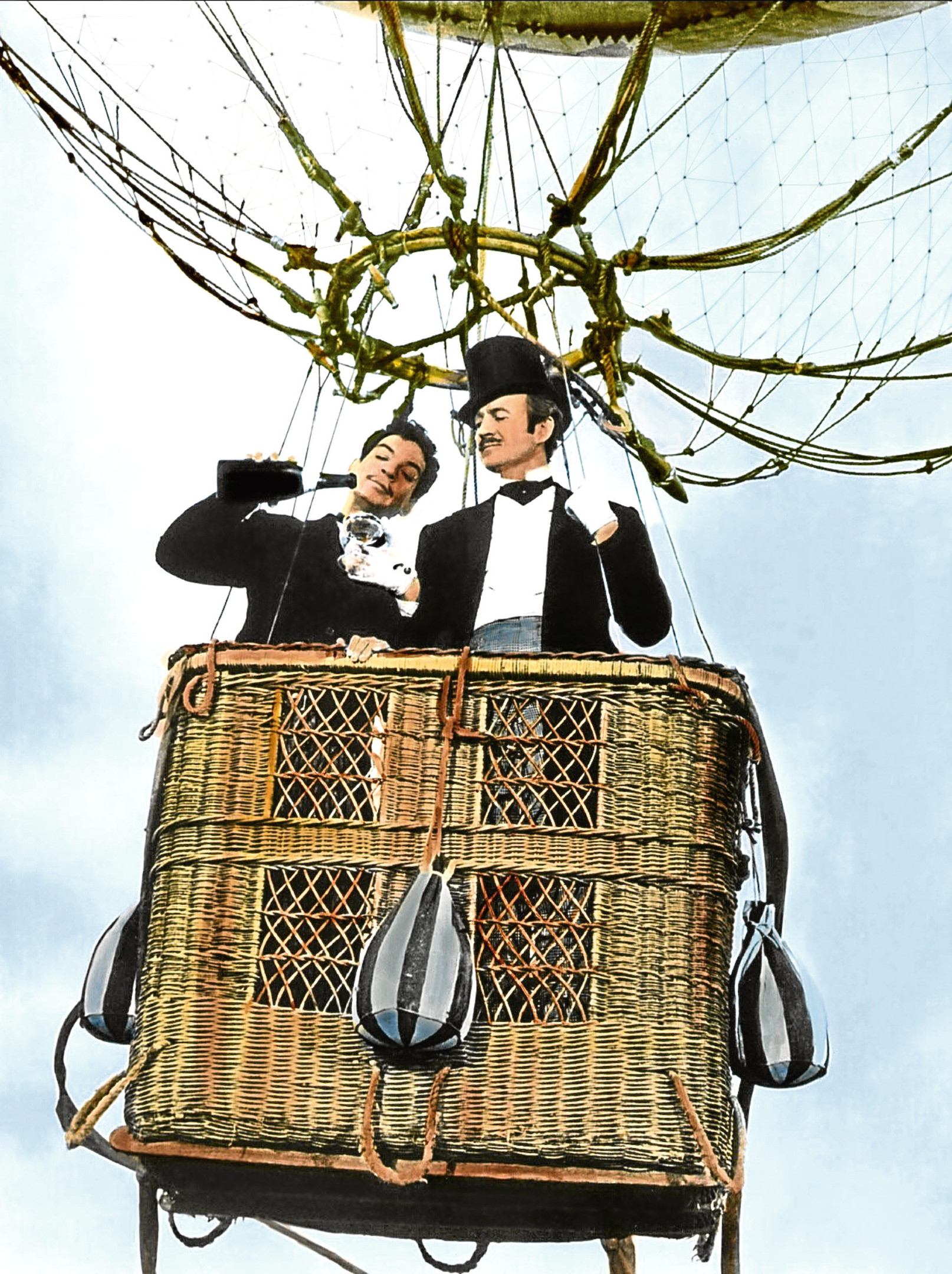

As Phileas Fogg in Around The World In 80 Days, a huge 1956 hit, he earned rave reviews, and the same year’s Separate Tables got him an Academy Award.

He was wonderful in 1960’s Please Don’t Eat The Daisies, and the new decade would be very kind.

Even The Guns Of Navarone, in ’61, and several more war or action flicks were eclipsed by 1963’s The Pink Panther.

Playing Sir Charles Lytton, Niven was sensational alongside Peter Sellers.

Niven’s own home life was great again, and he was married 35 years to his second wife, Sweden’s first supermodel Hjordis Paulina Genberg Tersmeden, until his death.

The story goes that she had shown up on the set of the ill-fated Bonnie Prince Charlie and refused to leave. Niven came over to eject her and promptly fell in love.

Niven had great versatility in his roles and his ability in comedies was also a strength of his.

Prudence And The Pill, from 1968, and The Brain — a French comedy from ’69 — did brisk box-office business and reminded people how funny he could be.

Death On The Nile, the 1978 blockbuster full of big names, saw him steal the show at times as Colonel Race, while his appearances in Trail Of The Pink Panther and Curse Of The Pink Panther were tinged with sadness.

Peter Sellers, in fact, had died a year and a half before work began on Trail, and his parts were cobbled together from deleted scenes.

David Niven was in the early stages of motor neurone disease, and his voice had to be overdubbed by impressionist Rich Little.

Sadly, by the summer of 1983, just weeks before Curse was released, the illness killed him. Cinema had lost a true British great.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe